PART 3

WORKING IN THE SHOP

Rehabilitation Aids

and Procedures

CHAPTER 56

INTRODUCTION TO PART 3

Making Sure Aids and Procedures

Do More Good than Harm

When I (David Werner) was about 10 years old, I was taken to a doctor because I was having problems with my feet. I kept falling over things and spraining my ankles. No one knew yet that these were early signs of a progressive muscular atrophy.

The doctor examined my feet. They were somewhat weak and floppy, so he prescribed arch supports. An 'orthotist' across town would make them.

When the arch supports were ready, the orthotist put them on my feet. "Do they hurt?" he asked. "No," I said. So I was sent home with instructions to wear them every day.

I hated the things! - not because they hurt, but because it was harder for me to walk with them than without them. They pushed up on my arches and bent my ankles outward. I fell and sprained my ankles more than ever.

I tried to protest, but nobody listened to me. After all, I was only a child. "You have to get used to them!'' I was told. "Who do you think knows best-you or the doctor?"

So mostly I suffered in silence. I took the arch supports out of my shoes and hid them whenever I could. But when I was caught I was punished. I was made to feel naughty and guilty for not doing what was 'best' for me.

Several years later, as my walking continued to get worse, I was prescribed a pair of metal braces. They held my ankles firmly, but they were heavy, uncomfortable, and made me feel more awkward than ever. I hated them, but wore them because I was told to.

One holiday I took a long walk in the mountains. The braces rubbed the skin on the front of my legs so badly that deep, painful sores developed. I refused to wear them again.

It was not until many years later, long after I had begun to work with disabled children, that a brace maker and I figured out what kind of ankle support would best meet my needs. So now I use lightweight, plastic braces that provide both the flexibility and support that best suit me.

When I look back, I realize that the doctor did not know more about what I needed than I knew. After all, I was the one who lived with my feet! True, at age 10, I could not explain the mechanics and anatomy for what was happening. But I did have a sense of what helped me manage better and what did not. Maybe if the adults who were so eager to help had included me in deciding what I needed, I might have had aids that better met my needs. And I might not have felt so guilty and naughty for expressing my opinion.

I learned something from these childhood experiences. I learned how important it is to listen to the disabled child, to ask the child at every stage how she feels about an aid or an exercise, and to include the child and her parents in deciding what she needs. The child and her parents may not always be right. But doctors, therapists, and rehabilitation workers are not always right either. By respecting each other's special knowledge and looking together for solutions, they can come closest to meeting the child's needs.

| Some of the best design improvements in aids and equipment come from the ideas and suggestions of the children who try them out. |

PRECAUTIONS IN PROVIDING A CHILD WITH AIDS, EQUIPMENT, AND PROCEDURES

To make sure aids and equipment really meet the child's needs, consider the following:

1.How necessary are the aids or equipment? Might it help the child more to learn to manage without them? For example:

| Elena has arthritis. Her thighs have become too weak to

support her body weight. You can fit her with braces and

crutches. But watch out! These aids will not make her thighs

stronger. They may even make them weaker, since she could then

walk without having to use her thigh muscles.

|

| A better solution might be exercise to strengthen her

thighs. For example, walking in water will make it easier for

her legs to support her weight.

|

| Also, using a cane instead of crutches helps her to use and strengthen her thigh muscles (see Page 587). |

| AVOID MAKING THE CHILD TOO DEPENDENT ON AIDS! |

![]()

2. As any child grows and develops, his needs keep changing.Frequent re-evaluation is necessary to find out if an aid should be changed or is no longer needed. Ask the child what he wants. For example:

| Misha has been slow to develop balance for sitting. At

first, straps helped him sit in a stable, upright position.

APPROPRIATE ONLY AT FIRST |

| But as he continues to develop, keeping him strapped in a

chair may keep him from improving his balance more or from

learning to sit without help.

APPROPRIATE LATER |

| Misha might be helped more by a seat that gives support to his legs and hips but lets him balance the top part of his body without help (see Page 573). |

![]()

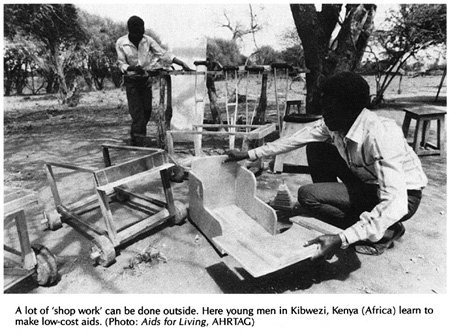

3. A simple, low-cost aid that is designed and made to meet the needs of a particular child often works better than an expensive commercial one. For example:

Commercial wheelchairs are often too big for children, and hard to adapt to their positioning needs. Repairs are difficult and expensive; replacement parts are hard to get. LESS APPROPRIATE |

A simple wood or plywood chair can be easily made to fit the child's size and positioning needs. Repairs and replacements are easy because bicycle wheels and other standard parts are used. (See Page 620.) MORE APPROPRIATE |

4. Consider the economic limitations of the family and community. Growing children will frequently need larger sizes of aids such as leg braces, artificial limbs, and special seating. Use either aids that are cheap enough to replace often, or that can be easily made bigger. For example:

| When the child outgrows the brace,

or it breaks, the family cannot afford to repair or replace

it-so the child goes back to crawling, develops

contractures and may never walk again. Poor families sometimes spend as much as a year's earnings on an expensive, modern brace with knee and ankle hinges and special shoes.

LESS APPROPRIATE |

A cheap brace without hinges will not let the child bend his knee to sit. But the brace can be cheaply replaced, so the child is able to stay on his feet. Up to 20 low-cost braces can be made for the price of one expensive one.

MORE APPROPRIATE (See Page 543 and 586.)

5. Make use of the special opportunities in rural areas. Look for ways that a child can do her exercises as part of daily work and play with other people- not as a boring chore that keeps her separate and different. For example:

If a child needs a special aid to strengthen her weak arm,

| avoid making her do the exercises in a way that isolates

her.

LESS APPROPRIATE |

| Instead, find ways for her to do her exercises while

taking part in activities with others. Another child can help lower the grinder

MORE APPROPRIATE |

If the grinder is too heavy to lift, you can put another weight here.

In places where people grind grain with a handmill, this can also be used for exercises. So can grinding grain on a stone dish. A mill can be adjusted from 'easy' to 'hard'. (Also see Pages 6 and 377.)

6. Whenever a choice can be made, keep orthopedic aids as light and unnoticeable as possible. For example:

Tina is from a village where most children wear sandals. A rehabilitation center in the city fitted her with a heavy metal brace and boots like this. She hated them and refused to leave the house with them on. |

Six months later, Tina's father took her to a village rehabilitation center where they fitted her with a lightweight plastic brace. She could wear it under stockings, and still use her old sandals. She was happy to wear it anywhere.

|

Note: In areas where children do not wear shoes and socks, a brace with a wood clog, leaving most of the foot open to the air, may be preferred (and may be cleaner). |

7. Try to adapt aids and equipment to the local culture and way of life. An example of adaptation to the local situation is the'Jaipur limb' (see also Chapter 67):

In India, villagers squat a lot. They cook and eat at ground level. A person with a standard artificial leg cannot squat because the leg does not bend enough in the knee and ankle. Also, the standard leg is not made to be used when barefoot, or in water. |

| The 'Jaipur limb' was designed for the needs of villagers

in India. It has a knee with a joint that bends all the way.

The foot piece is made mostly of rubber and is very flexible,

allowing the person to squat. It is the color and shape

(including toes) of a normal foot. It is waterproof, so that

people can work in water-or rice fields without harming it.

The leg is low cost and quick to fit,

(For more information on the Jaipur limb, see Page 636.) |

8. Make aids and equipment as attractive and enjoyable as possible. To test the attractiveness of an aid, find out:

| Does the child take pleasure or pride in his aid? | |

| Do the parents like it? | |

| Do other children want to use it or play with it? |

9. A common error is to provide children with more bracing than they need. Often a child will come to the rehabilitation center already fitted with big heavy braces that he never needed or no longer needs. They may actually slow him down. Always check to see what a child can do with and without his aids. Try smaller, lighter aids, or none at all. Above all, ask the child what he prefers.

LESS APPROPRIATE |

MORE APPROPRIATE |

STILL MORE APPROPRIATE |

EVALUATING WHICH DEFORMITIES SHOULD BE CORRECTED AND WHICH SHOULD NOT

PART 3 of this book, in addition to aids and equipment, also discusses methods for correcting joint contractures, which are discussed in Chapter 59. Just as you need to decide if a brace is appropriate, you need to decide whether correcting a contracture will actually help a child. Although many contractures increase difficulty for a child, some may actually help and should be left uncorrected. For example:

In a child with polio, the weaker leg is often shorter. The foot hangs down and often develops a tiptoe contracture which, in effect, makes the leg longer |

If we correct the foot contracture, the leg will, in effect, become 'shorter'. This can cause tilting of the hips, a spinal curve, and more awkward walking. To correct the hip tilt and spinal curve, the child will need a lift on the shoe, and probably a brace too. This usually makes walking more difficult, and the disability more noticeable, than before the contracture was corrected. |

For this child it may be best NOT to correct the contracture.

Other examples of contractures that are sometimes more beneficial than harmful are finger contractures in persons with hand paralysis (see Page 183) and tightness of back muscles in persons with spinal cord injury or muscular dystrophy (see Page 375).

![]()

CAUTION: In children with spastic cerebral palsy, sometimes orthopedic surgeons perform operations to correct contractures or awkward positions, without completely evaluating the effects on the children. Often children find it harder to walk or function after the surgery. Always seek the opinion of therapists and other orthopedists before deciding to have the operation. |

Before deciding to correct any contractures or deformities, try to be sure that the correction will help the child to do things better.

WHAT IS MORE IMPORTANT-APPEARANCE OR FUNCTION?

When a choice needs to be made between an aid that is more useful and one that is more attractive (or perhaps no aid at all), it is important to consider the cultural factors and to respect the wishes of the child and her parents. Here is another story.

| A HELPING HAND FOR SRI When Sri was 13 years old, one day she was helping her father at a small sugar-cane mill that was pulled round and round by a mule. Her hand got caught in the gears of the mill and was crushed. It had to be cut off at the wrist. The stump healed quickly but Sri's spirit did not. It seemed as though it, too, had been crushed. She had been a happy girl. Now she just sat around. She did not help with housework, and refused to go outside. She kept her stump hidden in her clothing or behind her back. Sri's family worried about her. They took her to a specialist in the city who examined her and suggested an artificial limb. She gave Sri the choice between hooks, which would be useful, and an artificial hand, which looked more natural but would be less useful. The specialist encouraged her to choose the hooks, and explained how well she could learn to use them. But Sri picked the hand.

The hand was very expensive, but it looked almost real, and the family agreed. Her father had to sell his mule to pay for it, and was in debt for more than a year. As time went by, however, Sri never really used her new hand. She tried it on a few times, but it seemed cold and dead. One day when her mother took her to the market wearing the hand, Sri thought everyone was looking at her. Two little boys, who had been her friends, pointed at the hand and laughed. She never wore it again. One day a village health worker visited Sri's home. She saw that everyone was busy working and doing things except Sri, who sat quietly in the corner. After talking with her family, the health worker suggested that they make an effort to treat Sri just like the other children. ''Encourage her to help with work, and to take part in all your activities," she said. "Don't pretend that Sri's hand isn't missing. Just accept her as she is. Let her know that you love her and need her help as much as before." So instead of feeling sorry for Sri, or letting her just sit and feel sorry for herself, her family began to treat her as they had before the accident. They asked her to help with the housework, prepare the meals, and care for the baby. At first Sri was unwilling and found everything difficult. But soon she learned how to do many things by using her good hand and her stump. She began to gain new confidence in herself, and in time started going to the market alone. At first, people took notice of her missing hand, or whispered, 'Oh, poor thing!" But when they saw how well she did things, they soon stopped feeling sorry for her and began to treat her like any other person. |

|

|

When trying to decide about an aid, we need to seek the balance between usefulness and attractiveness that helps the child fit in best with his or her family and community.

Rehabilitation experts often place great importance on usefulness, or 'function'. But acceptance in the community is also very important. In some places it may be more important. So, before trying to convince a child like Sri to accept an aid that will make her deformity more noticeable, we must consider how this could affect her. In some communities, people will soon accept both the child and her aid. But in some societies, people have beliefs or deep fears about a person whose body is 'incomplete'. In other societies, amputation of a hand has traditionally been the punishment, and sign, of a thief. Or a girl who is seen as defective may not be likely to find a husband. So, it may be socially very important for her to have an aid that looks real or is less noticeable, even if it does not function. (If the family can afford them, sometimes the best solution is 2 artificial limbs - hooks for home use or work, and a 'hand' for 'dressing up' and going out.)

| APPEARANCE CAN BE IMPORTANT

For example, one of the most useful solutions to amputations of both hands is an operation which uses the two bones of the lower arm to create 'pinchers'. The operation is fairly simple for an orthopedic surgeon, and once completed no aids are needed for grasping and handling a wide variety of things. The biggest advantage is that the person can feel what he handles. But few people choose this alternative because, they say, it looks so strange. |

It is, of course, unfortunate that a child feels ashamed or thinks she has to hide her disability. We must work for greater understanding. But people do not change their attitudes quickly. Often the child and her parents have good reasons for their fears, and we must learn to accept them. However, we must also help the child, her family, and the community to become more accepting of the child's disability and to provide as many opportunities for the child as possible.

We need to help the child find courage. A child with a new disability will often be afraid to go out into the community, or back to school. And other persons or children may at first take notice and 'feel sorry' for her-or even tease her. But if she can be helped through this first difficult period, usually other people and children will soon get used to her 'difference' and accept both it and her. As more disabled persons find the courage to go out into the community, it will be easier for those who follow, because people will become more open and accepting.

In the story of Sri, the rehabilitation specialist tried to solve her problem by giving her an artificial limb. Her family spent a lot of money on it. But the new 'hand' did not solve her problem. She never really accepted or used it. Her problem, which was partly emotional, was finally solved by the whole family helping her to join them again in daily activities, and to gain new confidence in herself.

This is very important. Too often we try to find technical answers to problems that are mostly personal, social, or emotional. So we turn to special aids and equipment. Sometimes these are needed. But sometimes they are unnecessary, too costly, or make life more difficult for the child (even though they may be of some help physically). So ...

| Before deciding if a child needs special aids, braces, surgery, or equipment, and what kind, carefully consider the needs of the whole child within her family and community. |