| 295

|

CHAPTER 45

From Beneficiaries to Facilitators:

Ramona, Jesús, and Child-to-Child

Looking at Strengths, Not Weaknesses

One of the shortcomings of games that give non-disabled children a

temporary, imaginary disability (such as tying a stick to one leg) is that

it only allows them to experience the difficulties and frustrations of

being disabled, rather than to appreciate the ways that disabled persons

develop new strengths and abilities to cope with their difficulties. Thus,

the game can result in pity rather than appreciation.

To encourage a group of youngsters to focus on strengths rather than

weaknesses, it helps to include disabled children in the games.

The importance of this became clear during a Child-to-Child training

program held in Nicaragua in 1990.

RAMONA, a timid teenaged girl, was one of the disabled

participants. One of her legs was paralyzed and contracted from polio, and

she walked on the other leg using crutches. When the time came to play a

"simulation game" to help non-disabled youngsters to experience

disability, several children were asked to tie one foot to their backside

and to stand on one leg. Other children were asked to find a pole or

improvise crutches, so that their "disabled" playmates could walk. Then

they held a race. To everyone's surprise, Ramona shyly asked if she could

join the race.

Ramona, of course, won with flying colors. The other children, rather

than feeling sorry for her, marveled at her speed and agility.

This game was not only an eye-opener for the children, it was a

liberating experience and a turning point for Ramona. In the various

activities that followed, others treated her with new respect. And Ramona,

losing much of her shyness, participated enthusiastically.

Ramona has come a long way since then. As a health promoter with CISAS,*

she has become a leader in her community and a strong defender of women's

and children's rights. She traveled from Nicaragua to Mexico to take part

in a PROJIMO workshop on disability rights. (While there, the PROJIMO team

straightened her knee contracture with a series of plaster casts, then

made her a light-weight plastic brace.) Back in Nicaragua, Ramona has

formed and leads an organization of disabled persons. She has also become

an outstanding facilitator of Child-to-Child activities, in which she

helps young people in her town look at the strengths of disabled children,

not their weaknesses.

- _________________

- * CISAS is a Nicaraguan health education program that has done a lot

to promote Child-to-Child and human rights. See

p.341.

Fingers that see. At the same Child-to-Child workshop

in Nicaragua where Ramona won the race, other disabled children

participated. A blind girl showed other children how she could read

Braille (tiny raised dots on a page) with her fingertips (see

page 5). The other children were amazed at

her ability, especially when she explained how she did it and then had

them try it. Far from feeling pity, they marveled at and admired the blind

girl's ability. |

| 296

|

Classmates Help a Disabled Child to Stay in School

In January, 1995, PROJIMO hosted a four-day workshop on the

management of small community based programs. (Lack of management skills

is a common problem.) Participants came from 13 programs in Mexico and

Central America. Ramona, described above, came from Nicaragua. The

PROJIMO team was delighted to have her back.

JESÚS, one of the disabled children staying at

PROJIMO, rolled up to the study group in his wheelchair, interrupting a

lively workshop that was being held under a giant laurel tree. He asked

for Conchita, one of PROJIMO's coordinators who was participating in the

workshop. The 13-year-old was obviously distraught. "This is the last

day I'm going to school!" he declared.

"Why?" asked Conchita, rolling over to him in her own wheelchair.

"Because the teacher is mean to me," said Jesús. "When I ask her what

is written on the blackboard, she scolds me for disturbing the class!"

"Doesn't your teacher know you can't see?" asked one workshop

participant, herself blind.

"I've told her, but it's like she doesn't hear me. Or doesn't believe

me." said Jesús. "She treats me as if it were my fault I can't see!"

Jesús, who is multiply disabled, has had a hard life. He was born

with spina bifida, a defect of the spinal cord that causes reduced

strength and feeling in his lower body (see

page 131). With a lot of help from his parents, at age 3 Jesús did

learn to walk, although awkwardly. Then, when he was six, he fell ill

with meningitis. This left him nearly blind and with muscle stiffness

(spasticity) that reduced control of his movements. The stiffness

gradually lessened, and the boy learned to walk again, with crutches and

dragging his feet. But due to the lack of feeling in his feet, he

developed a deep sore on his right foot. This led to a chronic bone

infection and, at age 7, his right leg was amputated. Jesús went back to

crawling, and gradually developed flexion contractures of his hips and

remaining knee. From sitting too long on his buttocks (which also lacked

feeling), he developed large pressure sores, down to the bone. His lack

of urine and bowel control (due to spina bifida) made the sores hard to

keep clean, and they had worsened, year after year. (A device to help

heal the sores on Jesús' foot is described in

Chapter 16.

When Jesús was 13 years old, his mother brought him from their home

in the distant city of Mazatlán to PROJIMO, in the village of Ajoya. On

examining Jesús, the team told him that with an artificial leg - which

they could make - he could probably walk again. But first his hip and

knee contractures must be corrected. This, they explained, would require

weeks or even months of gradual stretching while lying on a wheeled cot,

or gurney. In any case, lying face-down would be necessary to allow his

large pressure sores to heal. Jesús was so eager to walk that he agreed.

His mother did, too. So plans were made for him to stay at PROJIMO for

an extended time.

While in Ajoya, Jesús had his first opportunity to attend school. His

excitement about school overcame his fear of being away from home. His

mother and older sister had already taught him the alphabet. He could

read the letters and numbers if they were drawn very large and if he

held them two or three inches from his face. So Jesús was enthusiastic

about learning more. At first he went to school on his wheeled gurney. |

| 297

|

| Jesús is obviously bright and has an

inquisitive mind. In spite of his poor vision, he learned so fast that,

within a few weeks, he was advanced to the 2nd grade. Unfortunately, his

new teacher had little understanding of his special needs. She regarded

the disabled child more as a nuisance than as a challenge. Because Jesús

was unable to read either the blackboard or his books, and because his

teacher scolded him when he asked for help, the boy had grown

discouraged. "It's no use," he complained. "I'm going to quit school. I

want to go home." When Jesús announced that he was quitting school,

the workshop participants tried to think of ways to help the boy find

the courage and will to continue. Three participants were from a program

for visually impaired persons, and one was blind herself. They suggested

ideas for helping Jesús learn more easily, and offered to talk with his

teacher.

Then Ramona from Nicaragua exclaimed, "Why don't we try a

Child-to-Child approach? It could help both the kids and teacher

understand his problem better and look for ways to assist him with his

studies?" The workshop participants knew little about Child-to-Child,

but wanted to learn more. Those working with blind persons were eager to

take part in Jesús' class. Arrangements were made with the school

Director and the second grade teacher to do the activity the next

afternoon.

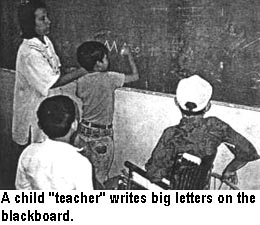

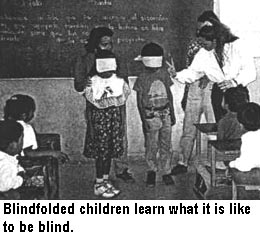

A Child-to-Child activity.

Ramona led the Child-to-Child activity. Her spritely manner at once

captured the children's attention. First she explained a bit about

Child-to-Child and introduced the visitors. Then she told the children

that she wanted to explore with them what it was like to be blind, or

partially blind, like Jesús. When she said this, all the children looked

at Jesús, who sat in his wheelchair at the side of the classroom.

Sensing their attention, he sat up importantly and smiled back at them.

Ramona called for volunteers to take part in a role play. Two

children played the role of blind pupils. Two others took turns playing

the role of a visually impaired pupil like Jesús. And two others played

the role of school teacher. The two "blind" children had bandanas tied

tightly over their eyes, and could see nothing. They tried to find their

way around the classroom and to follow the instructions of the

"teacher." These children bumped into things and got confused. They said

it was like trying to find their way in a dark room at night.

The other children helped by giving them clues or guiding them. They

also played a trick on one of the "blind" boys. The "teacher" asked the

boy to find a girl named Eliza and bring her to the front of the class.

Feeling his way, the boy made his way to Eliza's seat. But as he

approached, Eliza quickly swapped seats with the girl next to her. The

boy took the other girl by the hand, led her forward, and presented her

to the teacher. "Here she is," he said proudly. "Are you sure this is

Eliza?" asked the child playing the teacher. "Yes!" said the boy. "Take

off your blindfold and have a look," said the "teacher."

The boy took off the blindfold off and stared dumbfounded at the girl

he had thought was Eliza. "They tricked me!" he shouted. The class burst

into laughter.

|

| 298

|

|

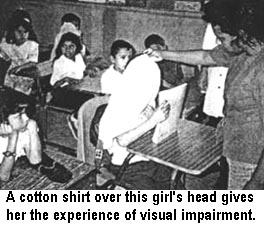

In the next role play, a pupil experienced

partial blindness: a cotton shirt was draped over her head.

(Ramona had tried different cloths until she found one that limited

vision similar to Jesús' visual loss.) The "teacher" then asked the

pupil to read from her book. Only by holding it close to her face could

she read the largest letters. Then the "teacher" wrote a word on the

blackboard, and said, "Read it." To read, the pupil had to go very close

to the blackboard. By making the letters bigger and bolder, the

weak-sighted child could read the word from farther away. But she still

had to go close to the blackboard.

After this role play with simulated visual impairment, another

"pretend teacher" asked Jesús to read a word on the blackboard. Jesús

rolled forward. To read the words he had to grip the armrests of his

wheelchair and lift himself upright so that his face was almost touching

the word, which he read proudly.

After the school children saw the difficulty Jesús had reading, both

from the blackboard and from his school books, Ramona asked them, "Can

you think of ways that you, Jesús' classmates, can help him understand

his lessons and get the most out of school, in spite of his disability?"

The children came up with a wide variety of creative

suggestions:

| Be sure that Jesús sits at the front of the class, near the

blackboard. |

| Write and draw very large on the blackboard. |

| Have Jesús sit next to a pupil who whispers in his ear what is

written on the blackboard. |

| Our teacher, or one of us, should always read out loud what is

written on the blackboard. |

| One of us could copy into Jesús' notebook what is written on the

blackboard. |

| And we should write in his notebook in big, dark, clear letters. |

| Maybe Jesús could use an extra-big notebook and a black marking

pen, so he can read for himself what he writes. |

| Would it help if Jesús had a magnifying glass? |

| We children could take turns after school, helping Jesús with his

homework and reading to him from his books. |

| Some of us can also take turns helping to bring him to and from

school. (Although Jesús has learned to find his way without trouble,

there is a steep slope on the way to school, and Jesús appreciates the

assistance and the camaraderie.)

|

|

| 299

|

|

With a little prompting, the children came up with yet more

ideas:

| What about a tape recorder? We could record the

lessons from his books, and that way he could study them whenever he

wants. |

| When we are given tests and exams, couldn't Jesús whisper the

answers in the teacher's ear? (In other words, take exams

orally.) |

After this discussion, Ramona asked the visually impaired visitor if

she had any further ideas. She suggested a way to make writing easier

for Jesús (and the results more legible for the teacher). They could

give Jesús writing paper with extra dark lines. A

visually impaired person simply cannot see the very thin pale lines on

ordinary lined paper. If paper with dark, thick, widely separated lines

could not be obtained, she suggested, the children could create such

paper for Jesús with a ruler and a marking pen.

Then the blind visitor made a suggestion that fascinated the class.

She told them that, with a little help, Jesús could learn to

read with his fingers. From her bag she pulled a large sheet of

Braille script, and showed the children how she could

read it with her finger tips (see p.5).

She let every child feel the tiny bumps on the paper. Then she let Jesús

try it, guiding his finger over the paper. She gave Jesús a sheet with

the Braille alphabet. Next to each Braille letter she printed a large

dark letter, so that Jesús could begin to learn Braille. The children

were fascinated, and Jesús was so excited he trembled. The visitor

explained that the Braille system had been invented many years ago by a

blind schoolboy in France.

Judging from the children's response, this Child-to-Child activity

was a big success. Jesús decided to stay in school. The teacher asked

Jesús to sit next to a mischievous boy who had made many suggestions of

ways to help Jesús with his learning. A few of his classmates began

accompanying Jesús to and from school. Some even helped him with his

homework. And now Jesús has both a magnifying glass and a small tape

recorder. A girl at PROJIMO, who also has spina bifida and an amputated

leg, offered to help tape his lessons.

Clearly, not all the problems are solved. Rather than helping Jesús

to do his homework himself, his helpers at first tended to do it for

him. But the whole Child-to-Child process has been a rewarding

experience for all. Both Jesús and his classmates are learning

more than just their lessons. They are learning the joy that comes from

bridging barriers to understanding, from creative problem-solving, and

from helping one another.

Jesús finished the school year in Ajoya, where he became more

self-confident and independent. His mother, who had previously been

reluctant to send him to school, was convinced he should continue.

Jesús, who had begun to learn Braille, was eager to learn more.

During the summer vacation, the PROJIMO team arranged for Jesús to study

Braille in Mazatlán with the help of a young man with muscular

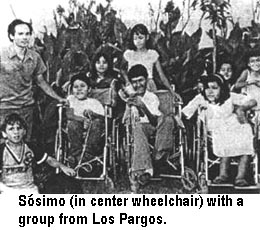

dystrophy, named SÓSIMO. Since he was a young child,

Sósimo had been active in Los Pargos, a program run by families of

disabled children (see Chapter 48).

Although his health was very delicate, Sósimo was still an active leader

of the program. He had studied Braille in order to teach blind children.

Jesús could not have had a better teacher - nor a better role model.

|

| 300

|

Jesús Becomes a Child-to-Child Facilitator

In spite of his early difficulties, after the Child-to-Child

experience, Jesús liked school so much that he chose to return to attend

school in Ajoya the following school year.

Jesús now helps to facilitate Child-to-Child activities in other

villages. His first involvement concerned a family from a village called

Limón, 50 kilometers away. The family had come to PROJIMO with two

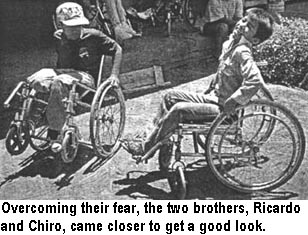

children, CHIRO and RICARDO, who had

muscular dystrophy (see page 317). The

brothers, ages 9 and 11, walked awkwardly and were very shy. Two years

before, their parents had tried sending them to school. But the boys no

longer attended because they had been teased by the other children.

The PROJIMO team thought that introducing Child-to-Child to the

school children in Limón might help. They invited Jesús to go with them.

He eagerly accepted.

Arriving at Limón, Jesús and the PROJIMO team first visited the

family of the two brothers, who rather reluctantly accompanied them to

the school. It was a tiny primary school with 3 rooms. The teachers were

intrigued by the arrival of the disabled troupe, and gladly interrupted

their classes.

Ricardo and Chiro watched from a safe distance. They were astonished

when Jesús ran in a wheelchair race with the most athletic children in

the class. Skilled in wheelchair use, the disabled youngster left his

competitors far behind. Excited, the brothers moved closer.

Having won the respect of the children by winning the race, Jesús did

"wheelies" (balancing on the chair's back wheels) and whirled in circles

on two wheels, gracefully dancing. The able-bodied riders tried to

imitate Jesús, with upsetting results. Everyone applauded Jesús, who

thrived on the attention.

After the activities, the PROJIMO team discussed with the class and

teacher the importance of treating disabled children as equals, and of

helping them to build on their strengths rather than pitying or teasing

them for their weaknesses. The school children appeared eager to

befriend and assist the two newcomers. And the brothers, after watching

the children's admiration for the blind boy in a wheelchair, lost some

of their fear of school. Arrangements were made for the boys to attend

school next term.

All benefitted from this experience - not least, Jesús. Not only did

he win admiration from his peers, but he discovered the joy of helping

other children with special needs to gain new self-confidence and hope. |

|