| 221

|

CHAPTER 34

A Front-Wheel-Drive Wheelchair for Aidé:

Lessons Learned from an Experiment that Failed

AIDÉ is a 14 year old girl who is multiply

disabled as a result of brain damage at birth. Her mind works at about the

level of a 6- or 8-month-old child. She cannot speak, but she does

communicate, in a limited way, through grunts and facial expressions.

Physically, she has good head and trunk control. But she has a lot of

spasticity, especially in the lower part of her body. On her first visit

to PROJIMO, she was unable to move herself about or feed herself. She had

little sense of the potential usefulness of her hands. But she would

occasionally take hold of different objects and hold them for a moment,

then drop them.

Aidé's family is very poor. Her parents put most of their energy

into obtaining food and other resources to meet the family's basic needs.

They did not know what to do with Aidé. As a result, they did little more

than feed, bathe and clothe her.

Unmet Potential. Even at PROJIMO, no one expects that

Aidé will ever be able to do much for herself. She responded little to

early stimulation activities or play-things that were tried with her.

The team thought that if Aidé could begin to move herself about a bit

in a wheelchair, this self-created movement might increase her awareness

of her body's position and the usefulness of her arms and hands. They

provided a wheelchair. Inez held her hands on the hand-rims and rolled the

chair back and forth, hoping she would begin to make the connection

between the movement of her hands and that of the chair.

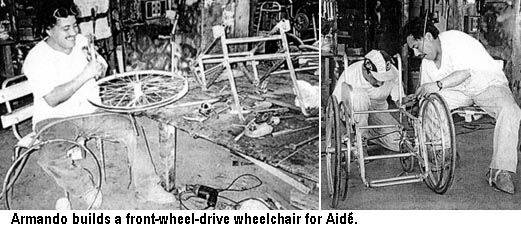

A New Wheelchair Design. Aidé tried PROJIMO's

wheelchair for a little while, and soon gave up. One difficulty was that,

with her spastic arms and shoulders, she had trouble reaching the

wheel rims. PROJIMO-made wheelchairs, like most commercial

chairs, have the large wheels at the back and the small caster wheels up

front. A visiting therapist, Ann Hallum, pointed out that many persons

with spasticity or limited range of motion find it hard to reach back far

enough to effectively push the rear wheels. So PROJIMO's wheelchair

makers, Armando and Jaime, decided to design a wheelchair with the

large wheels in the front and the small casters at the back.

Another reason why persons like Aidé have trouble moving their

wheelchairs is that the hand-rims, which are mounted on the outside of the

large wheels, are so widely separated. So, Armando decided to try

mounting the hand-rims on the inner side of the wheels. Closer to

the rider's body, they would hopefully be easier for her to reach and to

push.

A possible advantage of the inward position of the hand-rims is that

the wheels are further apart. This wide wheel-base should provide

stability and less likelihood of tipping over. The chair could be safer

for persons with strong uncontrolled movements.

Also, for a person with limited control, hand-rims on the inner side of

the wheels protect the knuckles from banging into doorways and other

objects. |

| 222

|

| The newly designed chair, with

front-wheel-drive and internal hand-rims, was built in 4 days. It

was tested, not only by Aidé, but also by Tere, Lupita, and Carlos, all of

whom have spasticity that makes it hard for them to push rear-wheel-drive

wheelchairs. Although the new chair did help to resolve some of the

difficulties that some users had, none were happy with it.

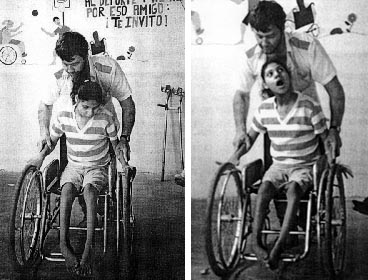

Inez worked a lot with Aidé in her new chair. He found it easier to

position her spastic hands on the wheels, now that they were mounted

further forward. She seemed more comfortable that way and, in time, began

to close her hands on the wheels.

Inez would hold her wrists and push them forward, helping Aidé to move

the chair.

However, Aidé was unable to grip the hand-rims, that were mounted to

the inside of the wheels. Her spastic fingers would bump into the wheels. |

| 223

|

SHORTCOMINGS

OF THE NEW DESIGN SHORTCOMINGS

OF THE NEW DESIGN

It is still too early to know if the new wheelchair will

benefit Aidé. So far, she still has not made much effort to push

it by herself. However, she has begun to occasionally take hold of the

large front wheels. This she had not done when the wheels were mounted

further back.

Inez continues to work with Aidé daily. He hopes that, at some point,

she will discover the joy of moving herself by pushing on the wheels.

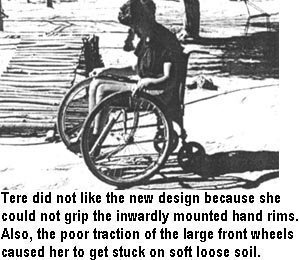

Tere, Lupita, and Carlos also tried the front-wheel-drive

wheelchair. Both Tere and Lupita could reach the front-mounted

wheels more easily. But, when they tried to grip the inward-mounted

hand-rims, like Aidé, they had trouble fitting their spastic fingers

between the rims and wheels. So Armando widened the space between wheels

and the rims.

But still the girls had trouble. The team decided that putting

the hand rims on the inner side of the wheels was simply not practical.

Neither girl found the new design acceptable.

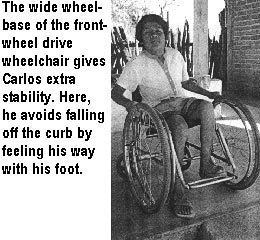

Carlos, on the other hand, did not care where the

hand-rims were. He always grips the tire, not the rim. However, the

chair's unusually wide wheel-base gave the blind boy more stability when

he tilted off a curb with one wheel, and in other spots where he might

have tipped over in a narrow chair. For Carlos, the wider

wheel-base was helpful. (To avoid accidents, Carlos also learned

to "see" with his foot. See next page.)

Poor traction was the biggest problem with the

front-mounted large wheels. On a smooth, level cement surface, Carlos,

Lupita, and Tere could move the chair about fairly easily. But, on an

upward slope, or on sandy or uneven ground, the front wheels slipped. This

happens because the rider's weight is mostly over the small, back

caster-wheels, which dig into sand and stop short on a pitted surface.

There is simply not enough weight over the large front wheels for them to

firmly grip the ground.

With the front-wheel-drive chair, the only way to get good traction on

a sloping or irregular surface is for the rider to lean far forward,

shifting her weight over the front wheels. This, of course, can be

difficult, especially for persons with spasticity. The team concluded that

front-wheel-drive wheelchairs are of limited usefulness,

particularly in rough, sandy, or uneven terrain.

Learning from our mistakes. Not all innovations are

successful. But we can learn a lot, even from efforts that fail. One

lesson is extremely important:

|

Adequate trials of new designs are

essential, and must include the intended users,

within the local environment where they live. |

|

| 224

|

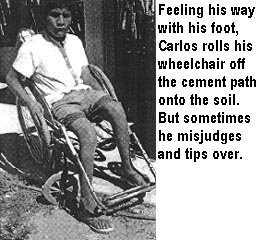

Carlos and his "Seeing-Eye Foot"

Because Carlos is almost completely blind, he sometimes has a hard time

finding his way in his wheelchair. However, he has figured out different

ways to stay on paths and to avoid bumping into things.

In Chapter 32 we saw how Carlos recruited a "seeing-eye person" to

guide him while he pushes her wheelchair.

Since Carlos needs both his hands to drive his wheelchair, he cannot

use a cane to feel his way, as many blind persons do. Instead of a

cane, he has learned to use his right foot. He takes his foot off

the foot-rest and puts it lightly on the ground in front of him. As he

rolls forward, with his foot he can feel when he begins to go off a

pathway or curb.

That way, he can often correct his direction before he has a mishap.

Although Carlos' seeing-eye foot serves him well, sometimes he forgets

to use it. Or, at times, he tries to maneuver his wheelchair over curbs or

rough terrain, and the chair tips over. He has had a few nasty falls.

For this reason, the front-wheel-drive wheelchair, with its

widely separated front wheels, is safer for Carlos than is a narrow chair.

The wide chair tips over sideways less easily. Having the large

wheels in front also appears to give more stability.

Nevertheless, on loose or sandy soil, the front-wheel-drive chair has poor

traction. Often, Carlos found himself trapped in pockets of loose soil

where the front wheels would slip, and where he could not wheel himself

out without help. As a result, Carlos prefers his narrower,

rear-wheel-drive wheelchair - even though he tips over more often. |

| 225

|

WARNING:

Don't Assume That All the Designs You See in Pamphlets or Books on

"Appropriate Technology" Are Appropriate.

Many booklets on "appropriate technology" for disabled people show

designs of wheelchairs and hand-powered tricycles with front-wheel-drive.

Such chairs are often given to disabled persons, especially in Asia and

Africa. They may work fairly well in exhibition halls, and on level

hard-surfaced roads. But on rough terrain they are likely to

further handicap the user. The rider may need an assistant to

push her in circumstances where a better designed wheelchair or tricycle

could provide more independent mobility.

| CAUTION: The various designs of front-wheel-drive

wheelchairs and tricycles shown here are taken from manuals and

instruction sheets on equipment for disabled people.

But in some circumstances, instead of increasing the

rider's freedom through mobility, these models may cause greater

dependence, need for assistance, or inability to venture forth.

However ...

for certain children, a front wheel drive wheelchair may be

the best choice (see below).

|

SOME CHILDREN WITH CEREBRAL PALSY FIND BIG FRONT WHEELS EASIER TO

REACH AND PUSH

As with most rules, there are exceptions. Front-wheel-drive chairs

are often inappropriate. But some children with spasticity, like Aidé,

may find large front wheels easier to handle. Trollies and wheeled cots

(see page 235) often work better with the

big wheels up front.

A scooter board for certain children with cerebral

palsy has been designed with the large wheels positioned right

under the child, and with small wheels both at the back

and front. For travel on rough ground, the child can learn to

balance on the center wheels and barely touch the ground with the

others.

This scooter slopes forward, so that a child with hips that thrust

him backward, or that do not bend to 90 degrees, can sit up straight.

(See positive seating, Chapter 4.) |

| 226

|

| REMEMBER: Some of the

best design improvements come from the ideas and suggestions of the

persons who try them out and will use them. This is true even

for children. The child may not always be right. But doctors,

therapists, and technicians are not always right either, especially if

they do not live in the same situation and experience the same barriers

and desires. By respecting each other's special knowledge and looking

for solutions together, we can more nearly meet the disabled person's

needs.

Note: The above front-wheel-drive chair not only risks tipping

backward, it will lose traction going uphill, The front wheels do not

support enough of the child's weight to grip well, so they will slip.

Mounting the rear caster wheel farther back will

help prevent the chair from tipping over backwards on an uphill slope.

It will also shift more weight over the front wheels and give them

better traction. For these reasons, this modified design is included in

the book, Disabled Village Children. But even when the rear

caster is farther back, traction is not good.

Another problem with front-wheel-drive wheelchairs is that

the rider can not do "wheelies."

POPPING A WHEELIE TO MOVE OVER ROUGH TERRAIN

A rule to consider:

Never follow instructions blindly. Use common sense and

creativity.

|

|