| 113

|

CHAPTER 18

A Low-Cost Stump-Cast Clamp

for Making Artficial Legs

Experimenting with Village-Made Limbs

In Mexico, there are thousands of people who need an artificial leg, but

don't have the money to buy one. A modern above-the-knee prosthesis often

costs a farm laborer or factory worker twice his or her yearly wages.

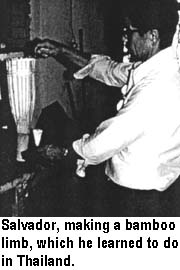

The PROJIMO team has experimented with different kinds of low-cost legs.

They sent a villager to Thailand to be an apprentice for making bamboo

limbs, molded leather sockets, and wooden knee-joints. (All of these are

pictured in the book, Disabled Village Children.) Some of the

"appropriate technology" legs worked very well. But - alas! - most people

did not like them: they said they looked too primitive. They had seen fancy

limbs made of fiberglass, and they wanted something "modern."

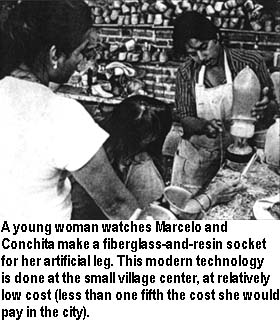

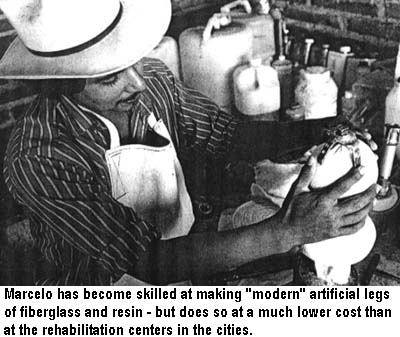

In response to users' wishes, PROJIMO arranged for a team member,

Florentino, to apprentice for two weeks in a limb-making shop in a distant

city. There he learned the basics of making fiberglass-and-resin limbs. When

he returned, Florentino improved his skills by trial and error. He shared

what he knew with Marcelo Acevedo, who in time became a master limb-maker.

Marcelo, in turn, taught Guadalupe (himself an amputee), Conchita (see

Chapter 42), and others.

PROJIMO has been able to fit persons with modern fiber-glass legs at a

much lower cost than they could find elsewhere. While quality varies, these

limbs tend to be better than those made at much higher cost by professionals

in the cities. Two government rehabilitation programs have contracted with

PROJIMO to fit their clients with these artificial legs.

The PROJIMO leg-makers (mostly disabled) have had little formal training,

They learn by doing. Although their technical skills may not equal

those of highly trained technicians, it is their relationship with the

persons receiving limbs that makes all the difference. Often the

person stays several days, and becomes involved in fitting and building the

limb. After it is done, she spends the next days at PROJIMO learning how to

walk with it. Efforts are made to fix any problems, even when this means

remaking the leg.

A good limb is the result of a close working relationship between

builder and user. |

| 114

|

LOW-COST MATERIALS AND SECOND-HAND PARTS

Marcelo and the other limb makers at PROJIMO have devised several

techniques for making modern fiberglass-socket limbs at lower cost.

Whenever possible, they try to get high-quality knee-joints from discarded

limbs (often those of elderly persons with diabetes who have died).

Support persons and groups in the USA and elsewhere are on the lookout for

second-hand joints, foot pieces, and other parts. Where such recycling is

possible, top-quality limbs can be provided at affordable prices.

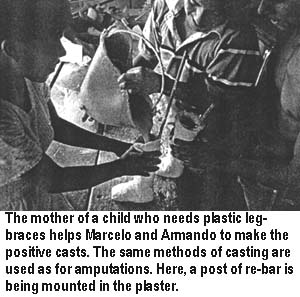

To make a limb that fits well, the first step is to cast the person's

stump. First, the technician makes a "negative" (hollow) cast of the stump

by wrapping a plaster bandage over the stump. Next, the technician makes a

"positive" (solid) mold, by filling the hollow cast with plaster.

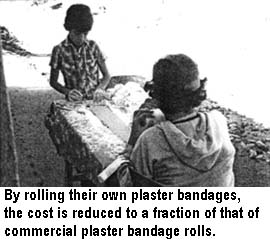

The team has found ways to keep down the costs. First, they have

experimented with roll-your-own plaster bandages, rather

than buying expensive commercial plaster bandages. With these home-made

plaster rolls, casting the stump is somewhat more difficult, but the cost

is only about one tenth that of the commercial equivalent.

The time it takes for the plaster to set (that is, to

get hard after wetting it with water) can be controlled in 2 ways. To

speed up the setting time, add a small amount of salt (ordinary table

salt) to the unset plaster powder. Or add a little powder from old plaster

that has already set. (The dust that collects from filing plaster molds

works well.) CAUTION: Hot weather or warm water also speeds up the

setting time, so local experimenting is necessary.

For making positive casts, the village leg-makers use low-cost plaster

sold for building houses; instead of costly orthopedic plaster-of-Paris.

Most limb makers, when they make a positive cast, put into it a 1/2

inch metal water-pipe. The pipe is used to grip the heavy stump-cast in a

vise while it is being "modified" (shaped into a form for molding the

socket).

Instead of the metal pipe, PROJIMO uses re-bar

(reinforcing rod, used in the cement walls of buildings). It is cheaper. |

| 115

|

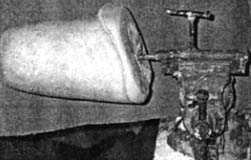

A CLAMP TO HOLD THE STUMP-CAST

Problem: To position and reposition the heavy stump

cast while modifying it to form the mold for the socket of the artificial

limb, a clamp is needed to hold it securely. Most high-class prosthetic

(artificial limb) shops have a strong, factory-made clamp. But this is

expensive (the equivalent of about US $130). For this reason, PROJIMO's

leg-makers simply used a bench-vise to grip the metal rod which they had

molded into the cast.

However, with the force used in filing and shaping the cast, the bar

often slipped in the vise. Also, the cast needed to be rotated repeatedly

during modification. To do this, the vise had to be loosened, and the

heavy cast had to be held in the right position while tightening the vise.

For a big heavy cast this often took two persons.

Solution: One time a North American limb-maker, John

Fago, was visiting PROJIMO to help the team up-grade their skills. John is

an amputee who first came to the project as a photographer. (Several

photos in this book are by John.) After visiting PROJIMO, John decided to

get training as a prosthetist, in order to help in the development of

low-cost, high-quality limbs, (He now runs a small, non-profit program

called New Legs for Nomads.) Marcelo explained to John the

difficulty he had in trying to hold the stump-cast in a bench vise.

Together, Marcelo and John set about designing a simple stump-cast

clamp which would hold the cast securely, yet also allow it to be easily

and quickly repositioned.

Usefulness elsewhere. The clamp was put together out

of scrap metal in about 1 hour. It works remarkably well, allowing the

cast to be effortlessly rotated and re-clamped.

The innovation proved so popular that Javier, who worked in the brace

shop, took one look at it and immediately made one to hold casts for

making orthopedic appliances.

A few months later, John Fago took his photos of the clamp to Cambodia

(where tens of thousands of people have lost their legs from stepping on

land mines - see page 173). Limb-makers in

small shops there faced similar problems and, on seeing the photos, at

once made their own cast clamps - adapting the PROJIMO design to local

materials. So PROJIMO, which had originally taken some of its appropriate

technology ideas from grassroots limb shops in the Far East, was able to

return a useful innovation. |

| 116

|

How Good Ideas Spread

From Mexico ...

John Fago showed photos like these of PROJIMO's stump-cast clamp to

village limb makers in Cambodia.

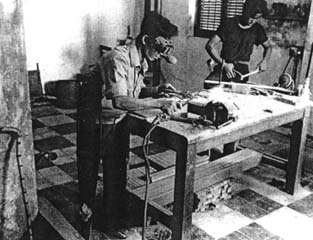

... to Cambodia

When the Cambodian limb-makers (who also had disabilities) saw John's

photos, they realized how much easier it could make their work, and

promptly made their own, as shown here.

|

| 117

|

The Key to Making Legs is Making Friends

|

|

|

|

| Conchita and Marcelo have worked hard

to learn how to make modern fiber-glass-and-resin limbs, because this

is what people say they want. |

Before she finishes a limb, Conchita

makes sure it fits well. Here, a man tests his new leg while Conchita

assists him in learning to walk.* |

Walking is easier with the arms

straighter. |

_________________________________________

*CAUTION: Reviewers of this book have rightly pointed out that

this man's walker is too high (as are the crutches of the smiling boy on

page 273). His elbows are bent far too

much. For easier walking on walkers, crutches, or parallel bars, usually

the arms should be nearly straight (see page 11).

Conchita, of course, could argue that the high walker encourages its user

to bear more weight on his new leg. What do you think? |

| 118

|

|

|

|