059

CHAPTER 7

Polio Infantile Paralysis

HOW TO RECOGNIZE PARALYSIS CAUSED BY POLIO

| Intelligence and the mind are not affected. |

| Feeling is not affected. |

| 'Knee jerks' and other tendon reflexes in the affected

limb are reduced or absent. (In cerebral palsy, 'knee jerks' often

jump more than normal. See Page 88.)

Also, the paralysis of polio is 'floppy'; limbs affected by cerebral

palsy often are tense and resist when straightened or bent (see

Page 102). |

|

|

| The paralysis does not get worse with time. However, secondary

problems like contractures, curve of the backbone and dislocations may

occur.

|

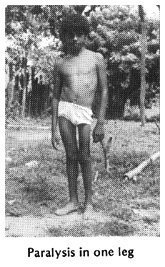

| Of children who become paralyzed by polio: |

30%

recover completely in the first weeks or months. 30%

recover completely in the first weeks or months. |

30%

have mild paralysis. 30%

have mild paralysis. |

30%

have moderate or severe paralysis. 30%

have moderate or severe paralysis. |

10% die (often because of difficulty breathing or swallowing). |

060

BASIC QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS ABOUT POLIO

How common is it? In many countries, polio - or

'poliomyelitis'- is still the most common cause of physical disability in

children. In some areas, at least one of every 100 children may have some

paralysis from polio. Where vaccination programs are effective, polio has

been greatly reduced.

What causes it?A virus (infection). The

infection attacks parts of the spinal cord, where it damages only the

nerves that control movement. In areas with poor hygiene and lack of

latrines, the polio infection spreads when the stool (shit) of a sick

child reaches the mouth of a healthy child. Where sanitation is better,

polio spreads mostly through coughing and sneezing.

Do all children who become infected with the polio virus become

paralyzed? No, only a small percentage become paralyzed. Most

only get what looks like a bad cold, with fever. However, if a child with

a 'cold' caused by the polio virus is given an injection of any

medication, the irritation caused by the injection can

bring on paralysis. (See warning on Page

19.)

Is the paralysis contagious? No, not after 2 weeks

from when a child first gets sick with polio. In fact, most polio is

spread through the stool of non-paralyzed

children who have 'only a cold' caused by the polio virus.

At what age do children get polio? In areas with poor

sanitation, polio most often attacks babies from 8 to 24 months

old, but occasionally children up to age 4 or 5. As sanitation improves,

polio tends to strike older children and even young adults.

Who does it most often affect? Boys, a little more

than girls. Unvaccinated children much more often than vaccinated

children. (See Page 74). Young children who are given

injections unnecessarily are paralyzed by polio more often those who are

not.

How does the paralysis begin? It begins after signs of

a cold and fever, sometimes with diarrhea or vomiting. After a few days

the neck becomes stiff and painful and parts of the body become limp.

Parents may notice the weakness right away, or only after the child

recovers from the acute illness.

Once a child is paralyzed, what changes or improvements can be

expected? Often the paralysis will gradually go away, partly or

completely. Any paralysis left after 7 months is usually permanent. The

paralysis will not get worse. However, certain secondary problems may

develop-especially if precautions are not taken to prevent them.

What are the child's chances of leading a happy, productive

life? Usually very good-provided the child is encouraged to do

things for himself, to get the most out of school, and to learn useful

skills within his physical limitations (see Page

497).

Can persons with polio marry and have normal children?

Yes. Polio is not inherited (familial) and does not affect ability to have

children.

061

SECONDARY PROBLEMS TO LOOK FOR WITH POLIO

By secondary problems, we mean further disabilities or

complications that can appear after, and because of, the original

disability.

CONTRACTURES OF JOINTS

| A contracture is a shortening of muscles and tendons

(cords) so that the full range of limb movement is prevented. Unless

preventive steps are taken, joint contractures will form in many

paralyzed children. Once formed, often they must be corrected before

braces can be fitted and walking is possible. Correction of advanced

contractures, whether through exercises, casts, or surgery (or a

combination), is costly, takes time and causes discomfort. Therefore

early prevention of contractures is very important.

A full discussion of contractures, their causes, prevention, and

treatment is in the next chapter (Chapter

8). Methods and aids for correcting contractures are described in

Chapter 59. |

| TYPICAL CONTRACTURES IN POLIO

A child with paralysis who crawls

around like this rid never straightens her legs will gradually develop

contractures so that her hips, knees, and ankles can no longer be

straightened.

|

|

OTHER COMMON DEFORMITIES

Weight bearing (supporting the body's weight) on weak joints can cause

deformities, Including:

| OVER-STRETCHED

JOINTS |

DISLOCATIONS

|

|

WARNING:

Dislocations like these are sometimes caused by

stretching contractures incorrectly. (See

Page 28.) |

|

SPINAL

CURVE SPINAL

CURVE

Minor curve of spine can be caused by tilted hips, as

a result of a short leg.

More serious curve of the spine is caused by muscle weakness of the

back or body muscles. The curve can become so severe that it endangers

life by leaving too little room for the lungs and heart. |

At

first, the spinal curve straightens when the child is positioned

better. But in time the curve becomes more fixed (will not straighten

any more). For information on spinal curves, see

Chapter 20. At

first, the spinal curve straightens when the child is positioned

better. But in time the curve becomes more fixed (will not straighten

any more). For information on spinal curves, see

Chapter 20. |

062

WHAT OTHER DISABILITIES CAN BE CONFUSED WITH POLIO?

| Sometimes cerebral palsy can be mistaken for

polio-especially cerebral palsy of the 'floppy' type. |

| However, cerebral palsy

usually affects the body in typical patterns:

|

Polio has a more

irregular pattern of paralysis.  |

In cerebral palsy, usually you can find other signs of brain damage:

over-active knee jerks and abnormal reflexes (see

Page 88), developmental delay, awkward or uncontrolled movement, or

at least some muscle tenseness (spasticity).

| In muscular dystrophy, paralysis begins little by

little and steadily gets worse (see Page 109). |

| Hip problems (see Page 155)

can cause limping, and muscles may become thin and weak. Check hips for

pain or dislocations. (Note: Dislocated hip may also occur secondary to

polio.) |

| Note: Polio can occur before or after a child

has any of these other problems. Check carefully. |

| 'Erb's palsy', or partial paralysis in one arm and

hand, comes from birth injury to the shoulder (see

Page 127). |

| Leprosy. Foot and hand paralysis begins gradually

in older child. Often there are skin patches and loss of feeling (see

Page 215). |

| Spina bifida is present from birth. There is

reduced feeling in the feet, and often a lump (or scar from surgery) on

the back (see Page 167). |

| ALWAYS EXAMINE THE BACK IN A CHILD WITH PARALYSIS OF THE LEGS, AND

CHECK FOR FEELING. |

| Injuries to the spinal cord (see

Page 175) or to particular nerves going to the arms or legs. There

is usually a history of a severe back or neck injury, and loss of

feeling in the paralyzed part. |

| Tuberculosis of the spine can cause gradual or

suddenly increasing paralysis of the lower body. Look for typical bump

on spine (see Page 165).

|

| Other causes of paralysis or muscle weakness. There

are many causes of floppy paralysis similar to polio. One of the most

common is 'Guillain-Barre' paralysis. This can result

from a virus infection, from poisoning, or from unknown causes. It

usually begins without warning in the legs, and may spread within a few

days to paralyze the whole body. Sometimes feeling is also reduced.

Usually strength slowly returns, partly or completely, in several weeks

or months. Rehabilitation and prevention of secondary problems

are basically the same as for polio. |

063

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

DURING THE ORIGINAL ILLNESS, when the child first

becomes paralyzed:

| No medicines help, either during the first

illness, or later. |

| Rest is important. Avoid forceful exercise

because this may increase paralysis. Avoid injections. |

| Good food during recovery helps the child become

stronger. (But take care that the child does not eat too much and get

fat. An overweight child will have more problems with walking and

other movements.) For suggestions about good food, see

Where There Is No Doctor,

Chapter 11. |

| Position the child to be comfortable and to avoid

contractures. At first the muscles will be painful, and the child will

not want to straighten his joints. Slowly and gently try to straighten

his arms and legs so that the child lies in asgood a position as

possible. (See Chapter 8.) |

| GOOD POSITION

Arms, hips, and legs as straight as possible. Feet supported. |

BAD POSITION

Bent arms, hips, and legs. Feet in tiptoe position. |

Note: To reduce pain, you may need to put

cushions under the knees, but try to keep the knees as straight as you

can.

FOLLOWING THE ORIGINAL ILLNESS:

| Continue with good food and good

positions. |

| As soon as the fever drops, start exercises to

prevent contractures and return strength. Range-of-motion

exercises are described in

Chapter 42. Whenever possible, make exercises fun. Active

games, swimming, and other activities to keep limbs

moving as much as they can are important throughout the

child's rehabilitation. |

|

Crutches, leg braces(calipers), and other

aids may help the child to move better and may prevent contractures or

deformities. |

| In special cases, surgery may be needed to

correct contractures, or to change the place where strong muscles

attach, so that they help do the work of weak ones. When a foot is

very floppy or bends to one side, surgery to join certain bones of the

foot may help. But because bone surgery stops the growth of the foot,

usually it should not be done before age 12 or 13. |

| Encourage the child to use his body and mind as

much as possible, to play actively with other children, to

take care of his daily needs, to help with work,

and to go to school. As much as possible,

treat him like any other child. |

064

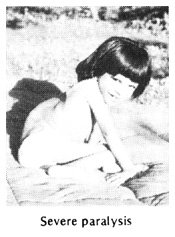

REHABILITATION OF THE CHILD WITH PARALYSIS

All children paralyzed by polio can be helped by certain basic

rehabilitation measures-such as exercise to keep a full range of motion

in the affected limbs.

However, each child will have a different combination and

severity of paralyzed muscles, and therefore will have his own special

needs.

For some children, normal exercise and play may be all that are

needed. Others may require special exercises and playthings. Still

others may need braces or other aids to help them move about better, do

things more easily, or keep their bodies in healthier, more useful

positions. Those who are severely paralyzed may be helped most by a

wheelboard (trolley) or wheelchair.

Every child needs to be carefully examined and evaluated in

order to best meet his or her particular needs. The earlier you evaluate

a child's needs, and take steps to meet them, the better.

Unfortunately, 'in most areas where polio is still common, village

rehabilitation programs do not exist or are just beginning. Many

children (and adults) who have been paralyzed for a long time already

have severe deformities or joint contractures. Often these must be

corrected before a child can use braces or begin to walk.

Because contractures are such a common problem, not only with polio

but with many other disabilities, we discuss them separately in the next

chapter. Before evaluating a child with polio, we strongly

suggest you read Chapter 8 on

contractures.

| WARNING: Before deciding on any aid or

procedure, carefully consider its advantages and disadvantages. For

example, some deformities may be best left uncorrected because they

actually help the paralyzed child stand straighter or walk better (see

Page 530). And some aids or braces may prevent a child from

developing strength to walk without aids (see

Page 526).Before deciding what aid or procedure to use,

we suggest you read Chapter 56,

"Making Sure Aids and Procedures Do More Good Than Harm." |

065

PROGRESS OF A CHILD WITH POLIO:

THE CHANGING NEEDS FOR AIDS AND ASSISTANCE

1. exercises to keep full range of motion, starting

within days after paralysis appears and continuing throughout

rehabilitation

2. supported sitting in positions that help prevent

contractures

3. active exercises with limbs supported, to gain

strength and maintain full motion

4. exercise in water - walking, floating, and swimming, with

the weight of the limbs supported by the water

5. wheelboard or wheelchair with supports to prevent

or correct early contractures.

Note: These also provide good arm exercise

in preparation for walking with crutches.

6. braces to prevent contractures and prepare for

walking

7. parallel bars for beginning to balance and walk

8. walking machine or 'walker'

9. crutches modified as walker for balance and extra

support

10. under arm crutches

11 . forearm crutches and perhaps in time . . .

12. a cane or no arm supports at all

Note: These pictures are only an example -

but most of the steps are necessary for many children. Children who

begin rehabilitation late may also have contractures or deformities

requiring corrective steps not shown here.

066

EVALUATING A CHILD'S NEEDS FOR AIDS AND PROCEDURES

Step 1: Start by learning what you can through

talking with the child and family (see Child's History,

Page 37 to 38). As you do this,

watch the child move about. Observe carefully which parts of

the body seem strong, and which seem weak. Look for any differences

between one side of the body and the other-such as differences in the

length or thickness of the legs. Are there any obvious deformities, or

joints that do not seem to straighten all the way? If the child walks,

what is unusual about the way she does it? Does she dip forward or to

one side? Does she help support one leg with her hand? Is one hip lower

than the other? Or one shoulder? Does she have a humpback, a swayback,

or a sideways curve of the back?

These early observations will help you know what parts of the body

you most need to check for strength and range of motion. Often, by

watching a child you can begin to get an idea about what kind of aids or

assistance may help. For example:

Carmen appears to have severe paralysis affecting both legs and

her right arm. Weakness in her trunk (main part of the body) appears

to have caused a severe S-shaped curve of the spine. |

She will probably never walk, and will need a wheelchair or

wheelboard.

You may want also to make her a body brace, or help her in other

ways to sit more upright and try to keep the spine from bending

more. |

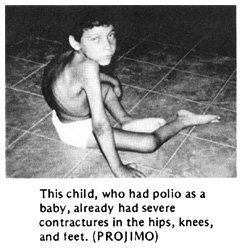

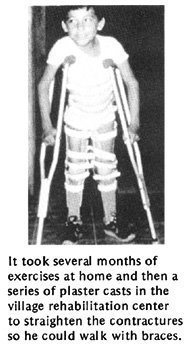

Pedro appears to have severe paralysis in his legs and hips. It

looks as if his hips, knees, and feet cannot straighten

(contractures). Weak stomach muscles and severe hip contractures may

be the cause of his swayback.

Because his arms look strong, Pedro will probably be able to walk

with crutches and leg braces. But first his contractures must be

straightened.

If the contractures cannot be straightened by gradual stretching,

he may need surgery. |

067

Manuel walks with the help of a stick. He appears to have

paralysis mainly in his right leg and foot. Because of weak thigh

muscles, he 'locks' his knee backward in order to bear weight on

it. This 'back-kneeing' has become more and more extreme as the

cords behind the knee stretch. The foot is very unstable and flops

to one side. The weaker leg looks somewhat shorter-and for walking

is much shorter because of the bent-back knee and bent-over foot.

He might be able to walk without the stick if he uses a

below-knee brace to stabilize his foot. (See

Page 550.)

But the back-knee would become worse and worse until he could

not walk. So probably he should have a long-leg brace. The brace

might allow his knee to bend backward just a little for stability

- so that no knee lock is needed. |

Afia leans forward and pushes her weak left thigh with her

hand when she walks. Her left knee cannot quite straighten. Her

weak leg looks a little shorter than the other.

Exercises to get her knee straighter or so it can bend very

slightly backward may be all that is needed for Afia to walk

without using her hand.

Or she may need an above-knee brace with a strap to pull the

knee back.

Or she may only need a below-knee brace that helps push her

knee back.

The brace bends the foot down just a little, so that by

bearing weight on toes (rather than heel) her knee is pushed

back.

To get a better idea about which of the three solutions may

work best for Afia, you will need to do a careful physical

examination, testing range of motion and muscle strength of the

hip, knee, and ankle joints. |

Step. 2: This is the physical

examination. It should usually include:

1.Range-of-motion testing, especially where

you think there might be contractures. (See "Physical

Examination," Page 27 to 29, and

"Contractures," Page 79 and

80.)

2. Muscle testing, especially of muscles

that you think may be weak. Also test muscles that need to be

strong to make up for weak ones (such as arm and shoulder

strength for crutch use). (See Page 27

and Page 30 to 33.)

3. Check for deformities: contractures;

dislocations (hip, knee, foot, shoulder, elbow); difference in

leg length; tilt of hips; and curve or abnormal shape of the

back. (See Page 34.)

068

Step 3: After the physical exam,

again observe how the child moves or walks. Try to

relate her particular way of moving and walking with

your physical findings (such as weakness of certain

muscles, contractures, and leg length). (For an example,

see Page 70.)

Step 4: Based on your observations and

tests, try to figure out what kind of exercises, aids,

or assistance might help the child most. Consider the

advantages of different possibilities: benefit, cost, comfort,

appearance, availability of materials, and whether the child is

likely to use the aid you make. Ask the child and parents for

their opinions and suggestions.

Step 5: Before making a final brace or aid

to fit the child, if possible test to see how well it

may work by using a temporary aid or old brace from

another child. For example,

If a child's ankle bends over to the outside like this... |

...a lift on the outer side of the sole like this, may

help to keep the foot straighter. |

But before nailing and glueing in the lift, quickly make

a trial one of cardboard or something else and fasten it

temporarily to the sandal or shoe with tape or string. Then

have the child walk.

Note: For a few children, a

lift like this will help. For many it will not. |

| Ask the child what she thinks.

|

Step 6: After the child, her parents, and

you have decided what kind of brace or aid might work best,

take the necessary measurements and make the brace or

aid. When making it, once again it is wise to put it

together temporarily so that you can make adjustments before

you rivet, glue, or nail it into its final form. (See

Page 540.)

Step 7: Have the child try the

brace or aid for a few days to get used to it and to

see how well it works. Ask the child and parents if it seems

to help. Does it hurt? Are there any problems? How could it be

improved? Is there something that might work better? Make what

adjustments are necessary. But remember that no brace or aid

is likely to meet the needs of a child perfectly. Do the best

you can.

069

Here is a story of how workers in a small village

rehabilitation program figured out what kind of aids a child

needed. How many of the steps we have just discussed

did they follow? Was each step important?

A STORY: A BRACE FOR SAUL

One day a mother from a neighboring village arrived at the

village center with her 6 year old son, Saul. Mari and Chelo,

2 of the village rehabilitation workers, welcomed them warmly.

Learning that Saul had polio as a baby, they asked him to

walk, and then to run, while they watched carefully. Saul

limped a lot and one leg looked thinner and shorter. With each

step it bent back at the knee.

"He walks quite well, really," said Mari. "But he has to

'lock' his knee back in order to put weight on it. That knee

is going to keep stretching back and some day it will give

out."

"A long-leg brace would protect his knee," suggested Chelo.

"Oh, please, no!" said Saul's mother. "A year ago we took

Saul to the city and the doctors had a big metal brace made

for him. It cost so much we are still in debt! Saul hated it!

He would always take it off and hide it. We tried and tried to

get him to use it, but he wouldn't."

"That's not surprising," said Mari. "Often a child who can

walk without a brace will refuse to use one-even if he walks

better with it. We could make him a long-leg brace out of

plastic. It would be much lighter. What do you say, Saul?"

Saul began to cry.

"Don't worry, Saul. Maybe we can do something simpler,"

said Mari. "But first let's examine you, okay?" Saul nodded.

On muscle testing Saul, they found he could not straighten

his knee at all. But he had fair strength for bending his knee

back

and his hip forward,

and good strength for bending his hip back.

070

"With the hip and thigh strength he has, he should almost

be able to stand on that leg without the knee bending back,"

said Mari. "Saul, let's see you try it like this. Pretend

you're a stork!" For a moment Saul could do it. "Good!" said

Mari. "Every day stand like that and see how high you can

count without letting your knee go back. Every day try to beat

your old record! Okay?"

"Okay," said Saul. Sounds like fun!"

"The stork exercises may help," said Chelo. "But I still

think he needs a brace. At least at first."

We must weigh the advantages against the disadvantages,"

said Mari. "A long-leg brace would keep his knee straight. But

it could weaken the muscles he needs to strengthen. Since the

brace would keep his leg from bending back, he wouldn't have

to use his muscles to do it.

"On the other hand, we might try a short-leg brace that

holds his foot at almost a right angle. Then, to step flat he

will have to keep his knee nearly straight. It could help him

strengthen his behind-the-thigh muscles."

"Let's try it!" Everyone agreed, except Saul.

Chelo brought someone's old, lower-leg plastic brace and

showed it to Saul. "See how it will fit right around your leg.

It isn't heavy at all. Lift it! And no metal joints to get in

the way! What do you say? Do you want to try it?"

"I guess so," said Saul.

When the brace was made, they tested it. Saul said he liked

it. At first, when he tried hard, he could walk without

bending his knee back. But after a few days, his mother

complained that often he would walk, or even stand, with his

knee bent way back as before, and his toes in the air, like

this.

"I have an idea," said Chelo. "Why don't we let the heel

stick out behind the shoe. That way, when he steps, his weight

will come well forward of the back of his heel. This should

help bring his foot down and his knee forward."

They tried it, and most of the time (especially when he was

reminded) Saul walked without letting his knee bend back

much."

At home Saul's mother encouraged him to do his stork

exercises. As his muscles grew stronger, he began to walk

without bending his knee far back-even in active play!

071

WILL MY CHILD EVER BE ABLE TO WALK? "

This is often one of the first questions asked by the

parents of a disabled child. It is an important question.

However, we must help parents realize that other things in

life can be more important than walking (see

Page 93).

If the child whose legs are severely paralyzed by polio is

to walk, generally she will need at least 2 things:

1. fairly strong shoulders and arms for

crutch use

2. fairly straight legs (hips, knees, and

feet). (it is important to correct contractures so that the

legs are straight or nearly straight before trying to adapt

braces for walking.)

To evaluate a child's possibility for walking, always

test arm and shoulder strength:

Have her try to lift her body weight off the ground with

her arms, like this.

If she can easily lift up and down several times, she has a

GOOD chance of being able to walk using crutches.

If her arms and shoulders are so weak she cannot begin to

lift herself, her chances for crutch - walking are POOR.

If her shoulder and arm strength is FAIR, and the child can

almost lift herself, daily exercise lifting her weight like

this may increase strength enough to make crutch use possible.

Having the child lift herself while holding bar like this

will also help strengthen her hands and wrists for crutch use.

Pushing herself in a wheelchair or wheelboard (trolley) is

a practical way to strengthen shoulders, arms, and hands.

If the child cannot lift herself because of weak elbows,

put simple splints on her arms to see if she can lift herself

with these.

If she can lift herself with the elbow splints, maybe she

can use crutches that give elbow support.

If she is fat, she should lose weight.

This will make walking on weak limbs much easier.

Now check how straight the legs will go. (See

range-of-motion testing, Page 27.)

If the hips, knees, and feet can be placed in fairly

straight positions, chances for walking soon with braces are

good (if arm strength is good).

But if the child has much contracture of the hips, knees,

or feet, these will need to be straightened before she will be

able to walk.

For correction of contractures, see

Chapters 8 and

59.

Sometimes, if contractures are severe in one leg only, the

child can learn to walk on the other leg only, with crutches.

But it is best with both legs, whenever possible.

072

After checking arm strength and leg straightness, the next

thing to check is the strength in the ankles, knees,

and hips. This will help you decide if the child

needs braces, and what kind.

A child with a foot that hangs down (foot

drop), or flops to one side may be helped by

a below-knee brace of plastic or metal.

For foot drop, you can make a brace that lifts the foot

with a spring or rubber band. (See

Page 545.)

The kind of brace you choose will depend on various

factors, including cost, available skills and materials, and

what seems to work best for the particular child.

Advantages and disadvantages of different kinds of braces, and

how to make them, are discussed in

Chapter 58.

A child with a weak knee may need a

long-leg brace of plastic or metal.

Note:Not all children with no strength to

straighten the knee need long-leg braces:A child with

strong butt muscles may be able to walk without a brace.

If a child has a contracture and cannot walk with his

knee straight, correcting the contracture until his knee

bends very slightly backward may allow him to walk better. |

CAUTION: A stiff foot with a

moderate tiptoe contracture may help push the knee back,

just like a stiff brace. Correcting the contracture may

make walking more difficult or impossible, so that a brace

is needed where none was needed before. (See

Chapter 56.) |

073

A child with very weak hip muscles may

find his leg flops or twists about too much with a long-leg

brace.

He may need a brace with a hip band to help stabilize the

leg at the hip.

A child with weak body and back muscles,

who cannot hold up her body well, may need long-leg braces

attached to a body brace or body jacket.

Note: Often a child at first may

need a hip band or body jacket to help stabilize her for

walking. A few weeks or months later she may no longer need

it. Removing it may help the child gain more strength and

control. It is important to re-evaluate the child's

needs for bracing periodically.

| Take care to use no more bracing than is

needed. |

A child whose backbone is becoming seriously curved

may benefit from a body brace (or in severe cases, she may

need surgery).

If necessary, the body brace can be attached to long-leg

braces as shown above.

More information on spinal curve can be found in

Chapter 20. For

information on how to make body braces and jackets, see

Chapter 58.

074

PREVENTION OF POLIO

POLIO VACCINE, the best protection - IF it has been

kept cold continuously! |

| Vaccinate babies with polio vaccine. Be

sure they get the vaccine 3 times by the time they are 8

months old. It is usually best to give the first polio

vaccination around 3 months of age. |

| Vaccinate as many children as possible.

The vaccine given by mouth is alive. So, if most of the

children are vaccinated, the live vaccine will spread to

children who have not been vaccinated, and protect them

also. |

| Try to Keep the live polio vaccine frozen

until shortly before it is used. For up to 3 months it can

be thawed and refrozen. But it must be kept cold or it will

spoil. |

| Seek community help with vaccination

and in keeping vaccine cold. Sometimes vaccines do not reach

villages because health posts lack refrigeration. But often

store-keepers and a few families have refrigerators. Win

their interest and cooperation. |

| To give best protection, vaccinate the child

when she does not have a fever or a cold or diarrhea.

But if by 6 months of age, the child still has not been

vaccinated, give her the polio vaccine even if she is a

little sick. However, there is a chance that the vaccine may

not work if it is given when the child is sick (with a virus

infection). Therefore, still try to give the complete series

of 3 vaccinations and one booster later, when the child is

not sick. |

It is estimated that in poor countries at least

one-third of vaccines are spoiled by the time they reach the

children. Therefore, even in children who

have been vaccinated, additional precautions are needed:

| Breast feed your baby as long as

possible. Breast milk contains 'antibodies' that may help

protect against polio. (Babies rarely get polio before 8

months old because they still have their mothers'

antibodies. Breast feeding may make this protection last

longer.) |

| Do not give injections of any medicine to babies

or children, except when absolutely necessary.

Irritation caused by injected medicine can turn a mild,

undiagnosed polio infection into paralysis. It is estimated

that today 1 out of 3 cases of paralysis from polio is

brought on by injections (see Page

19). |

| Organize the people and help out in

popular campaigns to encourage vaccination, breast

feeding, and limited, sensible use of

injections. Community theater and puppet

shows are good ways to raise awareness on these

issues. See Chapter 48. |

075

PREVENTION of secondary problems

We have already discussed some ways to prevent new problems

or complications in a child with paralysis. In summary,

important measures include:

| Prevent contractures and deformities.

Begin appropriate range-of-motion exercises

as soon as the paralysis appears. |

| At the first sign of a joint contracture, do

stretching exercises 2 or 3 times a day- every day. |

| Stretching exercises work better if you

stretch the joint firmly and continuously for a few

moments,

|

instead of 'pumping' the limb back and

forth.

We emphasize this point because in many countries

parents are taught the pumping method - which does very

little good.

|

For more details, see "Contractures,"

Chapter 8.

| Evaluate the child's needs regularly,

and change or adapt aids, braces, and exercises to

meet her changing needs. Too little or too much

bracing can hold the child back or create new problems. |

| Be sure crutches do not press hard under the

arms; this can cause paralysis of the hands (see

Page 393). |

| Try not to let the child's physical disability

hold back her overall physical, mental, and social

development. Provide opportunities for her to lead

an active life and take part in games, activities, school,

and work with other children.

PART 2 of this book

discusses ways to help the community meet the needs of

disabled children. |

OTHER PARTS OF THIS BOOK THAT MAY BE USEFUL

IN MEETING NEEDS OF A CHILD AFFECTED BY POLIO

* Especially important chapters are marked with a star:*

Physical examination,

Chapter 4

Measurement of contractures and progress,

Chapter 5

* Contractures, Chapter

8

Dislocated hips,

Chapter 18

Spinal curve, Chapter

20

* Range-of-motion and other exercises,

Chapter 42

Crutch use, wheelchair transfers, etc.,

Chapter 43

Community needs, social adjustment, growing up,

PART 2, especially

Chapters 47,

48,

52,

53

Making sure aids and procedures meet the child's needs,

Chapter 56

* Braces and calipers,

Chapter 58

* Correcting contractures,

Chapter 59

Correcting club feet,

Chapter 60

Special seating and wheelchairs, Chapters

64,

65,

66

* Aids for walking,

Chapter 63

For more information on polio, see References

Page 637.

|

076

A BOY WITH POLIO BECOMES AN OUTSTANDING

HEALTH AND REHABILITATION WORKER

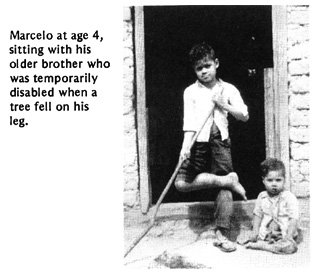

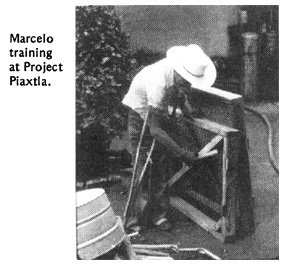

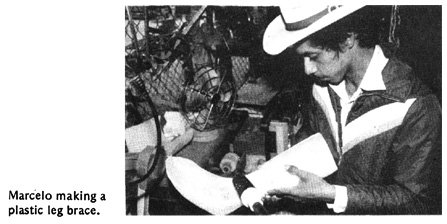

Marcelo Acevedo was disabled by polio. He and his

family lived in a village 2 days from the closest road.

Village health workers from Project Piaxtla helped Marcelo

get surgery for his knee contractures. After surgery he

got braces and went to school. Then they trained him as a

village health worker, and he returned to serve his

village.

When PROJIMO was formed, Marcelo joined as a village

rehabilitation worker. He studied brace-making as an

apprentice in 2 brace shops in Mexico City.

Marcelo is now one of the leaders in PROJIMO, and has

gained the respect of the whole village. He has recently

married a village woman.

|