| 275

|

CHAPTER 44

Learning New Ways to Work

in the Non-Formal Economy

Work Opportunities for Survival in Hard Times

Every person has a right to contribute to their family, community, and

society as best they can. Human dignity and self-determination come, in

part, from being able to participate in functions that sustain and enhance

life. Life-enabling functions - in addition to acts of love, sharing, art,

and nurturing - also include productive and service-related activities

often referred to as "work." As our profit-hungry global economy

overshadows sustenance based on caring and sharing, more and more aspects

of production and service are performed as jobs for pay. Today's

money-minded value system - "You get what you pay for" - is systematically

marginalizing deeper human values, and the most vulnerable human beings.

Nevertheless, many life-sustaining human activities are still founded

on love and sharing. The majority of productive and service-providing work

is still done without pay, much of it by women and children in the home.

Many disabled people, too, find ways of contributing to the well-being of

family and community that are unpaid, yet life-affirming.

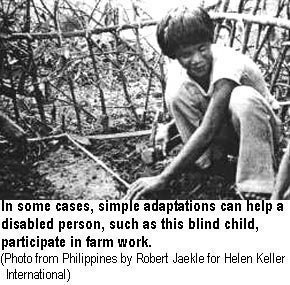

Rural areas. In traditional farming societies,

survival still largely depends on growing and gathering food, hauling

water and firewood, and other physical activities. So physical ability

tends to be highly valued (sometimes more than mental ability). In terms

of fitting into the life and production of the community in rural

areas, a child with a mental disability may be less socially handicapped

than is the child with a physical disability.

GOYO, a boy with Down's syndrome in Ajoya, the village

where PROJIMO is located, regularly went with his father to the fields.

Helping to plant and gather maize (corn) and to cut weeds was

repetitive work the boy could learn and do well. He took pride in helping

his family. During the long dry season when there was no farm work, Goyo

helped to earn a modest income for his family by hauling water from the

river for neighbors, in large tins on a donkey. Other boys disliked this

hard repetitive work, but Goyo did it with pride. Hauling water was his

livelihood until the village modernized and obtained a gasoline pump that

piped water into the homes.

|

| 276

|

| Urban areas. In cities,

successful integration into society often depends more on mental ability

than on physical fitness. Especially for the mentally slow child,

schooling may be a major hurdle. A youth who does not graduate finds it

hard to find a paying job, even doing physical labor. For these reasons,

although in rural areas more concern is often shown for people

with physical disabilities, in urban areas there tend to be more

programs for children who are mentally handicapped. In the

mushrooming cities of the world, unemployment is a growing

problem. Giant industries, in pursuit of "cost effectiveness"

(higher profits), are "down-sizing" (replacing workers with machines).

Today, so many persons are job-hunting that it is often hard for

disabled persons to compete. Since Mexico's entry into the international

free market economy, thousands of small businesses have closed down.

Even university graduates and licensed professionals - doctors, lawyers,

engineers - beg coins on street corners by selling trinkets or by

performing as fire-breathers and clowns.

In today's world of rising joblessness and falling wages, it may be

unrealistic to routinely train disabled people for jobs in the

formal economy. It often makes sense to help them learn skills

within the informal economy: producing things at home or in

neighborhood collectives that they can sell directly on the street or in

a stall at a community market.

Several rehabilitation programs that used to train disabled persons

for skilled factory jobs, such as operators of lathes and heavy

machinery, have changed their approach and now focus on teaching

disabled persons skills that enable them to be self-employed or to work

in small worker-run cooperatives.

Skills Training at PROJIMO

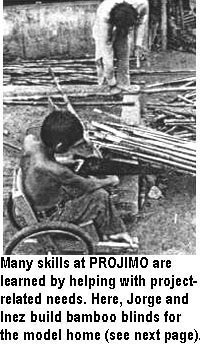

At PROJIMO, disabled persons are able to learn a variety of skills,

mostly in the form of apprenticeships, or learning by doing.

Some of these skills are related to providing health, medical, and

rehabilitation equipment and services to other disabled persons. Other

skills are learned as part of income-generating activities. These skills

range from the production of various articles for sale, to the

management of the village small-goods store, to running a modest welding

service or carpentry repair shop.

Income-generating activities at PROJIMO mostly

involve the production of low-cost items that can be made with low-cost

tools and equipment. Items include such things as:

| sandals and shoes, |

| ornaments for festivals, |

| woven rugs, |

| wooden toys and puzzles (see

pages 290-291 and

322), |

| leather belts with hand-stitched designs, |

| plastic-woven, metal-frame furniture. |

The production of these items serves three main purposes. 1)

It provides skills training and productive activities for the disabled

people involved. 2) It produces some income for the

program and modest wages for the disabled workers. 3)

It provides disabled persons with work experience, so that when they

return to their homes they can set up a small workshop there and help to

support themselves and their families. |

| 277

|

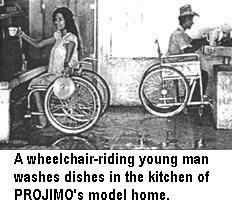

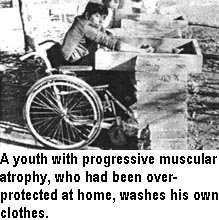

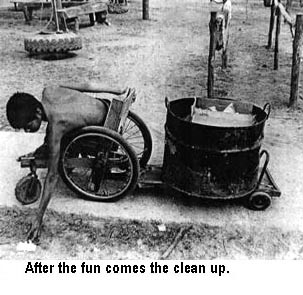

| Home-making skills.

PROJIMO provides an environment where young people can perform a variety

of home-making skills, ranging from cooking to

house-cleaning to laundry. Because the

disabled participants run the group kitchen, plan meals, and buy the

food, they acquire skills in home economics, learning by doing (and

learning from their mistakes). The Model Home, built

by disabled participants with help from the local community, is a

disability-adapted, low-cost, mud-brick building. It has many features

to help persons with different disabilities be able to keep house more

easily. Disabled persons who live temporarily in the model home while

visiting PROJIMO can try out its different features, and get ideas for

modifying their own houses. Adaptations range from a completely

wheelchair-accessible kitchen, to bedrooms with hand-grips hanging from

the ceilings for getting in and out of bed. Next to the model home is an

outdoor wheelchair-accessible laundry area.

Getting disabled boys and men to help wash dishes and clothes has

been a big challenge, but the adapted facilities make it easier.

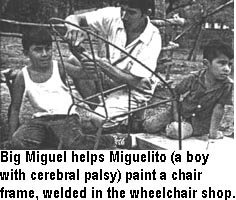

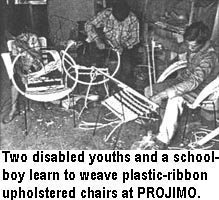

Skills learned in making assistive equipment can be applied to many

kinds of community work. On page 259, we

gave the example of how the wheelchair-making shop turned into a village

repair service where farmers came to repair their broken plows, and

children their busted bicycles. As another income-producing venture, the

workers in the welding shop began to make metal chair frames from metal

building rods (re-bar). Other disabled persons learned to weave the

chairs with plastic ribbon.

These woven chairs sold well in local villages. One boy, Rubén, later

set up his own chair-weaving business at his home, and soon earned twice

as much as his brother in a factory. |

| 278

|

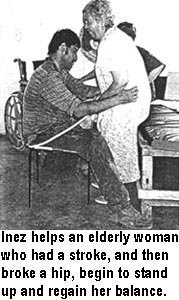

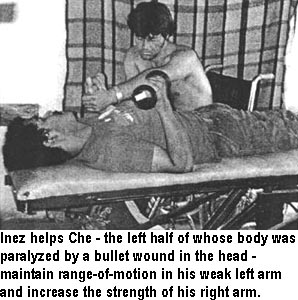

| Disabled people helping one

another provide a lot of the skills-learning at PROJIMO. Some

young persons who first came for their own rehabilitation have stayed on

at PROJIMO to learn the craft, organizational and rehabilitation skills

that most interest them. Several have become very capable

therapy-workers and craftspersons. One example is INEZ,

who first came as an abandoned street child, with one leg paralyzed by

polio. Inez has become a skilled therapy worker, having been taught by

visiting physical therapists.

(See story, page 253.)

(See story, page 253.)

Inez became such a capable therapist and rehabilitation worker that,

after a few years at PROJIMO, he set up his own successful physiotherapy

practice in the city of Mazatlán. In time, however, he gave up the

private practice and returned to PROJIMO. He preferred working as part

of a community-based team to help those with limited resources. Inez

married another PROJIMO worker, Cecilia, and has two energetic

daughters.

With a disabled child on his shoulders, Inez raises his crutches in a

sign of victory. This scene is from a village theater skit to raise

public awareness about the potential of disabled persons. It portrays

Inez's own story: how he first came to PROJIMO as a boy for

rehabilitation, and later became a skilled therapist helping others. |

| 279

|

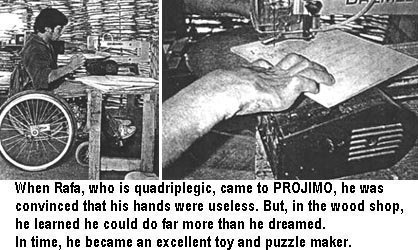

Carpentry skills.The PROJIMO

wood-working shop is where many disabled youth apprentice in

making all kinds of equipment for disabled children, ranging from

special seating and standing frames to educational toys. With the skills

learned in this shop, some of the disabled young people have gone on to

set up their own carpentry shops. Others have joined rehabilitation

programs where they can put both their carpentry and rehabilitation

skills to good use.

|

Marielos, who is paraplegic, makes a special standing frame for a

child, who watches with interest from his mothers arms. Marielos

also makes doll-house furniture, for which she has more requests for

sales than she can meet. |

Mario, a street youth who became paraplegic from a bullet wound

in the spine, learned carpentry skills while helping to make special

seating and other equipment at PROJIMO. |

But what makes Mario an outstanding worker is his heartfelt

understanding and concern for the children he works with (see

page 270-271). Here, he adapts a

support for a girl whose leg is casted. |

Even some of the young people who are quadriplegic (with paralysis of

their arms and hands as well as legs) have become skillful carpenters

and toy makers, The first obstacle for them to overcome is their feeling

(and fear) of incapacity. The beauty of PROJIMO is that new-comers have

excellent role models to follow. They dare to try new things and to test

- and stretch - their limits.

|

| 280

|

|

| Business skills. Several

disabled persons at PROJIMO who collectively run the program have

also learned some organizational skills, and also

book-keeping. Conchita studied accounting before

she became paraplegic. Now she is a coordinator of the program and

manages the financial records. She has taught other workers to help

with accounting and program records. These skills can be useful for

those who later set up their own small workshops or cooperatives.

Video skills. Some work opportunities are

unplanned. The PROJIMO team decided they should make educational

video-tapes of aspects of rehabilitation and therapy where movement

is important, and where words and drawings are not sufficient. So

they raised money to buy a video camera and recruited a skilled

filmmaker to come teach them how to use the equipment, and put

together and edit a film. Mari and Conchita, the two main

coordinators of PROJIMO, mastered these skills. |

|

| Conchita Lara, with Mario's help, works on the

monthly financial report of PROJIMO. For more about Conchita, see

Chapter 42. |

Video cameras and film making was a new and exciting event for the local

villagers. There are 3 or 4 video cassette players in town. Local people

begged to have pictures taken of themselves and their families. Having

acquired the needed skills, Conchita and Mari soon found themselves

invited to take videos of events such as baptisms, weddings, and the

coming-of-age parties of 15-year-old girls.

Making and editing of videos has become one of the more

successful income-generating activities of PROJIMO. |

| 281

|

Maintaining PROJIMO's grounds and buildings.

The maintenance of PROJIMO provides skills training and practice at a

range of tasks useful for maintaining a home or business.

|

Cecilia, who is now married and runs her own household, helps to

clean up PROJIMO's consultation room. |

Heliodoro, who is paraplegic, helps Inez repair the project water

pump, and in the process he learns a useful skill. |

A schoolboy helps Jesús, who is almost blind, to paint the swings

in PROJIMO's Playground for All Children. (See more on Jesús in

Chapters 16 and

45.) |

|

| 282

|

The Spanish Language Training Program run by disabled villagers.

For persons whose disabilities extensively limit the use of their

bodies and hands, finding work opportunities can be quite a challenge.

This is especially true for those who have little or no formal education

- which is often the case.

One skill such persons do have in Mexico is speaking Spanish. So the

PROJIMO team decided to start an intensive Spanish language training

program. For the first classes they invited foreign students who, in

exchange for being taught conversational Spanish, would help teach their

teachers how to teach. PROJIMO especially welcomes language students who

are disabled activists, rehabilitation workers, or progressive health

workers. (If you are interested, send for a brochure. Fees are modest

and help support the program.)

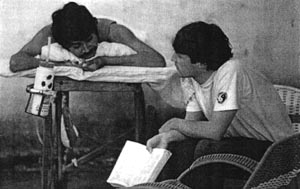

Quique, who was quadriplegic, had almost no control of his hands. He

was one of the teachers in the Intensive Spanish Language Training

Program. Here, he is teaching an idealistic young North American

physiotherapist. He is lying on a wheeled cot, or gurney, to allow the

pressure sores on his backside to heal.

VICTOR, a young doctor, gave PROJIMO one of its

biggest rehabilitation challenges. Soon after graduating from medical

school, Victor broke his neck in a car accident. He spent months in a

hospital, where he developed pressure sores and urinary infections. He

had become suicidal. He was sure he could never work as a doctor.

At PROJIMO, Victor gave the village team a hard time. He did not

believe that a group of uneducated villagers - disabled ones at that -

could do anything for him. But, little by little, his sores healed and

his health improved. He learned to use his hands to grip things by

bending his wrists backwards. In time, he started to provide medical

services to sick villagers. Victor became one of the exceptional doctors

in Mexico who choose to work in a poor and rural community. (In Mexico

City there are over 5000 unemployed doctors who refuse to go to the poor

rural areas where they are needed.) |

| 283

|

ALL WORK AND NO PLAY MAKES JUÁN A DULL BOY

Note: The different work activities shown in this

chapter represent only a few of many possibilities. We have focused on

some of the more innovative examples, mostly from PROJIMO. Clearly, the

examples shown here only touch the surface of what is possible.

|

| 284

|

A Time for Play and a Time for Work

|

|