Part 2

WORKING WITH THE COMMUNITY

Village Involvement in the

Rehabilitation, Social Integration,

and Rights of Disabled Children

![]()

CHAPTER 44

INTRODUCTION TO PART 2

Disabled Children in

the Community

In PART 1 of this book, we discussed ways of working with individual children according to their particular disabilities. However, a lot of what can make life better- or more difficult - for a child comes not from the child's disability itself, but from the way that people in the family and community look at and treat the child.

In this part of the book (PART 2) we look at ways to actively involve members of the community-disabled persons, their families, concerned adults, schoolchildren, and others-in meeting the needs of disabled children and in helping them find a meaningful place in the community.

| A DISABLED CHILD GROWING UP HAS THE SAME NEEDS AS OTHER CHILDREN, FOR... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In every society, disabled children have the same social needs as other children. They need to be loved and respected. They need to play and explore their world with other children and adults. They need opportunities to develop and use their bodies and minds to their fullest ability, whatever that may be. They need to feel welcome and appreciated by their family and in their community.

Unfortunately, in most villages and neighborhoods, disabled persons- including children-are not given the full chance they deserve. Too often people see in them only what is wrong or different without appreciating what is right.

DIFFERENT COMMUNITIES REQUIRE DIFFERENT APPROACHES

The way people treat disabled persons differs from family to family, community to community, and country to country.

| Local beliefs and customs sometimes cause people to look down on disabled persons. For example, in some places, people believe that children are born disabled or deformed because their parents did something bad, or displeased the gods. Or they may believe that a child was born defective to pay for her sins in an earlier life. In such cases, parents may feel that to correct a deformity or to limit the child's suffering would be to go against the will of the gods. | |

| Lack of correct information often leads to misunderstanding. For example, some people think that paralysis caused by polio or cerebral palsy is 'catching' (contagious), so they refuse to let their children go near a paralyzed child. | |

| In many societies, children who have fits or mental illness are said to be possessed by the devil or evil spirits. Such children may be feared, locked up, or beaten. | |

| Failure to recognize the value and possibilities of disabled persons may lead to their being neglected or abandoned. In many countries, parents give their disabled children to their grandparents to bring up. (in return, many of these children when they grow up take devoted care of their aging grandparents.) | |

| Fear of what is strange, different, or not understood explains a lot of people's negative feelings. For example, in communities where polio is common, a child who limps may be well accepted. However, in a community where few children have physical disabilities (or where most who do are kept hidden), the child with a limp may be teased cruelly or avoided by other children. | |

| How severe a disability is often influences

whether or not the family or community gives the child a fair

chance. In some parts of Africa, children with polio who manage to

walk, even with braces or crutches, have a good chance of becoming

well accepted into society. The opposite is true for children who

never manage to walk. Even though most could learn important

skills with their hands and perhaps become self-sufficient, the

majority of non-walkers die in childhood, largely from hunger or

neglect..

| |

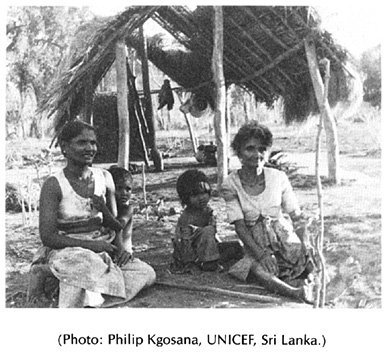

| Where poverty is extreme, a child's disability may seem of small importance. When this family in Sri Lanka was asked about their disabled child, the mother said her biggest worry was that the roof of their hut leaked. The village rehabilitation workers organized neighbors to help build a new roof. Only when the basic needs of food and shelter were met, could the mother give attention to her child's disability. |

Overprotection

Certainly not all disabled children are neglected or treated cruelly. In Latin America (where this book was written) a disabled child is often treated by the family with an enormous amount of love and concern. It is common for parents to spend their last peso trying to cure their child, or to buy her vitamins or sweets, even at the cost of hardship for the other children.

Providing too much protection is one of the biggest problems in Latin America and elsewhere. The family does almost everything for the child, and so holds her back from developing skills and learning to care for herself. Even a child with a fairly mild disability is often not allowed to play with other children or go to school because her parents fear she will be teased, or unable to do as well as the others.

Even in Latin America, where families usually provide loving care for their disabled children, they often keep them hidden away. Seldom do you see a disabled child playing in the streets, helping in the marketplace, or working in the fields. Partly because disabled persons are given so little chance to take part in the life of the community, everyone assumes that they cannot-and should not. Disabled children often grow up as outsiders in their own village or neighborhood. They are unable to work, unable to marry and have children, unable even to move about and relate freely to others in the community. This is not because their disabilities prevent them, but because society makes it so difficult.

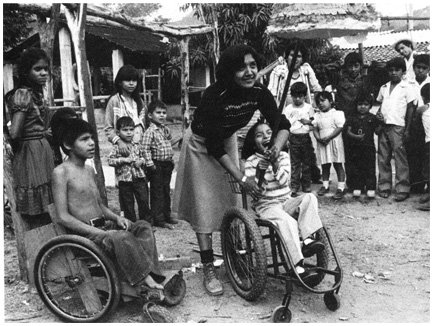

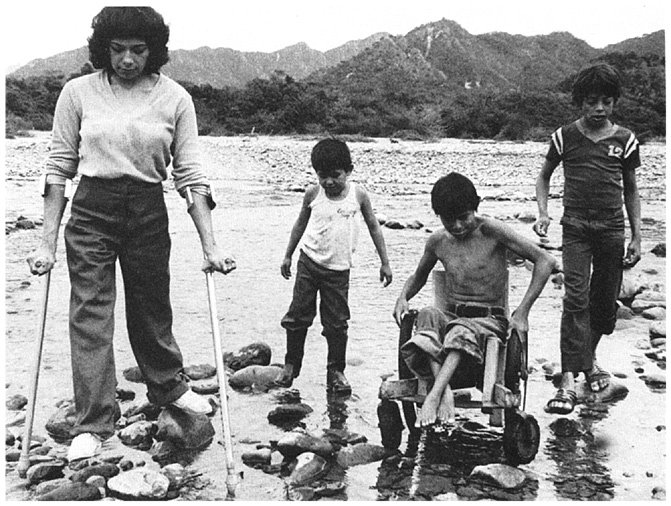

Yet things do not have to be like this. In the village of Ajoya, Mexico, people used to stare at, turn their backs on, or express their sorrow for the occasional disabled child whom they saw. But now things have changed. Ajoya has become the base of a community rehabilitation program (PROJIMO) run mainly by disabled young people.

In Ajoya, disabled children and their parents are now comfortable about being seen in public. Non-disabled and disabled children play together in a 'playground for all' built by the village children with their parents' help. The community has helped build special paths and ramps so wheelchair riders can get to the stores, to the village square, in and out of some homes, and to the outdoor movie on Saturday nights.

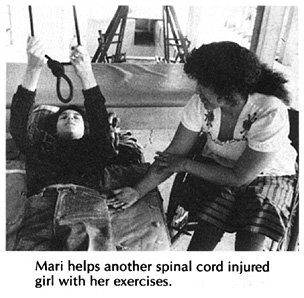

Mari, a young woman who is paraplegic (paralyzed from the waist down), first came to Ajoya from a neighboring village for rehabilitation. She soon became interested in the village program and decided to stay and become a worker. Today Mari keeps the records, helps interview and advise disabled children and their families, and is learning how to make plastic leg braces. She has become one of the most important members of the PROJIMO team.

But Mari does not want to go back to her own village. "It's depressing there!" she says. "I never go out of the house. I don't want to. The people don't treat me like myself anymore. They don't even treat me like a person. They treat me like a cripple, a nothing. One time I tried to kill myself. But here in Ajoya it's a different world! People treat me just like anybody else. I love it here! And I feel useful."

Her fellow team members in the village rehabilitation center are trying to convince Mari to go back sometime to her own village as a rehabilitation worker. They offer to help her change people's attitudes there, too. Mari is still uncertain. But the PROJIMO team has begun to visit Mari's village. Already the families of disabled children there have begun to organize. The village children have helped build a "playground for all', and adults have built a small 'rehabilitation post' next to it. So, things have begun to change in Mari's village too. The 'different world' has begun to grow and spread.

In PART 2 of this book we look at ways to help the community respond more favorably to disabled children and their needs. Usually, of course, a village or neighborhood does not decide, on its own account, to offer greater assistance, acceptance, and opportunity to disabled persons and their families. Rather, disabled persons and their families must begin to work together, to look for resources, and to re-educate both themselves and their community. Finally-when they gain enough popular understanding and support-they can insist on their rights.

The different chapters in PART 2 discuss various approaches and possibilities for bringing about greater understanding of the needs and possibilities of disabled children in their communities. We start by looking at what disabled persons and their families can do for themselves and each other. We look at possibilities for starting a family-based rehabilitation program, and the importance of starting community-directed rehabilitation centers run by disabled villagers themselves. We explore ways to include village families and school children. Finally, we look at specific needs of the disabled child growing up within the community- needs for group play, schooling, friendships, respect, self-reliance, social activities, ways to earn a living or to serve others; also needs for love, marriage, and family.

EXAMPLES, NOT ADVICE

In this part of the book, which deals with community issues, we will try mostly to give examples rather than advice. When it comes to questions of attitudes, customs, and social processes, advice from any outsider to a particular community or culture can be dangerous. So as you read the experiences and examples given in these pages, do not take them as instructions for action. Use, adapt, or reject them according to the reality of the people, culture, needs, and possibilities within your own village or community.

| Each community is unique and has its own obstacles and possibilities. |