| A1 | ||||

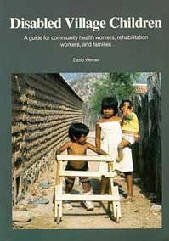

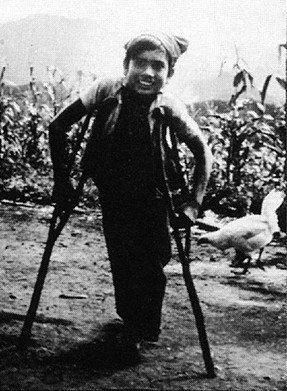

ABOUT THIS BOOKA TRUE STORY: CRUTCHES FOR PEPEA teacher of village health workers was helping as a volunteer in the mountains of western Mexico. One day he arrived on muleback at a small village. A father came up to him and asked if he could cure his son. The health worker went with the father to his hut. The boy, whose name was Pepe, was sitting on the floor. His

legs had been paralyzed by polio, from when he was a baby. The health worker, who also had a physical disability, examined Pepe. "Have you ever tried to walk with crutches?" he asked. Pepe shook his head. "We live so far away from the city," his father explained. "Let's try to make some crutches," said the health worker. The next morning the health worker got up at dawn. He borrowed a long curved knife and went into the forest. He looked and looked until he found 2 forked branches the right size.

|

![]()

| A2 | ||||||

|

||||||

![]()

| A3 | |||

HOW THIS BOOK WAS WRITTENThe story of Pepe's crutches is an example of the lessons we have learned that helped to create this book. We are a group of village health and rehabilitation workers who have worked with people in farming communities of western Mexico to form a 'villager-run' rehabilitation program. Most of us on the rehabilitation 'team' are disabled ourselves. From our experience of trying to help disabled children and their families to meet their needs, we have developed many of the methods, aids, and ideas in this book. We have also gathered ideas from books, persons, and other programs, and have adapted them to fit the limitations and possibilities of our village area. We hope this book will be useful to village people in many parts of the world. So we have asked for cooperation and included suggestions from community program leaders in more than 20 countries.

|

![]()

| A4 |

HOW THIS BOOK DIFFERS FROM OTHER

'REHABILITATION MANUALS'

This book was written from the 'bottom up', working closely with disabled persons and their families. We believe that those with the most personal experience of disability can and should become leaders in resolving the needs of the disabled. In fact, the main author of this book (David Werner) and many of its contributors happen to be disabled. We are neither proud nor ashamed of this. But we do realize that in some ways our disabilities contribute to our abilities and strengths.

In many rehabilitation manuals, disabled persons are treated as objects to be worked upon, to be 'normalized' or made as normal as possible. As disabled persons, we object to attempts by the experts to fit us into the mold of normal. Too often 'normal' behavior in our society is selfish, greedy, narrow-minded, prejudiced-and cruel to those who are weaker or different from others. We live in a world where too often it is 'normal' and acceptable for the rich to live at the expense of the poor, and for health professionals to earn many times the wages of those who produce their food but cannot afford their services. We live on a wealthy planet where most children do not get enough to eat, where half the people have never seen a trained health worker, and where poverty is a major cause of disability and early death. And yet the world's leaders spend 50 billion dollars every 3 weeks on the instruments of war-an amount that could provide primary health care to everyone on earth for an entire year!

Instead of being 'normalized' into such an unkind, unfair, and unreasonable social structure, we disabled persons would do better to join together with all who are treated unfairly, in order to work for a new social order that is kinder, more just, and more sane.

This large book, then, is a small tool in the struggle not only for the liberation of the disabled, but for their solidarity in the larger effort to create a world where more value is placed on being human than on being 'normal'-a world where war and poverty and despair no longer disable the children of today, who are the leaders of tomorrow.

Top-down rehabilitation manuals too often only give orders telling the 'local trainer', family member, and disabled person exactly what they 'must do'. We feel that this is a limiting rather than liberating approach. It encourages people to obediently fit the child into a standard 'rehabilitation plan', instead of creating a plan that fits and frees the child. Again and again we see exercises, lessons, braces, and aids incorrectly, painfully, and often harmfully applied. This is done both by community rehabilitation workers and by professionals, because they have been taught to follow standard instructions or pre-packaged solutions rather than to respond in a flexible and creative way to the needs of the whole child.

In this book we try not to tell anyone what they must do. Instead we provide information, explanations, suggestions, examples, and ideas. We encourage an imaginative, adventurous, thoughtful, and even playful approach. After all, each disabled child is different and will be helped most by approaches and activities that are lovingly adapted to her specific abilities and needs.

![]()

| A5 |

As much as we can, we try to explain basic principles and give reasons for doing things. After village rehabilitation workers and parents understand the basic principles behind different rehabilitation activities, exercises, or aids, they can begin to make adaptations. They can make better use of local resources and of the unique opportunities that exist in their own rural area. In this way many rehabilitation aids, exercises, and activities can be made or done in ways that integrate rather than separate the child from the day-to-day life in the community.

This is not the first handbook of 'simplified rehabilitation'. We have drawn on ideas from many other sources. We would like to give special credit to the World Health Organization's manual, Training the Disabled In the Community, and to UNICEF and Rehabilitation International's Childhood Disability: Prevention and Rehabilitation at the Community Level, a shortened and improved version of the WHO manual. The WHO manual has recently been rewritten in a friendlier style that invites users to take more of a problem-solving approach instead of simply following instructions.

This handbook is not intended to replace these earlier manuals. It provides additional information. It is for those families, village health workers, and community rehabilitation workers who want to do a more complete job of meeting the needs of physically disabled children.

HOW WE DECIDED WHICH DISABILITIES TO INCLUDE

Because this book is written for village use in many countries, it was not easy to decide what to include. People in different parts of the world give importance to different disabilities. This is partly because some disabilities are much more common in one area than another. For example,

| polio in some countries is the most common disability. In others, it is rare because of effective vaccination programs. | |

| deafness and mental retardation are much more common in certain mountain regions because of lack of iodine in the diet (or in salt). | |

| blindness due to lack of vitamin A is common in some poor crowded communities, and depends a lot on local food habits. | |

| rickets is still common in regions where children are wrapped up or kept in dark places so much that they do not get enough sunlight. | |

| burn deformities are frequent where people cook and sleep on the ground near open fires. | |

| amputations are a big problem in war zones, refugee camps, and 'shanty towns' along railway tracks. | |

| disability from tuberculosis, leprosy, measles, malnutrition, and poor sanitation are especially common where lack of social justice lets some people live in great wealth while most live in extreme poverty. |

Local beliefs also affect how people see different disabilities. In an area where people believe that fits are the work of the devil, a child with fits may be feared, teased, or kept hidden. But in places where everyone accepts fits as 'just something that happens to certain persons' a child who sometimes has fits may participate fully in the day-to-day life of the community, without being seen as 'handicapped'. Both of these children need medicine. But probably only the mistreated one needs 'rehabilitation'.

![]()

| A6 | |||||||||||||

| It is important to consider how local people

see a child who is in some way 'different'. How do they accept

or treat the child who learns slowly, limps a little, or

occasionally has fits? Many reports say that in both rich and poor countries, 1 in 10 children are disabled. However, this number can be misleading. Although 1 child in 10 may show some defect if examined carefully, most of these defects are so minor that they do not affect the child's ability to lead a full, active life. In rural areas, children who are physically strong but are slow learners often fit into the life and work of the village without special notice. In India, a study found that only 1 in 7 of those recorded as mentally retarded by screening tests were seen as retarded by the community. Studies in several countries show that, on the average, only 2 or 3 children in 100 are considered disabled by the community. These are the children most likely to benefit from 'rehabilitation'.

---------------================----------------- When we started to write this book, we planned to include only physical disabilities. This is because concerned villagers and health workers in rural Mexico considered physical handicaps to be the area of greatest need. This is understandable. In poor farming communities, where many day-to-day activities depend on physical strength, and where schooling for most children is brief, the physically disabled child can have an especially difficult time fitting in. By contrast, in a middle-class city neighborhood, where children are judged mainly by their ability in school, it is the mentally slow child who often has the hardest time.

|

![]()

| A7 | ||

| The team of disabled village workers in Mexico

was at first concerned mostly with physical disabilities. But

they soon realized that they also had to learn about other

disabilities. Even children whose main problem was physical,

like polio, were often held back by other (secondary) emotional,

social or behavioral disabilities. And many children with brain

damage not only had difficulties with movement, but also were

slow learners, had fits, or could not see or hear. As the PROJIMO team's need for information on different disabilities has grown, so has this book. The main focus is still on physical disabilities, which are covered in more detail. However, the book now includes a fairly complete (but less detailed) coverage of mental retardation and developmental delay (slow learning). Fits (epilepsy) are also covered. Blindness and deafness are included, but only in a very brief, beginner's way. This is partly because we at PROJIMO still do not have much experience in these areas. And partly it is because seeing and hearing disabilities require so much special information that they need to be covered in separate books. Some fairly good instructional material is available on these disabilities, especially on blindness. We list some of the best materials that we know on Page 639 and 640.

To decide which disabilities to put in this book and how much importance to give to each, we used information from several sources, including the records of Project PROJIMO in Mexico. We found that the numbers of children with different disabilities who came to PROJIMO were fairly similar to those in studies done by WHO, UNICEF, and others in different areas of the world. On the next page is a chart showing how many children with each disability might be seen in a typical village area. (Of course, there is no such thing as a 'typical' village. The patterns of disability in some areas will be quite different from those shown on the chart.) The chart is based mainly on our records from PROJIMO over a 3-year period. Notice that in the chart, the number of children with each disability corresponds more or less to the relative importance that we give to each disability in this book. In certain cases we have made exceptions. For example, few persons with leprosy have come to PROJIMO. But we have included a long chapter on leprosy because we realize it is a big problem in some places.

Clearly you cannot solve every problem. But there is much you can do. By asking questions, carefully examining the child, and using whatever information and resources you can find, you may be able to learn much about what these children need and to figure out ways to help them manage better.

|

![]()

| A8 | |

HOW COMMON ARE DIFFERENT DISABILITIES |

|

|

|

The little 'stick people' in this chart show how

many children might have each disability in an average group of

100 significantly disabled village children. These figures are

based on records of 700 children seen at PROJIMO, Mexico

(1982-1985), and other studies. The numbers in your area may be

similar or very different from these, depending on local

factors.

Note: Seeing and hearing disabilities, fits, and developmental delay are listed in 2 places, depending on whether they are the main disability or occur in addition to some other disability.

|

![]()

| A9 | |

HOW THIS BOOK IS ORGANIZEDThis book is divided into 3 parts: 1, "Working with the Child and Family," 2, "Working with the Community," and 3, "Working in the Shop." The disabilities that villagers usually consider most important are discussed in early chapters, beginning with Chapter 7. In many countries, more than half of the disabled children have either polio or cerebral palsy. For this reason, we start with them. Other disabilities are arranged partly in order of their relative importance, and partly to place near to each other those disabilities that are similar, related, or easily confused. Notice that in the chart on Page A8, certain 'secondary disabilities' occur very often. ('Secondary disabilities' are problems that result after the main disability.) For example, contractures (joints that no longer straighten) can develop with many disabilities. In many villages, there will be more children who have contractures than who have any single primary disability. For this reason we include some of the important secondary problems in separate chapters. Common disabilities that are often 'secondary' to other disabilities include: Contractures, Chapter 8 Dislocated Hips (either a primary or secondary disability), Chapter 18 Spinal Curve (either primary or secondary), Chapter 20 Pressure Sores (often occurs with spinal cord injury, spina bifida, or leprosy), Chapter 24 Urine and Bowel Management (with spinal cord injury and spina bifida), Chapter 25 Behavior Disturbances, Chapter 40 Other disabilities that are often the primary problem but commonly occur with other disability-usually with cerebral palsy-include fits (Chapter 29), blindness (Chapter 30), and deafness and speech problems (Chapter 31 ).

|

![]()

| A10 | |||

Note to

|

|||

| A11 | |||

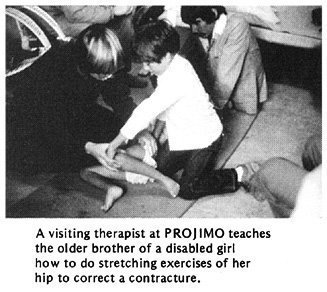

You rehabilitation professionals and

therapists can play an extremely important role in

'community-directed rehabilitation'. By simplifying and

sharing your knowledge and skills, you can reach many more

children. But to do this you will need to go out of the large

city rehabilitation centers and into neighborhoods and

villages. You will need to meet and work with the people on

their terms, as learners, teachers, and information providers.

You can help disabled persons, parents, and other concerned

individuals to organize small, community-directed centers or

programs. You can teach those who have the most interest to

become teachers. You can help local craftspersons to figure

out or improve low-cost designs for rehabilitation aids (and

they can help you). You can encourage village leaders to

improve paths and entrances to schools and public places. You

can help local people to understand basic principles and to

avoid common mistakes, so that they can be more effective

leaders and participants in home and community rehabilitation.

Whenever possible, arrange for village workers to learn to use this book with guidance from experienced rehabilitation workers. Those rehabilitation workers should be able to listen to the people, respect their ideas, and relate to them as equals.

|

![]()

| A12 | ||||||||

NOTE ON LANGUAGE USED IN THIS BOOK

In short, disabled

boys often receive better attention than do disabled

girls. This, of course, is not surprising: in

most countries, non-disabled boys also get better

treatment, more food, and more opportunities than do

non-disabled girls. |

Most literature on disabled children speaks of the disabled child as 'he'- This is partly because male dominance is built into our language. However, we feel this can only add to the continued neglect of the so-called 'weaker sex'. In this book, therefore, we have made an effort to be fair. But rather than to always speak of the child as 'he-or-she' or 'they', which is awkward, we sometimes refer to her as 'she' and sometimes as 'he'. If at times this is confusing, please pardon us. And

if we sometimes slip and give more prominence to 'he'

than 'she', either in words or pictures, please

criticize but forgive us. We too are products of our

language and culture. But we are trying to change.

|

|||||||

FOR MANY DISABILITIES IT IS VERY IMPORTANT THAT YOU READ

INFORMATION FROM SEVERAL CHAPTERS.

FOR MANY DISABILITIES IT IS VERY IMPORTANT THAT YOU READ

INFORMATION FROM SEVERAL CHAPTERS.