| 001

|

002

|

PART 1

WORKING WITH THE CHILD AND FAMILY

Information on different Disabilities

|

|

|

003 |

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION TO PART 1

Making Therapy Functional and Fun

|

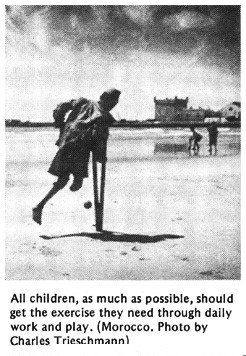

| Most disabled people in the

world live in villages and poor communities where they

never see a 'rehabilitation expert' or 'physical

therapist'. But this does not always mean that they have

no 'rehabilitation' or 'therapy'. In many villages and

homes, family members, local craftspersons, traditional

healers, and disabled people themselves have figured out

ways for persons with disabilities to do things better and

move about more easily. We have seen examples where

local carpenters, tinsmiths, leatherworkers or blacksmiths

have put together simple crutches, carts, wooden legs and

other aids. We know parents who have figured out ways of

adapting daily activities so that their children can help

do farm work or housework-and at the same time get much of

the exercise (therapy) they need.

|

| Two words often used

by people who work with disabled persons are

'rehabilitation' and 'therapy'.

Rehabilitation means

returning of ability, or helping a disabled

person to manage better at home and in the community.

Therapy basically means treatment.

Physical therapy-or physiotherapy-is the art

of improving position, movement, strength, balance,

and control of the body. Occupational therapy

is the art of helping a disabled person learn to do

useful or enjoyable activities.

We speak of 'therapy' as an art

rather than a science because there are many different

beliefs and approaches, and because the human feeling

that goes into therapy is as important as the methods.

|

|

| Sometimes the 'rehabilitation' that

families and communities figure out by themselves works

better in their situation than do methods or aids

introduced by outside professionals. Here are 2 examples: |

|

- In India, I met a villager who had lost a leg in a

house-building accident. Using his imagination, he had

made himself an artificial leg with a flexible foot out

of strong wire with strips of an old cotton blanket for

padding. After several months, he had the chance to go

to a city where a professional 'leg maker' (prosthetist)

made him a costly modern fiberglass leg. The man tried

using the new limb for a couple of months, but it was

heavy and hot. It did not let his stump breathe like his

'wire cage' leg. And he could not squat to eat or do his

toilet, as he could with his homemade leg. Finally, he

stopped using the costly new leg and went back to the

one he had made. For the climate and customs where he

lived, it was more appropriate.

- In a small village in Mexico, over the years, the

community together with its deaf citizens has developed

a simple but expressive 'sign language' using their

hands, faces, mouths, and whole bodies to communicate.

As a result, children who are born deaf quickly and

gracefully learn to express themselves. They are well

accepted in the community, and some have grown up to

become creative and respected craftspersons. This

village method of 'total communication' allows the deaf

children to learn a useful language more quickly,

easily, and effectively than does the 'lip reading and

speech' method now taught in the cities. For children

who are born deaf, attempts to teach only

lip-reading-and-spoken- language often end in cruel

disappointment (see Page 264).

The 'special educators' in the cities could

learn a lot from these villagers. |

|

004 |

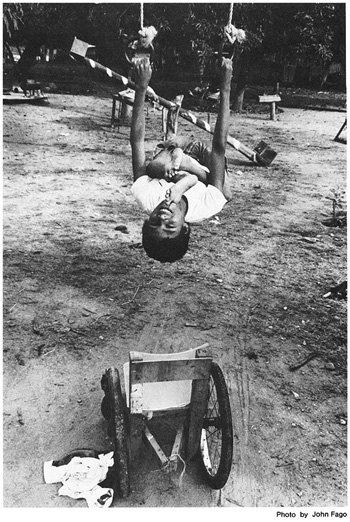

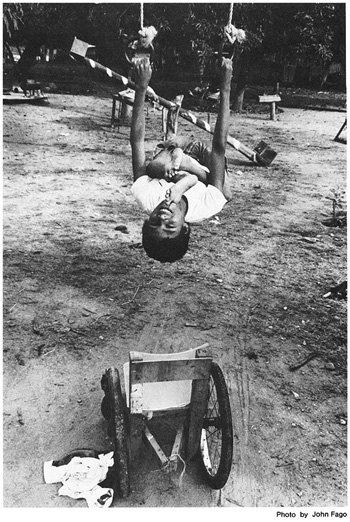

| Disabled children-if

allowed-often show great imagination and energy in

figuring out ways to move about, communicate, or get what

they need. Much of what they do is, in effect, 'therapy',

artfully adapted for and by each child. With a

little help, encouragement, and freedom, the disabled

child can often become her own best therapist.

One thing is certain: she will make sure her therapy is

'functional' (useful), always changing it to meet her

immediate needs. A disabled child, like other children,

instinctively knows that life is to be lived NOW and that

her body and her world are there to be explored, used, and

challenged. The best therapy is built into

everyday activities: play, work, relationship, rest, and

adventure.

The challenge, then, for health workers and parents (as

well as for therapists), is to look for ways that children

can get the 'therapy' they need in ways that are easy,

interesting, and functional.

This takes imagination

and flexibility on the part of all those working with

disabled children. But mostly, it takes understanding.

When family members clearly understand the reasons for

a particular therapy and the basic principles

involved, they can find many imaginative ways to do

and adapt that therapy. |

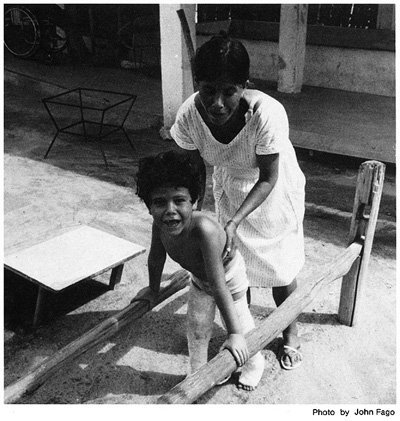

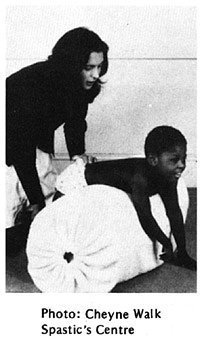

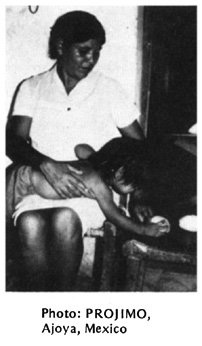

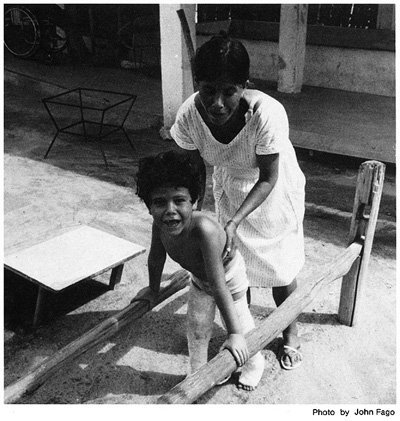

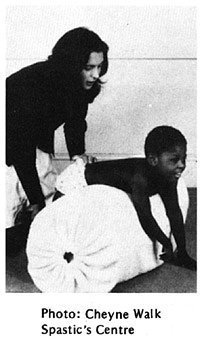

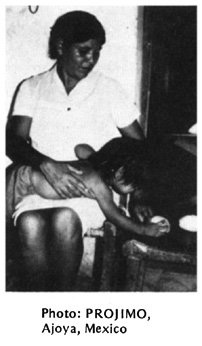

'Physical therapy' to

improve control of the head, strength of the back, and

use of both arms and hands together: |

| (a) in a city clinic |

(b) in a village home |

|

|

|

| Appropriate therapy helps the child to

enjoy himself, be useful, and take part with others,

while mastering the skills for daily living.

|

|

|

005 |

|

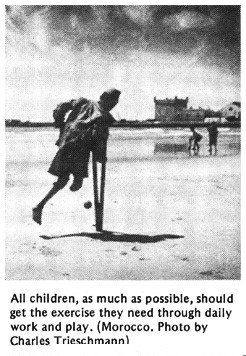

Physical therapy and rehabilitation

techniques have been developed mostly in cities. Yet most

of the world's disabled children live in villages and

farms. Their parents are usually very busy growing the

food and doing the chores to keep the family fed and alive

from day to day. In some ways, this makes home therapy

more difficult. But in other ways it provides a

wide range of possibilities for exciting therapy in which

the child and his family can meet life's needs together.

Here is a story that tells how therapy can

be adapted to village life.

|

|

|

Maricela lives in a small village on a river. She has

cerebral palsy. When she was 4 years old, she was just

beginning to walk. But her knees bumped together when she

tried to take steps. So she did not try often. Also, her

arms and hands were weak and did not work very well. |

| Her family saved money and

took Maricela to a rehabilitation center in the city.

After a long wait, a therapist examined her. He explained

that Maricela needed to stretch the muscles on the inner

side of her thighs, so her knees would not press together

as much. |

|

|

He recommended that her parents do

special exercises with her, and that they buy a special

plastic seat to hold her knees wide apart. |

|

|

He said she also needed exercises to

strengthen and increase the control of her hands and arms.

He suggested buying her some special toys, game boards,

and aids to practice handling and gripping things. |

|

|

Maricela's family could not afford these

costly things. So back in her village her father used

whatever he could find to make similar aids at low cost.

First he made a special seat of sticks. |

|

|

Later he made a better seat with pieces

of wood, and an old bucket to hold her legs apart. |

|

|

Then, using a board, corn cobs and rings

cut from bamboo, he added a small table so that she could

play games to develop hand control. |

|

|

He also made a hand exerciser out of

bamboo. |

|

At first, while they were strange and new, Maricela used

her special seat and played with her special toys. But

soon, she got bored and stopped using them. She wanted to

do the things that other children did. She wanted to go

with her father and brother to the cornfield. She wanted

to help her mother prepare food and wash the clothes. She

wanted to be helpful and grown up.

|

|

006

|

|

|

So she broke her special toys

and refused to sit in her special seat. Her parents were

furious with her-and she loved it! She would sit for hours

with her knees together and her legs bent back. Walking

began to get more difficult for her, so she did not walk

much.

|

|

Her parents then visited a small

rehabilitation center in a neighboring village. The

village team suggested that they look for new ways to help

Maricela keep her knees apart and improve control of her

arms and hands-ways that would be exciting and help her to

develop and practice useful skills together with the rest

of her family. Here are some of the ideas that Maricela

and her parents came up with: |

|

|

When she was good (and sometimes even if

she was not) her father would let her help shell corn with

him and the other children. Because she had trouble

holding the corn and snapping off the grain with her

fingers, her father made a special holder and scraper. |

|

|

The basket between her legs held her

knees apart, and the shelling of the corn strengthened her

arms, gave her practice gripping, and improved her

coordination and control. It was hard, important work

that Maricela found she could do. And she loved it! |

|

|

Maricela's mother sometimes invited her

to help wash the clothes at the river. Maricela would sit

at the river's edge with a big ' washing rock' between her

legs. She would wash the clothes by squeezing and beating

them against the rock- just like her mother. The rock

kept her knees apart and the squeezing and banging

strengthened her hands and improved her control. But what

mattered was getting the clothes clean. it was hard work.

But she found it easy-and fun! |

|

|

Coming back from the river, Maricela just

had to walk. It was too far to crawl. And besides, she had

to help her mother carry back the washed clothes. This was

hard, but she tried hard, and could do it! Carrying the

pails of clothes helped her learn to walk without bending

and jerking her arms so much.

|

|

|

To help Maricela grip the handle of the

pail easier, her father wrapped a long strip of old

bicycle inner tube very tightly around the handle. But

when Maricela's hand sweated, the smooth rubber got

slippery. So her father wound a thin rope around the

rubber. This way, Maricela could hold it better. |

|

007

|

|

|

As time passed she learned how to carry a

bucket of clothes on her head-then a bucket of water. To

do this took a lot of practice with balance and control of

movement. She just had to keep her legs farther apart to

keep her balance. Her mother was almost afraid to let

her try carrying the water. But Maricela was stubborn- and

she did it! Maricela also discovered that if she floated a

gourd dipper (or a big leaf) on top of the water, it

helped keep the water from splashing out. |

|

So, by trying different things, Maricela's

family, and Maricela herself, learned ways to create

therapy and aids that were effective, useful, and

enjoyable.

Maricela did learn to walk better, and to

use her hands and arms to do many things. But this took a

long time. Sometimes she would try something that was too

hard, and almost give up. But when her little brother

would say she could not do it, she would keep trying until

she succeeded.

Even when Maricela liked doing something,

because she was a child she would get bored and not keep

doing it for long. Her parents always had to look for new

ways for her to get her therapy. It became a challenge and

a game for them, too. |

|

|

Of course, Maricela loved horses. So her

father made her a rocking horse out of old logs, branches

of trees, and a piece of rope for a tail. |

|

|

Her father noticed that she was beginning

to walk on tiptoe, so he made special stirrups for the

rocking horse. With these, when she rocked, her feet

stretched up in a more normal position. |

|

The rocking horse kept her knees apart,

strengthened her hands, and helped her improve her

balance. Maricela loved her horse and sometimes rocked for

an hour or more. When she got off, it seemed she could

walk better.

After Maricela had learned to ride the

rocking horse, she wanted to ride the real thing. She

begged and begged. So one day her father let her ride with

him to the cornfield on his donkey. He suggested she ride

in front of him where he could hold her. But she insisted

on riding behind, like other children do. |

|

|

So he fixed some stirrups and let her

ride behind. Her legs were spread wide and she hung on

tightly. It was excellent therapy - but nobody called it

that. |

|

|

In the cornfield she helped her father

and brother clean the weeds out from among the young corn

plants. That was good for the young plants-and for her,

too! But after several trips to the cornfield on the

donkey with her father, Maricela begged him to let her

ride alone. He was nervous, but he let her try. |

|

She could do it-and what confidence it

gave her! Soon Maricela was preparing lunch for her father

and brother and taking it to them in the cornfield-all by

herself. Now she found she could do many other things she

never thought she could. Although she was still awkward,

and at times had to look for special ways to do things,

she found she could do most anything she wanted or needed

to. |

|

008 |

| The example of Maricela's

'therapy' cannot and should not be copied-but instead,

learned from. In fact, the story suggests that no

approach to rehabilitation should be copied exactly.

Our challenge is to understand each child's needs, and

then to look for ways to adapt her rehabilitation

to both the limitations and possibilities within her

family and community. We must always look for

ways to make therapy functional and fun. Recently, some

'appropriate technology' groups have tried to adapt

standard 'rehabilitation aids' to poor rural communities.

However, many of their designs are modeled fairly closely

after the same old city originals, using bamboo and string

instead of plastic and aluminum. Some of these low-cost

designs are excellent. But more effort is needed to make

use of the unique possibilities for rehabilitation and

therapy that exist in the village, farm, or fishing camp.

Maricela's family did just this. The basket of corn,

the washing rock, the rocking horse, and the donkey all

became 'therapy aids' to help Maricela spread her spastic

legs, and at the same time, to take part in the life of

her family and community.

But not every family shells corn in baskets, washes

clothes on rocks, or has a donkey. And not every disabled

child has Maricela's needs and strengths. So we repeat:

| We should encourage each

family to observe the specific needs and

possibilities of their disabled child, to understand

the basic principles of the therapy needed, and then

to look for ways to adapt the therapy to the child's

and family's daily life. |

|

|

|