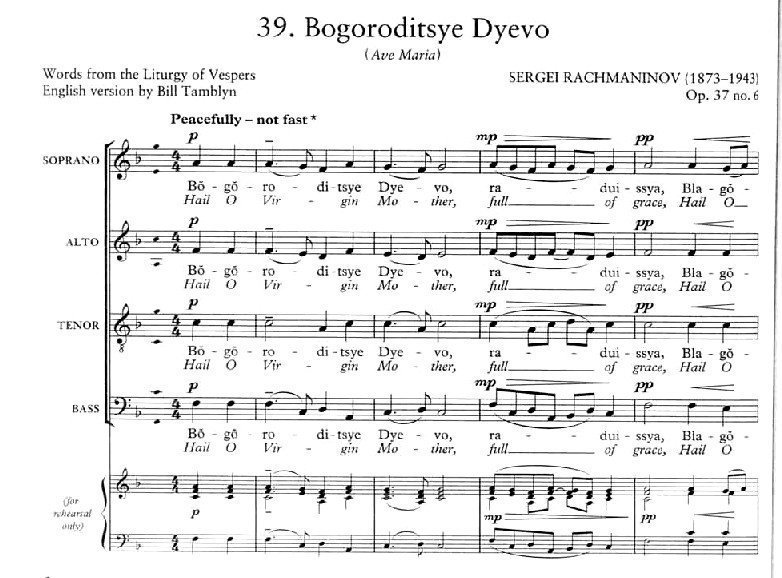

Bogoródyitse Dyévo (Ave Maria) Op.37-6

Composer: Sergey Rachmaninov (1873-1943), 1915

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sergey |

|

Rachmaninov |

|

1873 |

1943 |

|

1915 |

|

Op.37/6 |

Vespers, Bogoroditse Devo (Ave Maria) |

SATB |

a cappella |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sergey |

|

Rachmaninov |

|

1873 |

1943 |

|

1915 |

|

Op.37/15 |

Vespers, To the Mother of God |

SATB |

a cappella |

|

play/stop MIDI:

|

| Lyrics: |

|

Bogoródyitse Dyévo,

ráduisya,

Blagodátnaya Maríye,

Gospóď s Tobóyu.

Blagoslovyéna Ty v zhenákh,

i blagoslovyén Plod

chryéva Tvoyegó,

yáko Spása rodyilá

yesí dush náshikh. |

Rejoice,

O Virgin Mother Of God,

Mary full of grace,

the Lord is with You.

Blessed are You among women,

and blessed

is the Fruit of Your womb,

for You have borne

the Savior of our souls. |

| Recordings: |

Recording: Ave

Maria on website Nationskören UMEĹ |

|

|

play/stop MP3 sample:

Vĺrkonserten i Stadskyrkan 11/5 2004 |

| Score: available on

www.cpdl.org and

IMSLP |

|

|

| Internet

references, biography information. |

|

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sergei_Rachmaninoff

|

|

Sergei Vasilievich

Rachmaninoff (Russian: Серге́й Васи́льевич Рахма́нинов;[1] Russian

pronunciation: [sʲɪrˈɡʲej rɐxˈmanʲɪnəf]; 1 April [O.S. 20 March] 1873 – 28

March 1943) was a Russian[2] composer, pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff

is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a

composer, one of the last great representatives of Romanticism in Russian

classical music.[3] Early influences of Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, and

other Russian composers gave way to a thoroughly personal idiom that

included a pronounced lyricism, expressive breadth, structural ingenuity,

and a tonal palette of rich, distinctive orchestral colors.[4] The piano is

featured prominently in Rachmaninoff's compositional output. He made a point

of using his own skills as a performer to explore fully the expressive

possibilities of the instrument. Even in his earliest works he revealed a

sure grasp of idiomatic piano writing and a striking gift for melody.

Life

Childhood and youth

Rachmaninoff at the piano, in the early 1900s, before he graduated from the

Moscow ConservatoryThe Rachmaninoff family was a part of an "old

aristocracy", where all of the attitude but none of the money remained. The

family, of Tatar descent, had been in the service of the Russian tsars since

the 16th century, and had strong musical and military leanings. The

composer's father, Vasily Arkadyevich (1841–1916), an amateur pianist and

army officer, married Lyubov Petrovna Butakova (1853–1929), gained five

estates as a dowry, and had three boys and three girls.[5] Sergei was born

on 1 April 1873 at the estate of Semyonovo, near Great Novgorod in

north-western Russia.[6] When he was four, his mother gave him casual piano

lessons,[7] but it was his paternal grandfather, Arkady Alexandrovich, who

brought Anna Ornatskaya, a teacher from Saint Petersburg, to teach Sergei in

1882. Ornatskaya remained for "two or three years", until Vasily had to

auction off their home due to his financial incompetence—the five estates

had been reduced to one; he was described as "a wastrel, a compulsive

gambler, a pathological liar, and a skirt chaser"[8][9]—and they moved to a

small flat in Saint Petersburg.[10]

Ornatskaya returned to her home, and arranged for Sergei to study at the

Saint Petersburg Conservatory, which he entered in 1883, at age ten. That

year his sister Sofia died of diphtheria, and his feckless father left the

family, with their approval, for Moscow.[5] Sergei's maternal grandmother

stepped in to help raise the children, especially focusing on their

spiritual life. She regularly took Sergei to Russian Orthodox services,

where he was first exposed to the liturgical chants and the church bells of

the city, which would later permeate many of his compositions.[10] Another

important musical influence was his sister Yelena's involvement in the

Bolshoi Theater. She was just about to join the company, being offered

coaching and private lessons, but she fell ill and died of pernicious anemia

at the age of 18. As a respite from this tragedy, grandmother Butakova

brought him to a farm retreat on the Volkhov River, where he had a boat and

developed a love for rowing.[5] Having been spoiled in this way by his

grandmother, he became lazy and failed his general education classes,

altering his report cards, in what Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov would later call

a period of "purely Russian self-delusion and laziness."[11]

In 1885, back at the Conservatory, Sergei played at important events often

attended by Grand Duke Konstantin and other important people, but he failed

his spring academic examinations and Ornatskaya notified his mother that his

admission might be revoked.[5] Lyubov consulted with her nephew (by

marriage) Alexander Siloti, already an accomplished pianist studying under

Franz Liszt. After appraising his cousin's pianism and listening skills,

Siloti recommended that Sergei attend the Moscow Conservatory to study with

his own original teacher and disciplinarian, Nikolai Zverev.[12][13]

Graduation

While living with the Satins, Rachmaninoff (standing, second from left)

would vacation at Ivanovka, their summer house. He would marry his cousin

Natalia Satina (sitting, second from left).Neighboring families would come

to visit, and Rachmaninoff would find his first romance in the Skalon

family, with Vera, the youngest of three daughters. The mother would have

none of that, and he was forbidden to write to her, so he corresponded with

her older sister, Natalia, and from these letters much information about his

early compositions can be extracted.[12] In the spring of 1891, he took his

final piano examination at the Moscow Conservatory and passed with honors.

He moved to Ivanovka with Siloti, and composed some songs and began what

would become his Piano Concerto No. 1 (Op. 1). During his final studies at

the Conservatory he completed Youth Symphony, a one-movement symphonic

piece, Prince Rostislav, a symphonic poem, and The Rock (Op. 7), a fantasia

for orchestra.[5]

He gave his first independent concert on 11 February 1892, premiering his

Trio élégiaque No. 1, with violinist David Kreyn and cellist Anatoliy

Brandukov. He performed the first movement of his first piano concerto on 29

March 1892 in an over-long concert consisting of entire works of most of the

composition students at the Conservatory.[14]

His final composition for the Conservatory was Aleko, a one-act opera based

on the poem The Gypsies by Alexander Pushkin, which Rachmaninoff completed

while staying with his father in Moscow.[15] It was first performed on 19

May 1892, and although he responded with a pessimistic, "the opera is sure

to fail," it was so successful, the Bolshoi Theater agreed to produce it,

starring Feodor Chaliapin.[12] It gained him the Great Gold Medal, awarded

only twice before (to Sergei Taneyev and Arseny Koreshchenko[16]), and has

since had many more productions than his later works, The Miserly Knight

(Op. 24, 1904) and Francesca da Rimini (Op. 25, 1905). The Conservatory

issued him a diploma on 29 May 1892, and now, at the age of 19, he could

officially style himself "Free Artist."[5]

Rachmaninoff continued to compose, publishing at this time his Six Songs

(Op. 4) and Two Pieces (Op. 2). He spent the summer of 1892 on the estate of

Ivan Konavalov, a rich landowner in the Kostroma Oblast, and moved back with

the Satins in the Arbat District.[5] His publisher was slow in paying, so

Rachmaninoff took an engagement at the Moscow Electrical Exhibition, where

he premiered his landmark Prelude in C-sharp minor (Op. 3, No. 2).[17] This

small piece, part of a set of five pieces called Morceaux de fantaisie, was

received well, and is one of his most enduring pieces.[18][19]

He spent the summer of 1893 in Lebedyn with some friends, where he composed

Fantaisie-Tableaux (Suite No. 1, Op. 5) and his Morceaux de salon (Op.

10).[20] At the summer's end, he moved back to Moscow, and at Sergei

Taneyev's house discussed with Tchaikovsky the possibility of his conducting

The Rock at its premiere. However, because it had to be premiered in Moscow,

not Europe, where Tchaikovsky was touring, Vasily Safonov conducted it

instead, and the two met soon after for Zverev's funeral. Rachmaninoff had a

short excursion to conduct Aleko in Kiev, and on his return, received the

news about Tchaikovsky's unexpected death on 6 November 1893. Almost

immediately, on the same day, he began work on his Trio élégiaque No. 2,

just as Tchaikovsky had quickly written his Trio in A minor after Nikolai

Rubinstein's death.

Setbacks and recovery

The sudden death of Tchaikovsky in 1893 was a great blow to young

Rachmaninoff; he immediately began writing a second Trio élégiaque in his

memory, revealing the depth and sincerity of his grief in the music's

overwhelming aura of gloom.[21] His First Symphony (Op. 13, 1896) was

premičred on 28 March 1897 in one of a long-running series of "Russian

Symphony Concerts", but was brutally panned by critic and nationalist

composer César Cui who likened it to a depiction of the ten plagues of

Egypt, suggesting it would be admired by the "inmates" of a music

conservatory in hell.[22] The deficiencies of the performance, conducted by

Alexander Glazunov, were not commented on.[21] Alexander Ossovsky in his

memoir about Rachmaninoff[23] tells, first hand, a story about this

event.[24] In Ossovsky's opinion, Glazunov made poor use of rehearsal time,

and the concert program itself, which contained two other premičres, was

also a factor. Natalia Satina, later Rachmaninoff's wife, and other

witnesses suggested that Glazunov, who was by all accounts an alcoholic, may

have been drunk, although this was never intimated by Rachmaninoff.[25][26]

The failure of Symphony No. 1 (1897) long bothered Rachmaninoff. After the

poor reception of his First Symphony, Rachmaninoff fell into a period of

deep depression that lasted three years, during which he wrote almost

nothing. One stroke of good fortune came from Savva Mamontov, a famous

Russian industrialist and patron of the arts, who two years earlier had

founded the Moscow Private Russian Opera Company. He offered Rachmaninoff

the post of assistant conductor for the 1897–8 season and the cash-strapped

composer accepted. The company included the great basso Feodor Chaliapin who

would become a lifelong friend.[27] During this period he became engaged to

fellow pianist Natalia Satina whom he had known since childhood and who was

his first cousin. The Russian Orthodox Church and the girl's parents both

opposed their marriage and this thwarting of their plans only deepened

Rachmaninoff's depression.

In January 1900, Rachmaninoff and Chaliapin were invited to Yasnaya Polyana,

the home of writer Leo Tolstoy, whom Rachmaninoff greatly admired. That

evening, Rachmaninoff played one of his compositions, then accompanied

Chaliapin in his song "Fate", one of the pieces he had written after his

First Symphony. At the end of the performance, Tolstoy took the composer

aside and asked: "Is such music needed by anyone? I must tell you how I

dislike it all. Beethoven is nonsense, Pushkin and Lermontov also". (The

song "Fate" is based on the two opening measures of Beethoven's Fifth

Symphony.) As his guests were leaving, Tolstoy said: "Forgive me if I've

hurt you by my comments"; and Rachmaninoff graciously replied: "How could I

be hurt on my own account, if I was not hurt on Beethoven's?"; but the

criticism of the great author stung nevertheless.

In the same year, Rachmaninoff began a course of autosuggestive therapy with

psychologist Nikolai Dahl, who was himself an excellent though amateur

musician. Rachmaninoff began to recover his confidence and eventually he was

able to overcome his writer's block. In 1901 he completed his Piano Concerto

No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18 and dedicated it to Dr. Dahl. The piece was

enthusiastically received at its premiere at which Rachmaninoff was soloist

and has since become one of the most popular and frequently played concertos

in the repertoire. Rachmaninoff's spirits were further bolstered when, after

three years of engagement, he was finally allowed to marry his beloved

fiancée, Natalia. They were wed in a suburb of Moscow by an army priest on

29 April 1902, using the family's military background to circumvent the

church. The marriage was a happy one, producing two daughters: Irina, later

Princess Wolkonsky (1903-1969) and Tatiana Conus (1907-1961). Although

Rachmaninoff had an affair with the 22-year-old singer Nina Koshetz in

1916,[28] his and Natalia's union lasted until the composer's death. Natalia

Rachmaninova died in 1951.

After several successful appearances as a conductor, Rachmaninoff was

offered a job as conductor at the Bolshoi Theatre in 1904, although

political reasons led to his resignation in March 1906, after which he

stayed in Italy until July. He spent the following three winters in Dresden,

Germany, intensively composing, and returning to the family estate of

Ivanovka every summer.[29]

Rachmaninoff made his first tour of the United States as a pianist in 1909,

an event for which he composed the Piano Concerto No. 3 (Op. 30, 1909) as a

calling card. These successful concerts made him a popular figure in

America; however, he was unhappy on the tour and declined requests for

future American concerts until after he emigrated from Russia in 1917.[29]

This included an offer to become permanent conductor of the Boston Symphony

Orchestra.[30]

The early death in 1915 of Alexander Scriabin, who had been his good friend

and fellow student at the Moscow Conservatory, affected Rachmaninoff so

deeply that he went on a tour giving concerts entirely devoted to Scriabin's

music. When asked to play some of his own music, he would reply: "Only

Scriabin tonight".

Emigration and career in the West

The 1917 Russian Revolution meant the end of Russia as the composer had

known it. Being of the Russian bourgeoisie, from this change followed the

loss of his estate, his way of life, and his livelihood. On 22 December

1917, he left Petrograd for Helsinki with his wife and two daughters on an

open sled, having only a few notebooks with sketches of his own compositions

and two orchestral scores, his unfinished opera Monna Vanna and Nikolai

Rimsky-Korsakov's opera The Golden Cockerel. He spent a year giving concerts

in Scandinavia while also laboring to widen his concert repertoire. Near the

end of 1918, he received three offers of lucrative American contracts.

Although he declined all three, he decided the United States might offer a

solution to his financial concerns. He departed Kristiania (Oslo) for New

York on 1 November 1918. Once there, Rachmaninoff quickly chose an agent,

Charles Ellis, and accepted the gift of a piano from Steinway before playing

40 concerts in a four-month period. At the end of the 1919–20 season, he

also signed a contract with the Victor Talking Machine Company. In 1921, the

Rachmaninoffs bought a house in the United States, where they consciously

recreated the atmosphere of Ivanovka, entertaining Russian guests, employing

Russian servants, and observing old Russian customs.[31]

Due to his busy concert career, Rachmaninoff's output as composer slowed

tremendously. Between 1918 and his death in 1943, while living in the U.S.

and Europe, he completed only six compositions. Aside from the need to spend

much time performing so as to support himself and his family, the main cause

was homesickness. It was during these years that he traveled the United

States as a touring pianist.[32] When he left Russia, it was as if he had

left behind his inspiration. His revival as a composer became possible only

after he had built himself a new home, Villa Senar on Lake Lucerne,

Switzerland, where he spent summers from 1932 to 1939. There, in the comfort

of his own villa, which reminded him of his old family estate, Rachmaninoff

composed the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, one of his best known works,

in 1934. He went on to compose his Symphony No. 3 (Op. 44, 1935–36) and the

Symphonic Dances (Op. 45, 1940), his last completed work. Eugene Ormandy and

the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered the Symphonic Dances in 1941 in the

Academy of Music.

In late 1940 or 1941 he was approached by the makers of the British film

Dangerous Moonlight to write a short concerto-like piece for use in the

film, but he declined. The job went to Richard Addinsell and the

orchestrator Roy Douglas, who came up with the Warsaw Concerto.[33]

Sergei Rachmaninoff was also on the Board of Directors for the Tolstoy

Foundation Center in Valley Cottage, New York.

Friendship with Vladimir Horowitz

Vladimir Horowitz as he appeared at the time Rachmaninoff met himJust as the

Rachmaninoff household in the United States strove to reclaim the lost world

of pre-revolutionary Russia, Rachmaninoff also sought out the friendship and

company of some great Russian musical luminaries. In addition to Chaliapin,

he befriended pianist Vladimir Horowitz in 1928.

Arranged by Steinway artist representative Alexander Greiner, their meeting

took place in the basement of New York's Steinway Hall, on 8 January 1928,

four days prior to Horowitz's debut at Carnegie Hall playing the Tchaikovsky

First Piano Concerto. Referring to his own Third Piano Concerto,

Rachmaninoff said to Greiner he heard that "Mr. Horowitz plays my Concerto

very well. I would like to accompany him."[34]

For Horowitz, it was a dream come true to meet Rachmaninoff, to whom he

referred as "the musical God of my youth ... To think that this great man

should accompany me in his own Third Concerto ... This was the most

unforgettable impression of my life! This was my real debut!" Rachmaninoff

was impressed by his younger colleague. Speaking of Horowitz's

interpretation to Abram Chasins, he said "He swallowed it whole ... he had

the courage, the intensity, the daring."[34]

The meeting between composer and interpreter marked the beginning of a

friendship that continued until Rachmaninoff's death. The two were quite

supportive of each other's careers and greatly admired each other's work.

Horowitz stipulated to his manager that "If I am out of town when

Rachmaninoff plays in New York, you must telegraph me, and you must let me

come back, no matter where I am or what engagement I have." Likewise

Rachmaninoff was always present at Horowitz's New York concerts and was

"always the last to leave the hall."[35]

A Library of Congress photo of RachmaninoffNotably, the composer was present

at Carnegie Hall for Horowitz's American debut on 12 January 1928.

Recognizing the great pianistic ability, Rachmaninoff offered his friendship

and advice to Horowitz, telling him in a letter that "You play very well,

but you went through the Tchaikovsky Concerto too rapidly, especially the

cadenza."[35] Horowitz never agreed with the criticism of his tempo, and

retained his interpretation in future performances of the work.[35]

Rachmaninoff and Horowitz frequently performed two-piano recitals at the

composer's home in Beverly Hills. None of these performances, which included

the Second Suite and the two-piano reduction of the Symphonic Dances, were

recorded.

Rachmaninoff's faith in Horowitz's performances was such that, in 1940, with

the composer's consent, Horowitz created a fusion of the 1913 original and

1931 revised versions of his Second Piano Sonata.[36]

For Rachmaninoff, Horowitz was a champion of both his solo works and his

Third Concerto, about which Rachmaninoff remarked publicly after the 7

August 1942 Hollywood Bowl performance that "This is the way I always

dreamed my concerto should be played, but I never expected to hear it that

way on Earth."[35]

Illness and death

Rachmaninoff fell ill during a concert tour in late 1942 and was

subsequently diagnosed with advanced melanoma. His family was informed, but

he was not. On 1 February 1943 he and his wife became American citizens.[37]

His last recital, given on 17 February 1943 at the Alumni Gymnasium of the

University of Tennessee in Knoxville, included Chopin's Piano Sonata No. 2,

which contains the famous Marche funčbre (Funeral March). A statue called

"Rachmaninoff: The Last Concert", designed and sculpted by Victor Bokarev,

now stands in World Fair Park in Knoxville as a permanent tribute to

Rachmaninoff. He became so ill after this recital that he had to return to

his home in Los Angeles.[38]

Rachmaninoff died of melanoma on 28 March 1943, in Beverly Hills,

California, just four days before his 70th birthday. A choir sang his All

Night Vigil at his funeral. He had wanted to be buried at the Villa Senar,

his estate in Switzerland, but the conditions of World War II made

fulfilling this request impossible.[39] He was therefore interred on 1 June

in Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York.[5]

Works

The cadenza of Piano Concerto No. 3 is famous for its large chords.Main

article: List of compositions by Sergei Rachmaninoff

Rachmaninoff wrote five works for piano and orchestra—four concertos plus

the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. Of the concertos, the Second and Third

are the most popular.[40] He also wrote three symphonies, and his other

orchestral works include The Rock (Op. 7), Caprice bohémien (Op. 12), The

Isle of the Dead (Op. 29), and the Symphonic Dances (Op. 45).

Works for piano solo include 24 Preludes traversing all 24 major and minor

keys: Prelude in C-sharp minor (Op. 3, No. 2) from Morceaux de fantaisie

(Op. 3); ten preludes in Op. 23; and thirteen in Op. 32. Especially

difficult are the two sets of Études-Tableaux, Op. 33 and 39, which are very

demanding study pictures. Stylistically, Op. 33 hearkens back to the

preludes, while Op. 39 shows the influences of Scriabin and Prokofiev. There

are also the Six moments musicaux (Op. 16), the Variations on a Theme of

Chopin (Op. 22), and the Variations on a Theme of Corelli (Op. 42). He wrote

two piano sonatas, both of which are large scale and virtuosic in their

technical demands. Rachmaninoff also composed works for two pianos, four

hands, including two Suites (the first subtitled Fantasie-Tableaux), a

version of the Symphonic Dances (Op. 45), and an arrangement of the C-sharp

minor Prelude, as well as a Russian Rhapsody, and he arranged his First

Symphony (below) for piano four-hands. Both these works were published

posthumously.

Rachmaninoff wrote two major a cappella choral works—the Liturgy of St. John

Chrysostom and the All-Night Vigil (also known as the Vespers). It was the

fifth movement of All-Night Vigil that Rachmaninoff requested to have sung

at his funeral. Other choral works include a choral symphony, The Bells, the

cantata Spring, the Three Russian Songs and an early Concerto for Choir (a

cappella).

He completed three operas, all short: Aleko (1892), The Miserly Knight

(1903), and Francesca da Rimini (1904). He started three others, notably

Monna Vanna, based on a work by Maurice Maeterlinck; copyright in this had

been extended to the composer Février, and, though the restriction did not

pertain to Russia, Rachmaninoff dropped the project after completing Act I

in piano vocal score in 1908; this act was orchestrated in 1984 by Igor

Buketoff and performed in the U.S. Aleko is regularly performed and has been

recorded complete at least eight times, and filmed. The Miserly Knight

adheres to Pushkin's "little tragedy". Francesca da Rimini exists somewhat

in the shadow of the familiar, though entirely different, Zandonai opera of

that name.

His chamber music includes two piano trios, both which are named Trio

Elégiaque (the second of which is a memorial tribute to Tchaikovsky), and a

Cello Sonata. In his chamber music, the piano tends to be perceived by some

to dominate the ensemble. He also composed many songs for voice and piano,

to texts by A. N. Tolstoy, Pushkin, Goethe, Shelley, Hugo and Chekhov, among

others. Among his most popular songs is the wordless Vocalise.

Compositional style

Rachmaninoff with a piano scoreRachmaninoff's style showed initially the

influence of Tchaikovsky. Beginning in the mid-1890s, his compositions began

showing a more individual tone. His First Symphony has many original

features. Its brutal gestures and uncompromising power of expression were

unprecedented in Russian music at the time. Its flexible rhythms, sweeping

lyricism and stringent economy of thematic material were all features he

kept and refined in subsequent works. After the three fallow years following

the poor reception of the symphony, Rachmaninoff's style began developing

significantly. He started leaning towards sumptuous harmonies and broadly

lyrical, often passionate melodies. His orchestration became subtler and

more varied, with textures carefully contrasted, and his writing on the

whole became more concise.[41]

Especially important is Rachmaninoff's use of unusually widely spaced chords

for bell-like sounds: this occurs in many pieces, most notably in the choral

symphony The Bells, the Second Piano Concerto, the E flat major Étude-Tableaux

(Op. 33, No. 7), and the B-minor Prelude (Op. 32, No. 10). "It is not enough

to say that the church bells of Novgorod, St Petersburg and Moscow

influenced Rachmaninov and feature prominently in his music. This much is

self-evident. What is extraordinary is the variety of bell sounds and

breadth of structural and other functions they fulfil."[42] He was also fond

of Russian Orthodox chants. He uses them most perceptibly in his Vespers,

but many of his melodies found their origins in these chants. The opening

melody of the First Symphony is derived from chants. (The opening melody of

the Third Piano Concerto, on the other hand, is not derived from chants;

when asked, Rachmaninoff said that "it had written itself".)[43]

Rachmaninoff's frequently used motifs include the Dies Irae, often just the

fragments of the first phrase. Rachmaninoff had great command of

counterpoint and fugal writing, thanks to his studies with Taneyev. The

above-mentioned occurrence of the Dies Irae in the Second Symphony is but a

small example of this. Very characteristic of his writing is chromatic

counterpoint. This talent was paired with a confidence in writing in both

large- and small-scale forms. The Third Piano Concerto especially shows a

structural ingenuity, while each of the preludes grows from a tiny melodic

or rhythmic fragment into a taut, powerfully evocative miniature,

crystallizing a particular mood or sentiment while employing a complexity of

texture, rhythmic flexibility and a pungent chromatic harmony.[44]

A monument to Rachmaninoff in MoscowHis compositional style had already

begun changing before the October Revolution deprived him of his homeland.

The harmonic writing in The Bells (composed in 1913 but not published until

1920[45][46]) became as advanced as in any of the works Rachmaninoff would

write in Russia, partly because the melodic material has a harmonic aspect

which arises from its chromatic ornamentation.[47] Further changes are

apparent in the revised First Piano Concerto, which he finished just before

leaving Russia, as well as in the Op. 38 songs and Op. 39 Études-Tableaux.

In both these sets Rachmaninoff was less concerned with pure melody than

with coloring. His near-Impressionist style perfectly matched the texts by

symbolist poets.[48] The Op. 39 Études-Tableaux are among the most demanding

pieces he wrote for any medium, both technically and in the sense that the

player must see beyond any technical challenges to a considerable array of

emotions, then unify all these aspects[49]

The composer's friend, Vladimir Wilshaw, noticed this compositional change

continuing in the early 1930s, with a difference between the sometimes very

extroverted Op. 39 Études-Tableaux (the composer had broken a string on the

piano at one performance) and the Variations on a Theme of Corelli (Op. 42,

1931). The variations show an even greater textural clarity than in the Op.

38 songs, combined with a more abrasive use of chromatic harmony and a new

rhythmic incisiveness. This would be characteristic of all his later works —

the Piano Concerto No. 4 (Op. 40, 1926) is composed in a more emotionally

introverted style, with a greater clarity of texture. Nevertheless, some of

his most beautiful (nostalgic and melancholy) melodies occur in the Third

Symphony, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, and Symphonic Dances.[48]

Fluctuating reputation

Rachmaninoff monument, NovgorodHis reputation as a composer generated a

variety of opinions before his music gained steady recognition across the

world. The 1954 edition of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

notoriously dismissed Rachmaninoff's music as "monotonous in texture ...

consist[ing] mainly of artificial and gushing tunes" and predicted that his

popular success was "not likely to last".[50] To this, Harold C. Schonberg,

in his Lives of the Great Composers, responded, "It is one of the most

outrageously snobbish and even stupid statements ever to be found in a work

that is supposed to be an objective reference."[50]

The Conservatoire Rachmaninoff in Paris, as well as streets in Veliky

Novgorod (which is close to his birthplace) and Tambov, are named after the

composer. In 1986, Moscow Conservatory dedicated a concert hall on its

premises to Rachmaninoff, designating the 252-seat auditorium Rachmaninoff

Hall. A monument to Rachmaninoff was unveiled in Veliky Novgorod, near his

birthplace, as recently as 14 June 2009.

.../...

|

Please notify us of any

broken/defective links

Page last modified:

April 11, 2013

Return to my homepage:

www.avemariasongs.org

|

![]()