| 267

|

CHAPTER 43

Disabled Gangsters Help a Child

with Muscular Dystrophy

Creating an Environment That Brings Unexpected Improvement in

Children with Muscular Dystrophy

Muscular dystrophy is a condition in which muscles gradually become

weaker and weaker. Most specialists agree that nothing can be done to help

the child regain lost strength. This may be true in the long run. But we

have seen some children seem to get stronger, at least for a limited time.

ABEL, for example, is a boy with Duchenne's muscular

dystrophy. His arms had grown so weak that he could not push his

wheelchair more than a few inches on a flat surface. His parents wheeled

him everywhere. While at PROJIMO, Abel gradually regained enough strength

to wheel himself around the whole yard. In doing so, he gained a new sense

of self-determination.

Over a period of 3 years, as his dystrophy slowly progressed, Abel

again lost his capacity to propel his wheelchair. But for years he had

achieved greater independence of movement - an ability which he, his

parents, and his doctors had assumed was permanently lost.

Although a child with muscular dystrophy has slowly diminishing

muscular potential, it appears that, at any stage of his

condition, his strength and physical ability can be increased to more

closely approach his potential at that stage.

Abel's increase in strength and ability at PROJIMO was probably the

result of several factors: increased activity,

increased motivation, and increased

expectation by others. At home, his parents had done

everything for him. They had kept him away from activities and adventures

they feared might tire him. But at PROJIMO, Abel was encouraged to do as

much as he could for himself. Also, he had excellent role models,

including persons who were quadriplegic (paralyzed from the shoulders

down), yet who were largely independent in self-care.

Creating an environment that brings unexpected improvement - in

gangsters.

There is an old saying: "Poor Mexico, so far from God and so close to

the United States!" Mexico's huge foreign debt, falling wages, growing

unemployment, and pressure from the US to weaken Mexican laws protecting

small farmers have all increased the hardships for most Mexicans.

Since the start of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in

1994, over 2 million peasants have been forced off their land to join the

jobless multitudes in Mexico's swelling city slums. As the gap widens

between rich and poor, millions of street children and youth struggle to

survive through odd jobs, stealing, prostitution, and drug trafficking.

Crime rates, violence, and police brutality have drastically increased.

This growing "sub-culture of violence" has brought new difficulties and

challenges to PROJIMO. The small village program has had to attend to over

400 spinal-cord injured youths, mostly disabled by bullet wounds, from all

over Mexico. |

| 268

|

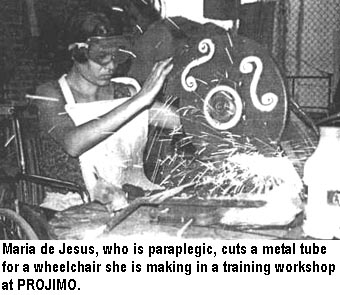

| Dilemma for PROJIMO. When

these newly disabled street-youths and gangsters arrive at PROJIMO, most

are angry and depressed. Many have been heavy users of alcohol and

drugs. Becoming physically disabled does not automatically end their

habits of violence, crime, and drugs. PROJIMO has, within the program,

had to deal with acts of violence, armed assault, drug trafficking and

use, drunkenness, attempted rape, and attempted murder. The team has

sought new ways to deal with the complex needs of young men and women

(mostly men) who are both physically and psycho-socially disabled. It

has not been easy. PROJIMO has set rules of behavior prohibiting

alcohol, drugs, and violence within its grounds. Those who break the

rules are threatened with expulsion. But it is not easy to throw

out someone who has dangerous pressure sores or other life-threatening

problems. Many have no home to return to. To send them back to

the city streets can be a death sentence. One young quadriplegic man who

was expelled from PROJIMO died from pressure sores 3 months later.

One of the worst acts of violence at PROJIMO was when two young men,

who had been shot through the spine in gang fights, got high on drugs

and booze. They attacked a retired, diabetic school teacher who was

being fitted for an artificial leg. They tried to stab him as he lay on

his bed. The terrified teacher shielded himself with an electric fan

until help arrived.

To cope with this problem, PROJIMO sought help from an

Alcoholics-and-Drugs-Anonymous program run by recovering addicts in the

city of Guadalajara. On his return to PROJIMO, one of these two young

offenders became a peer counselor for other young people hooked on

drugs. He helped a lot of youths get control of their lives before he

himself had a relapse, again became violent, and voluntarily left

PROJIMO.

What has been wonderful, however, has been the

apparent transformation within several of these young gangsters and

drug-dealers during their stay at PROJIMO. Some of the young

men, who seemed the most mean-spirited and aggressive when they came,

have become among the most helpful and caring members of the PROJIMO

team. In this book's Introduction (on

page 3) we mentioned Quique, who was so

supportive with José, a mentally handicapped little boy whom no one else

was able to reach. Another example is Martín Pérez, who became one of

PROJIMO's most gifted wheelchair and gurney designers (see Chapters

37 and 39).

Martín showed heart-felt concern for those difficult children whose

behavior sometimes led attendants to dislike or neglect them. When

Martín, like Quique, was finally thrown out of PROJIMO for repeated drug

use; one young girl, Tere, wept. "Martín was always the first to help me

if my wheelchair broke, or when I needed somebody to talk to who really

listened and cared," she said.

Seeing this kind of change from angry hoodlum to tender care-provider

or creative craftsperson has given many of us more insight into human

nature. It seems true that inside every person, however brutish

their exterior, there is a hidden seed of goodness, a seed of

compassion waiting for a chance to grow and flower. The longer that core

remains dormant and unrealized, the more urgent is its need for

fulfillment. Sometimes all it takes to start that seed sprouting is a

friendly word, an expectation of good will, a recognition that the

person has worth ... or a request for help when it is sorely needed.

With the right word or touch, the toughest thug may suddenly shed his

hard shell and offer heart-warming assistance and concern. And in the

process, he discovers joy in doing something loving and lovable. |

| 269

|

Angel - a Six-Year-Old Boy with Muscular Dystrophy

ANGEL was brought to PROJIMO by his mother from the

village of San Augustine, 40 kilometers away. Mari and Conchita did

their best to get the boy to relax and to win his trust. They talked to

him in a friendly way and offered him toys to play with. But Angel clung

fearfully to his mother and would burst into tears when asked a question

or when gently touched.

Angel's mother said the boy had difficulty walking and that his

condition was getting worse. She said she had taken him to doctors in

the city, who had prescribed everything from painkillers (although he

had no pain) to vitamins, calcium, hormones, and injectable antibiotics.

But his walking kept getting worse.

Mari and Conchita asked Angel's mother to walk across the room. She

did so, and Angel followed her. He had a waddling gait, throwing his

weight from side to side, a sign of weakness at the sides of the hips.

His calf muscles were unusually large for his thin body, and he walked

slightly on tip-toe. He had trouble lifting his arms over his head. In

order to stand up from the floor, he climbed up his body using his arms.

Although there was apparently no famify history (no relatives with a

similar condition), Mari recognized Angel's gradually increasing muscle

weakness as typical of Duchenne's muscular dystrophy.

Conchita was also concerned about Angel's emotional and social

development. He was very insecure and fearful of strangers. His mother

explained that he was not used to strangers. He did not go to school,

she said, because other children teased him and said he "walked like a

goose." (This made me recall how I was teased as a child, see

page 83.)

Possible Actions: The PROJIMO team gently

explained to Angel's mother that muscular dystrophy is a condition in

which the boy's muscles gradually get weaker. To date, no medical cure

has been found. But they helped her to realize that certain things could

be done to help her son live a fuller, happier life.

They also discussed with her different forms of "therapy." They

stressed that therapy - if used at all - should be approached in ways

that help, rather than block, the child's social, emotional, and mental

development. They told her about the exciting and rewarding life of the

Peraza family, in which 4 children with muscular dystrophy became

leaders and teachers in a program for disabled children (see

Chapter 48).

Mari also told Angel's mother something about experimental

alternatives, including intensive "massage therapy." The PROJIMO team

had learned about this from a visiting massage therapist, Marybetts

Sinclair. Although they could not promise improvement and the therapy

was described as controversial, Angel's mother was eager to try it.

Because Marybetts would be visiting again in a few weeks, they invited

Angel and his mother to return at that time.

Innovative management of muscular dystrophy: massage

therapy combined with physical therapy. The controversial new

treatment for muscular dystrophy mentioned above has been promoted by a

self-made therapist named Meir Schneider, who now practices in San

Francisco, California. Schneider claims that an intensive program of

massage therapy can halt the progression of muscular dystrophy and help

to return lost muscle strength. Although many medical professionals are

skeptical of Schneider's claims, Marybetts Sinclair, the massage

therapist who occasionally volunteers at PROJIMO, has shown the team

documents and films supporting his approach. Everyone agreed that

perhaps it was worth a try. |

| 270

|

| Working and playing with Angel.

Angel and his mother returned to PROJIMO as agreed. A physical therapist

from Australia who was then volunteering at PROJIMO was skeptical about

Schneider's methodology. Additionally, he insisted there was "no way"

that such an intensive massage program could be applied to a child as

fretful and uncooperative as Angel. Everyone agreed that any

attempt at therapy would need to be approached slowly and gently, as

much as possible in the form of play, while trying to gradually win

Angel's confidence and trust. A flexible schedule was

developed combining therapeutic massage and physical therapy.

They began with brief sessions and planned to gradually build up to

several hours a day. The challenge was to make the experimental approach

interesting, varied, and fun enough for Angel to accept and enjoy it.

Sessions of massage followed by exercise games

were followed with play on the swings, rocking horses, and other

equipment on the outdoor Playground for All Children. To

encourage interaction with a variety of people (and to divide up the

work), nearly a dozen disabled and non-disabled persons were recruited

to help.

The therapeutic massage, in keeping with Schneider's recommendations,

consisted of gentle circular motions with the finger-tips over the whole

body, concentrating on the most important and affected muscles. At first

- as predicted - the boy was fearful of being touched by anyone but his

mother. But his helpers were gentle and his mother also took part. The

massage was so soothing that the boy gradually relaxed and began to

enjoy it. By the third day he was eager for more.

Exercise activities, mostly through play, were

combined with and followed the massage. These were designed to encourage

a full range of motion, as much as possible through

active muscle use, yet without causing fatigue. Simple

games were devised, inviting the boy to touch or hit another person's

hand or to kick a ball with his outstretched foot. Each time, he was

encouraged to stretch a little farther or reach a little higher. He

would proudly count how many times he could repeat each action. (Thus,

his counting skills increased along with his physical skills.)

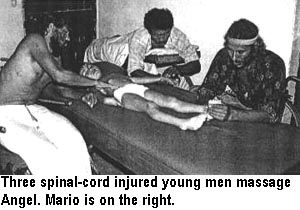

Gangsters as therapists.

Although at first many persons at PROJIMO assisted with Angel's

therapy, after a few days fewer people arrived to take part. Among those

who showed greatest persistence and concern were some of the "gangsters"

and street youth who had been disabled in gun fights. Day after day,

three paraplegic young men would circle the couch on which Angel lay,

gently providing massage and playful exercise. Angel gradually grew

comfortable with them, laughing with delight at the games.

These young men clearly took pride and joy in helping little Angel,

and in seeing him respond so enthusiastically to their efforts. It was

good therapy for everyone. |

| 271

|

| The gentle side of a tough guy.

One of the spinal-cord injured young men who showed the most care and

innovativeness in working and playing with Angel was Mario. Perhaps

Mario missed his own childhood (which he had never really had). Or

perhaps he missed his only child, who had died. In any case, Mario

sympathized with Angel's fragile vulnerability. MARIO

had grown up as a street child and, since boyhood, had trafficked in and

used drugs. In his 20s he decided to turn over a new leaf. He married

and settled down on a ranch. But old gang rivalry caught up with him in

the form of a drive-by shooting. The same bullet which left Mario

paraplegic passed through his baby daughter in his arms. Weeks later, in

revenge, his brothers captured the culprits. From his wheelchair, Mario

watched as his bothers tortured them to death.

In retrospect, Mario does not try to justify this action, but sadly

explains: "They killed my baby."

For all that, Mario has a gentle side, a depth of caring that is

sometimes born of pain. At PROJIMO, where he stayed for a long time

while his deep pressure sores gradually healed, Mario learned carpentry

skills and began to help in the wood-working shop.

In time, Mario became a skilled craftsperson, making special seating

and personalized equipment for children with special needs. He was quite

creative. But the main reason that his innovations often turned out well

was because he worked so closely with the child and his parents.

Children liked him because he listened to them and related to them on

their terms. He no longer had interest in maintaining the macho (manly)

distance and toughness so typical of grown-up males. He'd had enough of

all that.

With Angel, Mario was both imaginative and creative - and playful in

a non-threatening way. He was constantly coming up with new ideas to

turn Angel's therapy into games. Angel loved it, and became very

attached to Mario.

Here are some of the ideas that Mario and his co-workers came up with

to motivate Angel and to turn his therapy into play.

The leaf-on-a-stick balancing act, to improve gait.

Although part of Angel's side-to-side pendulum-like gait was due to

reduced muscle strength at the sides of his hips, the weakness and

outward (varus) collapse of his ankles also was a factor. After Raymundo

custom-fitted him with light-weight plastic ankle-braces (AFOs, see

page 86), his gait improved. When

prompted, Angel could walk without lurching as much from side to side.

But, partly due to habit, he would quickly fall back into the old wobbly

pattern.

To help him learn to walk without lurching so much from side to side,

Mario invented a simple game.

Angel would hold a thin pole upright with a mango leaf bent over its

tip. The boy would then try to walk across the room without the leaf

falling. To do this, he had to walk smoothly, keep his body steady, and

not lurch sideways. When he succeeded (as he did more and more often)

everyone clapped. After a few days, Angel's gait showed noticeable

improvement, even when he was not playing the game. He also held his

head higher. |

| 272

|

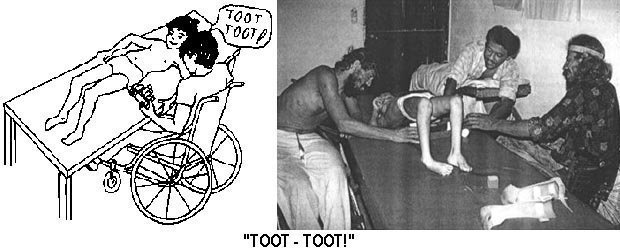

The truck-under-the-bridge game - to exercise the belly and

back.

To help him use his stomach and back muscles, the PROJIMO team asked

Angel to lie first on his belly, then on his back, and arch his body

upwards. To turn this into a game, Mario asked a group of school

children in the toy shop to make a toy truck loaded with brightly

colored blocks of different heights.

Angel at once fell in love with the truck ... and the exercises that

came with it. As Angel lay on his back, Mario or another one of the

therapy helpers would drive the truck in circles around Angel. They

would toot loudly as the truck approached his mid-section. At the toot,

Angel would arch his body upwards to let the truck pass under the

"bridge" formed by his body. When this game began, Mario started with

shorter blocks so that Angel would not have to lift very high. But as

his ability to lift his body increased, Angel helped Mario to load the

truck with taller blocks. This gave the boy more of a challenge. Angel

enjoyed the game and did his best to "lift the bridge" for the tallest

truck-load of blocks.

|

| 273

|

RESULTS:

On evaluating the therapeutic activities that were used with

Angel, it is important to consider their effect on the whole child -

physically, emotionally, and socially - not just the specific objectives

that the activities were designed to meet.

Physically, the combination of Angel's massage

therapy, exercise, and increased activity appeared to have a

limited but positive effect. During two weeks at PROJIMO, the

boy's gait improved visibly. There were also gains in his capacity to do

things that involve lifting and moving different parts of his body.

After Angel returned to his home, his mother continued with the

massage and exercise games. When Angel came back to PROJIMO 3 months

later, many people commented that his walking had improved even more.

We still do not know the long-term outcome. Despite apparent

short-term improvements, we can not presume that progressive muscle loss

has been reversed or halted. Rather, we suspect that the plentiful

stimulation and modest (non-fatiguing) use of under-used muscles helped

put his body in more optimal condition, within its given stage of

deterioration. It stands to reason that, as the dystrophy advances,

reduced activity will add to the degenerative process. By contrast,

keeping the body in its best possible physical shape may slow muscle

loss and bring at least temporary improvement in body function.

Emotionally and socially, Angel improved enormously.

During his stay at PROJIMO, he changed from a whiny, clinging little boy

who feared everyone but his mother, into a playful child who enjoyed the

closeness and attention of other people.

Angel's physical condition will probably continue to deteriorate,

possibly more slowly than it might have otherwise. But his mind and

spirit will continue to develop - perhaps more openly, fully, and

happily than they might have without the warm, friendly touch of folks

like Mario at PROJIMO.

In the last analysis, perhaps the best indicator of an activity's

success is the smile factor. Certainly, Angel smiles

more than he used to!

___________________________

WARNING: Though the boy in this photo is smiling

now, his poorly adjusted crutches may cause more disability later. With

his elbows so bent, he cannot support his weight on his hands, and so he

supports himself under his arm-pits. This can damage nerves and

gradually paralyze his hands. See the suggestions on pages

12 and 117

... THE SMILE MUST NOT BE THE ONLY MEASURE OF SUCCESS. |

| 274

|

|

|

|