| 183

|

CHAPTER 30

Evolution

of the Whirlwind Wheelchair Evolution

of the Whirlwind Wheelchair

The Best wheelchair Designers? Wheelchair Riders!

Everest and Jennings is the brand name of the world's largest

wheelchair manufacturer. Many people do not realize that the original

designer and founder of this global wheelchair business was disabled and

rode a wheelchair himself. The original "E&J" wheelchair - which

was a breakthrough in its day - grew out of a disabled person's creative

response to an unmet personal need.

But as E&J Industries grew, the company became more interested in

mass-production than in innovation. Fortunately, however, other disabled

persons have continued to advance the state of the art. Like

Herbert Everest, many of the most innovative wheelchair designers in the

past 20 years have themselves been wheelchair riders. |

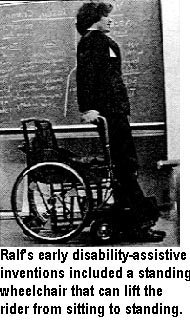

RALF HOTCHKISS AND THE WHIRLWIND

One of the world's most caring and creative wheelchair designers and

builders is Ralf Hotchkiss, who lives in California, USA. Ralf became

paraplegic (paralyzed from his chest down) from a motorcycle crash when he

was a teenager. Since then, Ralf trained as a mechanical engineer, and has

designed and built a wide range of innovative wheelchairs and other

equipment.

When Ralf first decided to build a 4-wheel drive wheelchair,

he had a hard time figuring a way to transfer power from the large back

wheels to the small front wheels. The obvious solution was to use bicycle

chains. But for this, the front wheels would need to not swivel (pivot) to

make turns, as do caster wheels of most wheelchairs.

Furthermore, caster wheels need to be fairly small to avoid bumping the

footrests when they pivot. But, to move easily on rough ground, Ralf's

front wheels needed to be relatively large. What to do???

The solution, Ralf explains, came from the Bible: the so-called

Ezekiel Wheel, a circle of small wheels that together form a larger wheel.

With this idea, Ralf created a front wheel made of a series of small

rubber cones, positioned in a circle around the central hub. Each cone is

mounted on its own ball bearings, so it can roll sideways, while the wheel

as a whole rolls forward. This combination of several small wheels within

a bigger one gives a multi-directional roll similar to that of a caster

wheel. However, the forward direction of the main wheel is fixed and it

does not pivot. This is what Ralf needed for his 4-wheel drive. |

| 184

|

Low-Cost, High-Quality Wheelchairs Made by Third World Riders

Although Ralf's 4-wheel drive wheelchair worked well, it never became

popular. Building it was too costly and time consuming. Just the front

wheels used 24 bearings and 20 individually vulcanized cones.

Ralf's interest turned to developing low-cost wheelchairs for the Third

World, using "appropriate technology." His incentive was sparked on a

visit to Nicaragua in 1980, shortly after the Sandinistas overthrew the

Somoza dictatorship. A group of young Sandinistas who had been spinal-cord

injured during the war had formed a grassroots group called

Organization of Disabled Revolutionaries (ORD). They had so much

trouble getting wheelchairs that four of their members were sharing a

single wheelchair. Most wheelchairs in Nicaragua were imported from the

USA. With the stiffening US embargo, both chairs and spare parts were very

hard to find. The ORD members had difficulty reintegrating into society

and finding work because they lacked mobility. Some, whose wheelchairs had

broken down, had gone back to dragging themselves about in their homes,

unable to leave.

For these reasons, the Disabled Revolutionaries set up a small

wheelchair repair shop. But they ran into problems. Commercial imported

chairs, such as E&Js, have poor-quality bearings which wear out

quickly in a rough, dusty environment. Because they are not a standard

size, they could only be replaced with over-priced bearings purchased from

the original manufacturer. The cost was prohibitive. In places like

Nicaragua, where bearings of any kind are often not available, wheelchair

maintenance becomes extremely difficult.

Clearly, such dependence on expensive, hard-to-maintain, imported

chairs increased people's handicaps. Ralf worked with ORD to design a

low-cost wheelchair that could be built from local materials by

modestly-skilled disabled workers. The result was the Torbellino,

or Whirlwind Wheelchair. Within a year, ORD was operating a mini-factory

in which a team of disabled persons built this home-grown design.

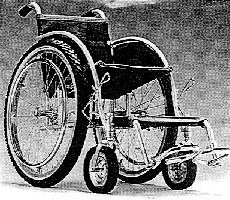

THE WHIRLWIND WHEELCHAIR is relatively easy

to build in a modestly-equipped shop. Yet its quality is excellent. As a

wheelchair rider himself, Ralf appreciates the need for a light-weight,

compact, easy-rolling, trouble-free chair. The design of the Whirlwind is

simple and stream-lined, but a great deal of skillful engineering has gone

into it.

The frame of the chair is made from electric-conduit steel tubing,

available in building supply stores around the world. The back wheels are

bicycle wheels. The bearings (of the early model) are standard high-speed

bearings used in small electric machinery. Used bearings can often be

obtained at very low cost in electrical repair shops. These are finely

made bearings for high speed use. Even secondhand ones, used in a

wheelchair, will long outlast commercial wheelchair bearings.

The beauty of the Whirlwind is that it is made in small

community shops by disabled people who recognize the need for a chair that

is adapted to the needs of the individual rider.

These wheelchairs tend to be custom-built or adapted. In the process, new

design opportunities arise, and the chairs come closer to matching the

varied needs of their users. |

| 185

|

The long-term vision:

WHEELCHAIRS FOR ALL WHO NEED THEM

Since helping ORD in Nicaragua, Ralf has traveled around the world,

facilitating workshops and helping groups of disabled persons begin to

produce appropriate wheelchairs. One of the first groups he worked with

was PROJIMO, in the mountains of Western Mexico. Over the years, Ralf has

led workshops and worked with disabled wheelchair builders in 30 countries

in Latin America, Africa, Asia, and Russia.

Ralf calculates that, of the 20 million people in the Third

World today who need wheelchairs, fewer than one percent have them.

He dreams of the day when all who need a wheelchair will have a chair

fully suited to their needs. To this end, he and his friend, Peter

Pfaelzer at San Francisco State University, formed Wheeled

Mobility, a small non-profit organization which is rapidly

turning into an international network of wheelchair builders and

designers. If there are ever to be enough wheelchairs - chairs

that are truly liberating to their riders - production must be

decentralized and the building process must be demystified, with users

leading the process.

RECENT WHIRLWIND INNOVATIONS

The basic design of the Whirlwind keeps evolving. Not

only has Ralf continued to design and test new features himself, but he

has gathered new ideas from groups of disabled persons around the world

who are building local variations of the Whirlwind.

It should be noted that many of these new features were developed in

collaboration with disabled persons who expressed difficulties with the

existing design or who wanted some particular modification.

In this book, we do not give detailed instructions for making the

Whirlwind wheelchair. A brief description can be found in the book,

Disabled Village Children. Very detailed instructions - including

suggestions for setting up and stocking a shop - are in Ralf's fine

handbook, Independence Through Mobility (see

page 343).

For years, Ralf has been revising and updating this book, but new ideas

come so fast that it is a never-ending process. In this chapter we

will give a preview of just a few of the most innovative modifications and

improvements of the Whirlwind chair. While developed primarily

for the Whirlwind, most of these innovations can be adapted to other

models, or even to commercial wheelchairs.

1. Front Wheels and Tires

The front caster wheels and tires of the Whirlwind have presented some

big design challenges. Caster wheels are complex and costly. They require

two sets of bearings, one vertical and one horizontal, so that the wheels

can swivel, as well as rotate. (The swivel is what allows the chair to

make turns.)

The basic front-caster design and the wheel forks remain much the same

as in Ralf's original book (and in Disabled Village Children). A

new design for bearings is discussed under entry #2. Here, we look at

innovations in wheels and tires.

|

| 186

|

FRONT WHEELS AND TIRES TO SUIT DIFFICULT TERRAIN:

A THORNY PROBLEM

Most modern commercial wheelchairs now come with tiny, hard, rubber

or plastic front wheels. These are good for gliding over hospital floors

or smooth, paved streets. But they function poorly on the rough, sandy

paths of villages, or on the pitted, irregular roads of many Third World

cities. For difficult or sandy terrain, front wheels need to be

relatively big (6 to 9 inches in diameter) and wide (1+1/2 inches or

more).

Pneumatic tires (filled with air, under pressure)

are light-weight, and on rough terrain they give a much smoother ride

(which may add to the life of the wheelchair - and the rider).

But air-filled tires also have short-comings. On rocky or thorny

paths they puncture easily and often need to be patched and pumped up.

Also, pneumatic tires that fit small caster wheels tend to be

outrageously expensive. And, in many countries, they are simply not

available. In the original version of Independence Through Mobility,

Ralf gave an address in China where pneumatic tires and tubes can be

bought in large quantities at relatively low cost. But this is hardly an

ideal solution for equipment designed to use local, easily obtained

materials.

The wheels have presented another problem. In the

early Whirlwind design, Ralf recommended making front wheels from two

discs of hard wood, glued together, with their grain crossing (at right

angles) to prevent splitting. The photos of the Whirlwind, below and on

p.195, show the wooden wheels.

These wooden wheels were tried at PROJIMO in Mexico, but many users

found them unsatisfactory. In spite of attempts to waterproof them with

heavy varnish or epoxy finish, in the mud and rain they soon rotted and

cracked. Riders in other countries reported similar problems. Another

problem was that some people who wanted to purchase a wheelchair thought

wooden wheels were primitive and ugly. They insisted on having "modern"

wheels, even if more costly. Whatever the reasons, such preferences must

be taken into account.

Molded aluminum wheels were another alternative

considered by Ralf.

Workshops in Brazil and Bangladesh cast and lathe-turn their own

aluminum wheels. But for most small production centers, this is

impractical. The set-up costs are prohibitive. |

| 187

|

|

A rubber T tire, clamped between metal plates. A

new design came from RESCU, a production center in Zimbabwe where

disabled workers build assistive equipment, including the Whirlwind

wheelchair. The front wheels consist of two round sheet-metal

plates which grip a molded rubber tire.

The tire, in cross section, is T-shaped. The center-arm of the T

projects inward, and is firmly held with bolts between the 2 metal

plates. The tire is vulcanized (heat-molded) in a specially

lathe-turned steel mold. Once the mold is made, any shop that retreads

car tires can produce these T-tires in small or large quantities at a

relatively low cost.

The wheel is made by cutting two round disks of sheet metal. The

disks must be widely separated at the center to hold the hub firmly,

and shaped so they can grip the T-tire. A dye of lathe-turned steel is

needed to hammer, press or spin the disks into shape.

The advantage of this Zimbabwe wheel is that, after a (fairly

costly) initial investment for the molds and dyes, the production cost

can be quite low. The tire, made of the same rubber as a car tire, is

nearly indestructible. Its broad, T-shaped base has almost the same

flexibility and springiness as a pneumatic tire. But it never

punctures. Wider tires can be made for sand, to prevent sinking in.

Problem: In Zimbabwe, the wheel was made

of fairly thick sheet metal, pressed into shape in a large metal-press

delivering tons of weight. In redesigning the wheel for smaller shops

without such massive presses, Ralf began to experiment with a thinner

grade of sheet-metal that could be hammered into shape when the metal

disk was clamped over a dye. The PROJIMO wheel-chair builders tried

making these wheels. At first, they appeared to work well. But, after

repeated bumps into rocks and curbs, the metal disks bent and finally

collapsed. The PROJIMO team tried using thicker sheet-metal, but it

was too difficult to hammer into shape. Groups experimenting in other

countries ran into similar problems.

Solution: An all-rubber wheel and tire.

After exploring many possibilities, Ralf found a simple solution.

Do away with the sheet-metal disks and mold the entire tire

and wheel out of vulcanized rubber, as a single unit.

The central part of the wheel is cast thick enough to make it

inflexible. The wide outer-edge that rolls against the ground is thin

enough to provide a spongy flexibility.

The wide center-part of the wheel is molded to grip the hub. A

flange, welded to the hub, is bolted to the wheel.

A big advantage to this all-rubber wheel is that it bends easily,

to ride smoothly over irregular terrain. These simplified wheels show

great promise. Eventually, they may be used for both front and rear

wheels ofall-terrain wheelchairs. |

| 188

|

2. Bearings

Among the biggest problems with many wheelchairs are the bearings.

Commercial chairs use off-size ball bearings of relatively poor

quality. They soon wear out, making the wheels wobbly and hard to

push. Since the bearings are not a common size, often they cannot be

replaced locally, but must be obtained at high cost from the

wheelchair supplier or the manufacturer. Where chairs are imported,

this may be very difficult or impossible. The Third World is littered

with carcasses of fancy imported chairs whose bearings wore out.

For this reason, the original Whirlwind design

uses local, widely available bearings. If dust or dirt get into

the bearings, it can ruin them. So, sealed bearings are

recommended. Though more costly, the user saves money in the long

run.

Second-hand high-speed, sealed bearings of a workable

size (5/8 inch inside diameter, 1+3/8 inch outside diameter - or

15 x 35 mm metric equivalent) can often be found in junk yards (in

starter motors of old cars) or in small motor or power tool repair

shops. (For more details, see Independence Through Mobility.)

Problem: When PROJIMO began making wheelchairs, it

could get all the second-hand bearings it needed free or at low

cost from friendly repair shop owners in the closest cities. But

as the program produced more and more chairs, the repair shops ran

out of second-hand bearings. PROJIMO had to buy new bearings,

which were very expensive. The 12 sets of bearings needed for a

wheelchair cost as much as all the remaining materials! This

pushed up the price so much that many poor families could not

afford it. Many other wheelchair-making shops have had a similar

experience. |

|

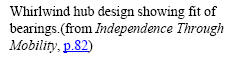

Solution: An idea to solve this problem

came from India. On a visit there, Ralf Hotchkiss inspected the huge

wheels of the traditional ox carts. They used an ancient form of

rod bearing, or "needle bearings." The wheels rolled

on a series of metal rods which fit snugly between the iron hub and

the axle.

Ralf experimented with hubs that, instead of ball bearings, use

metal rods that roll between the axle and the hub tube. But the rods

sometimes jammed in the hub.

An

old mountain farmer in the eastern USA solved this problem by showing

Ralf that thinner rods in a longer hub do not jam. Ralf now uses

carpenter's nails with their heads cut off. The nails form a circle of

rollers between the axle bolt and metal hub tube. An

old mountain farmer in the eastern USA solved this problem by showing

Ralf that thinner rods in a longer hub do not jam. Ralf now uses

carpenter's nails with their heads cut off. The nails form a circle of

rollers between the axle bolt and metal hub tube.

Ralf has tested the ease with which the wheels turn compared to

ball bearings, and finds them equal. The cost of materials for rod

bearings is a fraction of that of commercial ball bearings. Rod

bearings require more work, but durability tests indicate that they

last many times longer. (Whereas ball bearings bear the weight of

chair and rider on a tiny point on each tiny ball, with rods, the

weight - and wear - is spread over the full length of the rods.)

These new (though ancient) bearings show great promise. Hopefully

they will contribute toward providing high-quality, long-lasting

wheelchairs to many of the millions of people who need them, at a cost

more within their reach. |

| 189

|

3. Folding Mechanism, with Adjustable Chair Width

Different adjustments on wheelchairs. People who

ride wheelchairs come in all shapes and sizes. So should wheelchairs.

Many commercial chairs - although the basic models are standardized -

come with adjustable footrests, armrests, and alternative positions

for the rear hubs.

Hub position. By changing the up-and-down position

of the hubs in relation to the chair, the height and tilt of the seat

can be changed. By changing the front-to-back position of the hubs,

the balance of the chair can be changed. For example, a person without

legs may need the rear hubs mounted farther back to avoid falling over

backwards when going up-hill.

An advantage to producing wheelchairs in small,

community-based shops is that often they can be custom-made.

Rather than adding a lot of mechanisms for adjustments to meet

different user's needs (which add to both weight and cost), each chair

can be personalized from the start, to meet the specific needs of the

intended user. If the wheelchair makers are also wheelchair riders,

they are likely to be more aware of and responsive to those needs, and

to include the user in the planning and design process.

Nevertheless, even in a small community shop, some amount of

standardization can make production quicker, easier, and cheaper. It

helps to have a selection of ready-made chairs available when they are

needed. That way the person can try different chairs and pick the one

that comes closest to meeting her or his needs. Last minute

adjustments (or even more substantial changes) can then be made

according to the individual's requirements.

Goodness of fit - in terms of size, width, seat angle, angle and

height of back, need for armrests, position of footrests, etc. - is

essential. Decisions need to be made with the user, not

for her, allowing enough time to test different alternatives and

make well-informed decisions.

ADJUSTABLE FEATURES OF THE WHIRLWIND.

Although the Whirlwind has a basic (if evolving) design, it can be

built and modified in different ways for different users. The

height of the footrests can be easily adjusted by the user.

Also, in response to his own need and that of others with spastic

ankles, a PROJIMO wheelchair builder, Martín Pérez (see Chapters

37 and 39),

has designed a simple way to adjust the sideways angle of the

footrests.

One of the greatest needs for adjustability in wheelchairs is the

width of the seat, and thereby the width of

the whole chair. Correct width is important for the stability

and comfort of the rider, and for her ease in pushing the chair. A new

design for easy adjustment of chair width has been developed, together

with a new mechanism for folding the chair.

|

| 190

|

| Folding is important.

For many wheelchair riders, it is essential that their chair can fold,

to fit into a narrow space. This is especially important for those who

need to travel in a bus, carry their chair in the back of a car, or

pack it on a donkey.

Problem: The original Whirlwind design

included an upright X-brace that folded like scissors, as do most

commercial chairs. But to fold well, the measurements, welds, and

alignment must be exact. In PROJIMO, as in many small shops run by

disabled persons, many workers are still learning their skills. There

are few highly skilled crafts-persons. The resulting wheelchairs were

often very difficult to fold. Users expressed their frustration.

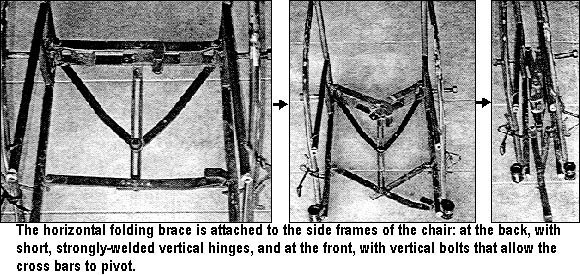

Solution:a horizontal folding device. To

solve this common problem, Ralf and friends experimented with

alternative folding devices until they came up with one that was more

fool-proof. The new design folds horizontally, rather than vertically.

Although it has more pieces and uses more welds than the X-brace, it

requires less skill and precision to build, and gives consistently

good results. PROJIMO now uses this new folding device in all its

Whirlwind chairs, and has had fewer complaints.

Narrowing the chair to get through doorways. On

experimenting with the new folding mechanism, users discovered that

they could easily narrow the width of the chair while sitting in it.

They pull the handle under the seat forward, and then pull the wheels

in, closer to their body. This offered a solution to another big

problem of wheelchair riders in many countries: getting through narrow

doorways. (See Luz's story on page 17.)

With the new design, to go through a narrow door the user simply

pulls the sides of the chair in against her hips, and rolls through.

(With an X-brace, narrowing the chair is much harder, because it folds

against gravity and the person's own weight holds it wide open.)

Adjustable chair and seat width. The horizontal

folding mechanism also lends itself to adjusting the seat width to

match the hip-width of the user. Small holes can be drilled in the

cross bars of the adjustment device, so that the chair width can be

adjusted, depending on which set of holes the center bolt is passed

through. |

| 191

|

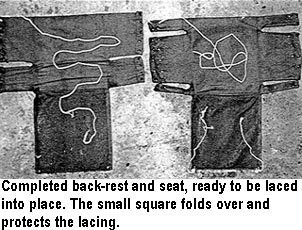

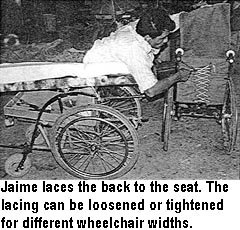

| Upholstery. To avoid

having to make new upholstery with different measurements for

different seat adjustments, Ralf has devised wrap-around seat and

back-rest cloths that can be laced up at different widths.

The patterns for the back-rest and seat are similar.

They consists of one square just a little bigger than the desired size

of the back-rest or seat, and another square, 4 times as big.

Hem the edges of both squares to prevent fraying. Then, fold the

big square in half, and cut grooves as shown here. Sew together at all

edges, except where the small square will be attached. Turn the

resulting sack inside out, and sew on the small square. Make holes for

lacing as shown.

How appropriate is the new folding mechanism and adjustable

seat?

The answer depends on who you ask. Wheelchair riders and users

(including Ralf) have mixed feelings. One of the beauties of the early

Whirlwind design (with the vertical X-frame) is its simplicity,

streamlined look, relatively few parts, and few welded joints (all of

which contributed to the chair's low weight and low cost).

The new folding mechanism with its adjustable seat width solves a

number of problems but sacrifices some of the Whirlwind's graceful

look and adds a bit of weight. Some users like being able to adjust

the chair to their own body width, and to narrow it easily to pass

through narrow doorways. Other users think it "looks funny" and prefer

the more conventional X-brace. (For some people, appearance is more

important than function.)

The PROJIMO wheelchair builders are delighted because - although

the new folding mechanism takes more welds and looks more complex -

for them, it is easier to build successfully. That is important.

Designs must be appropriate for builders as well as users.

The search for better designs continues. Ralf's team is now

experimenting with a folding mechanism developed by blacksmiths in

Nyabondo, Kenya. This uses a vertical X-brace that is easier to build

than is Ralf's original design.

There is always room for improvement.

And improvements are always possible when builders and users work

together creatively. |

|