| 047

|

CHAPTER 4

Positive Seating to Help Toño See,

and Edgar Learn to Walk

TOÑO was 4 years old when his concerned parents

brought him to PROJIMO from a neighboring village. His brain had been

damaged shortly after he was born, apparently by meningitis. He was multiply

disabled and very small for his age.

In the first meeting with Mari and other members of the village

rehabilitation team, Toño's worried father explained, "I'm not even sure he

can see. We try to sit him up so he can look at things around him. But he

just droops his head and stares at his lap. He doesn't show interest in

anything.

Observation and examination. Watching Toño, the team

observed that his overall development was quite delayed. He responded very

little to people and things around him. He did not reach for or play with

toys.

Mari tested Toño's vision by moving a small light in front of his eyes.

Occasionally, his eyes followed the light, but sometimes they did not. "I

think he sees," said Toño's mother. "He's just not used to looking at

things."

Toño could sit by himself, but his whole body was floppy and he had

little head control. The team tried sitting him in a special seat that was

his size. An H-shaped strap held his body upright. But even then, his head

drooped far forward. To keep his head from falling forward, they had to tilt

the seat so far back that his head faced upward rather than outward. Only

when he cried did his drooping head come up for a moment.

"That gives me an idea," said Mari. "Let's try positive seating.

It might help him sit more upright." She explained that positive seating

means that the seat tilts forward (see Chapter 1,

page 35). This differs from negative seating, the common

position where the seat slants slightly back.

Experimentation. Mari asked Toño's father to sit the boy

in a simple child's chair. He drooped over at once. Then Mari asked his

father to put a book under the back of the special seat in which Toño sat,

to tilt it a bit forward. The boy's head still drooped. But, when another

book tilted the seat farther forward, an amazing thing happened. Toño's body

gradually straightened and he lifted his head.

When Toño's father walked across the room in front of his son, the boy

turned his head, following with his eyes. "He sees me!" exclaimed his father

in delight. "That's the first time he has ever watched anybody move in front

of him! My boy can see!" |

| 048

|

Why Positive (Forward Tilting) Seating Helps Some Children

Positive seating (sloping the seat forward) does not help all, or even

most, children with cerebral palsy or developmental delay. But it does

help some children with stiff, backward-tilting hips, or those with low

muscle tone who have trouble sitting upright. It is especially useful for

children who can sit briefly without support, but who tend to droop

forward with sagging head. Often it helps them to sit straighter and raise

their head.

The concept of positive seating is still new to many rehabilitation

workers and therapists. It is often helpful for children who, for 2

different reasons, have difficulty sitting upright. |

NOTE: Some therapists dislike the term "positive seating." This

is because both positive (forward sloping) and negative (backward

sloping) seating can be either helpful or harmful, depending on the

particular needs of each child. |

| 1. As mentioned in

Chapter 1, some children with spastic

cerebral palsy have stiffness of the hips (pelvis)

that prevents them from sitting with their back at right angles to

their thighs. When they sit on a level (horizontal) seat, they tend to

fall over backwards. Or they sit slouched with their back in a

C-shaped curve.

When the child sits on a forward-tilting seat, or

wedge, this allows her back to rise straight up from the hips. (The

pelvis is rotated to an upright position.) On this forward-slanting

seat, the child is more stable, less tense (which reduces spasticity),

and often has better head, body, and hand control.

|

|

| 2. Some children have

low muscle tone, as in the floppy (flaccid) type of

cerebral palsy, and in some mixed types. On a level seat, they tend to

slump forward and have difficulty raising their heads.

For such children, a forward-tilting seat

(positive seating) often does wonders. The forward slant causes the

child to push with her legs to keep from sliding forward. This use of

the leg muscles increases overall muscle tone, which (in some cases)

allows the child to lift her head and hold a more upright posture.

|

|

CAUTION: Each child is different. Results

with positive seating vary from excellent to counterproductive. Be sure

that - if muscle tone is increased - it gives the child greater control,

rather than triggering a stiff, spastic reaction (as it does in some

children).

Ways that Positive Seating can Speed the

Development of Certain Children

| It helps a child with back-tilted hips to sit upright. This

increases stability and relaxes spasticity so that the child is

more able to use her hands and do things. |

| It can help the floppy child to sit upright, increasing body

and head control. |

| By enabling the child to lift her head, it enables her to

watch the world around her. This stimulates vision and involves

her in family activities. It can speed her physical, mental, and

social development. |

| By encouraging use of the leg muscles, it helps prepare the

child to walk. |

|

POSITIVE SEATING AS PREPARATION FOR WALKING

Positive seating sometimes stimulates a child to use her leg muscles

(to avoid slipping off the sloping seat). This helps to strengthen the

thigh muscles that straighten the legs. Use of these muscles is essential

for standing and walking. Thus positive seating helps some children

prepare for walking at a later time. This was the case with Edgar. |

| 049

|

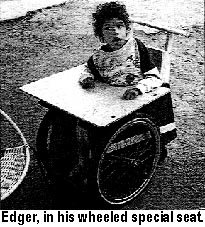

| EDGAR was 7 years old

when his mother and older brother brought him to PROJIMO from a distant

village. Like Toño, Edgar is developmentally delayed and has a type of

cerebral palsy which is primarily floppy (flaccid), with poor balance.

Also like Toño, Edgar would sit with his head drooping forward, totally

uninvolved with the world around him. He spent a lot of time staring down

at his upturned hand. His mother had tried hard to interest him in toys

and other things, but he made no effort to take hold of them. The only

thing he did with his hands was to sometimes pick at his clothing, or pull

his hair. His mother was discouraged.

The PROJIMO team carefully evaluated Edgar's needs. They helped his

mother and brother do playful activities with him, and gradually Edgar

began to take more interest in things. They designed a special seat for

him with a table and a removable frame from which were hung brightly

colored toys, bells, and rattles. These encouraged him to lift his head,

look at them, and begin to touch and handle them. (The design for this

seat is shown on page 32.)

But with all these stimulating objects and activities, Edgar showed

only a little improvement. He still spent most of his time with his head

hanging forward. When he did lift his head, it seemed to be with great

effort, and in a moment his head would droop again.

A try with positive seating. It was around this time

that the team learned about positive (forward-tilted) seating, and decided

to try it with Edgar. They repeated the experiment they had used with

Toño, but this time they sat the child on a box instead of a chair.

With the box tilted forward, Edgar sat up straighter. He also seemed

more alert. He looked at things around him like someone who had just

awakened from a dream.

After only about a minute, however, Edgar looked tired, and he slowly

began to droop again. Although at first he seemed to enjoy sitting on the

sloping box, now he began to fret. When his mother removed the brick from

under the back edge of the box, Edgar looked relieved. But he continued to

droop like a wilted flower.

After a few minutes, the team tilted the box forward again. As before,

Edgar straightened up and became more alert. But in a moment he again grew

tired and slumped over. Mari explained to Edgar's mother that, to sit

upright, Edgar had to use muscles he seldom used in his thighs, back, and

neck. So he tired quickly. For Edgar it would take time to gain the

strength he needed to stay upright for long. He would need a schedule,

with short periods of forward-tilted seating alternating with rest periods

with the seat tilted back. As the boy's strength increased, the length of

time he could sit upright on a forward-tilted seat would also increase. In

time he might learn to sit upright, even on a non-sloping seat.

|

| 050

|

DESIGNING EDGAR A WHEELCHAIR WITH ADJUSTABLE SEAT TILT

The team realized that getting Edgar used to sitting upright in a

forward-tilted seat would require frequently shifting him back and forth,

from a seat that tilted forward to one that was level (or that tilted

somewhat backward).

However, Edgar's mother worked all day in a small restaurant. Sometimes

she took Edgar with her. More often she left him at home alone for most of

the day. The child was getting too heavy to carry long distances.

It would be too much to expect Edgar's mother to carry him to the

restaurant and then to spend all day moving him in and out of a seat with

a forward slant. Things needed to be made as easy as possible for his busy

mother.

So the team decided to try to design a combination of wheelchair

and special seat, so that Edgar's mother could push him to and from

the restaurant. The wheeled seat needed to be easily adjustable, so his

mother could quickly change the tilt of the seat-board from a forward to a

backward tilt . . . if possible with the child still sitting in it.

| To change the seat-tilt, pull upward on the cord. |

| In order to change the tilt of the seat, a hinged square of plywood

fits on top of the fixed seat-board. |

| To hinge the front edge of the top seat-board, a long bolt passes

through the top board into the slot in the bottom board. |

| The back-rest of the seat is made of 2 layers of thin plywood,

separated by about 2 cm. |

| To secure the seat at the angle you have chosen, slip the rope

through the small slit in the rear board of the seat back. Knots in the

rope are tied at distances to provide 3 or 4 different seating angles.

The hook slides up and down through a long thin notch in the forward

board of the seat back. |

| A cord passing between the layers of the seat back is attached to a

metal hook in the back of the seat board. |

|

| 051

|

|

| A removable table - with a half-circle cut out to

loosely fit the child's body - provides a space for play and eating. By

holding up the child's arms, it can also help a flaccid child to sit

upright. |

| A bar for pushing the chair is mounted behind the

seat back. This position prevents the child from bumping his head, and

makes it easier to tilt back the chair to go up a curb. |

| A board in front of the feet helps prevent his feet from slipping

when the seat is sloping forward. |

| Big bicycle wheels are mounted in front (with the

small casters behind). This makes it easier for children who, because of

spasticity or for other reasons, find it hard to reach the wheels when

they are mounted farther back (see page 225). |

| When the table is not in use, it can be hung on pegs on the

push-stand. |

Designing this chair, the team observed that changing the slope of the

seat changed the height of the child relative to the table. Therefore the

table height had to be adjustable. They created a simple design that

allows adjustment of both the table height and angle.

Adjustment of the table height and angle is done by adjusting the

armrests which support the table.

Each armrest slides within a wood panel attached to the sides of the

chair by small blocks.

The many adjustable features of this chair allow the family and child

to experiment with different combinations of adjustments, to find out what

works best for the individual child. |

| 052

|

OUTCOME WITH EDGAR - AND HIS FURTHER PROGRESS

As with many children, in evaluating Edgar's progress it is difficult

to separate the benefits brought by the physical equipment from the human

support and increased stimulation that accompanied it. Certainly all the

attention, movement, handling, talking to him, and encouragement that

Edgar received during his days at PROJIMO contributed to his sense of

self-worth and readiness to hold his head higher.

Equally important was the renewed interest on the part of Edgar's

mother and the enthusiasm of his 12 year older brother, Adolfo. Adolfo

helped the PROJIMO carpenter, Mario, to build Edgar's wheelchair. Through

this involvement, Adolfo became even more eager to try it out with his

younger brother, and to help him to use it effectively. In the course of a

few days at PROJIMO, Adolfo learned a lot of skills for working with the

boy. With words, objects, and stimulating noises, he would encourage his

little brother to raise his head and look around, adding to the effect of

the tilted seat. Also important were Edgar's rides all around the village.

Back in their own village, now that Edgar had wheels, both his mother and

brother were much more inclined to take him out and include him in their

activities. His new seat seemed most effective in getting Edgar to raise

his head when he was bumping over rough terrain, and when the scenery was

constantly changing.

Edgar and his family continued to visit PROJIMO periodically for

several years. Members of the team also visited his distant village

whenever they had an opportunity. Edgar showed slow but steady progress,

physically, mentally and socially. Much of his improvement was related to

his growing ability to hold himself upright. At first, when sitting in a

forward-tilted position, he would stay erect only for a minute or two

before slumping over again. But with practice, he sat upright longer.

Eventually, he began to spend more time sitting up and looking around him,

even when he was not in his forward-tilting seat.

Preparation for walking. The forward-tilted seat also

stimulated Edgar to use his leg muscles. The boy gradually became more

able to stand and even to take a few steps with assistance. To help him

get used to bearing his weight, they made a standing frame for him.

The standing board held Edgar's legs and hips in a straighter position

than he was accustomed to. Initially they had been very stiff, with

beginnings of contractures (inability to straighten completely).

As with the positive seating, at first Edgar was put in the standing

frame for very brief periods (2 or 3 minutes). As he got used to it, the

time was lengthened. Edgar's mother and Adolfo also learned to do "range

of motion" exercises to help the child straighten out and make his stiff

joints more limber.

Edgar showed overall improvement for about two years.

Then, sadly - after the death of his father - he had a severe

setback involving self-abuse. This is discussed in

Chapter 8. |

| 053

|

Two Very Different Walkers for Edgar

For Edgar, standing with his standing frame made it

easier to hold up his head. This probably helped for the same reasons as

did tilting his seat forward. The voluntary use of his leg muscles

triggered an increase in muscle tone throughout his body.

After Edgar had used the standing frame for a few months, the team

thought he might be ready to try a walker. PROJIMO'S carpenter, Mario,

experimented with different styles and heights. Then he built a simple

wooden walker for Edgar. Adolfo and a couple of the

village children helped Mario.

Here, a school girl who assists in making simple equipment at PROJIMO

helped Edgar learn to walk. As you see, Edgar (for short but increasing

amounts of time) was able to hold up his head.

This walker's wooden wheels allow it to roll forward without having to

lift it (which Edgar could not do because of weakness and poor balance).

Also, the wheels' large size (compared to many walkers) works well on

uneven ground.

The walker has automatic brakes similar in effect to

those of some very costly commercial walkers. The braking action was

discovered by accident. The wooden wheels turn loosely on a bolt between 2

wooden struts. When the child pushes the walker forward between steps, the

wheels roll easily. But when the child puts his weight on the walker to

take steps, the wheels press against the side struts, acting as a brake.

This braking effect makes walking easier for the unsteady child with poor

balance.

Although the walker worked when someone helped Edgar hold onto it, for

a long time he made little effort to hold or walk with it by himself. What

Edgar seemed to enjoy most was hanging onto the back of Adolfo's shirt and

walking behind him. Fortunately, Adolfo enjoyed this too. So his

big brother became Edgar's custom-made "human walker."

Rehabilitation equipment can be important. But for child

development,

the warmth, stimulation, and adventures with persons the child

feels close to are essential.

|

| 054

|

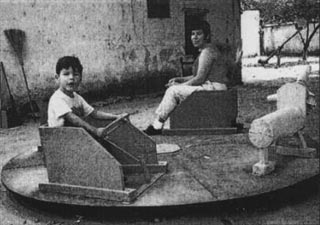

Merry-Go-Round as Therapy for Tinín

Positive seating does not work for all children with floppy

cerebral palsy. Tinín is a child for whom other approaches worked

better. When his mother brought him to PROJIMO at age 5, he had great

difficulty sitting upright, as can be seen in these photos.

The PROJIMO team experimented with positive (forward-tilting)

seating, but Tinín slumped forward so far that he would fall off the

seat, unless held. In Tinín's case, negative seating (with the seat

sloping backwards) seemed to help more than positive seating.

While the team tried everything they could think of to help Tinín sit

upright, his mother had the idea of putting him in the merry-go-round in

PROJIMO's "Playground for All Children." Actually, the idea was Tinín's.

Of the 10 or so words he spoke, one was "car." Since he first saw the

merry-go-round, which has a small car on it with a pretend steering

wheel, he kept pointing to it, saying "Car!" Clearly he wanted to sit in

it. So his mother followed his wishes.

|

A circular platform is mounted over the axle hub of a junked

car. The Thai model had 3 wooden animals to ride. But PROJIMO

included enclosed seating (little cars) so that more extensively

disabled children could also ride. |

|

|

| 055

|

| Sitting in the small "car" Tinín tried

hard to sit upright; but even with his excitement and desire, he was

only partly successful. Yet when his mother - sitting across from him -

started to turn the merry-go-round with her foot, Tinín began to

straighten up.

The

faster the merry-go-round went, the more Tinín straightened up. He hung

onto the steering wheel for dear life. Therapy was never more fun! The

faster the merry-go-round went, the more Tinín straightened up. He hung

onto the steering wheel for dear life. Therapy was never more fun!

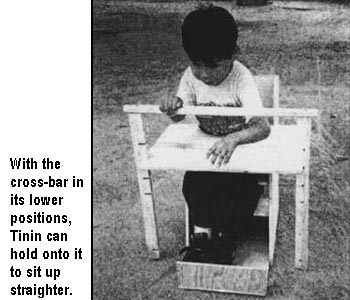

Considering how his holding onto the steering wheel seemed to help

Tinín to sit upright, the team began to experiment with special seating.

They designed a simple backward-slanting wood seat. Above its plywood

table, they added a removable cross-bar, held by upright bars with

notches that snugly grip the edge of the table. The series of notches

allows the bar to be set at different heights and slipped forwards or

backwards, to whatever positions appear best.

By following Tinín's interests and by taking an experimental

approach, his caretakers found equipment and activities that helped him

to gain more control of his body, and to sit in a way that enabled him

to learn new skills and take part more fully in life around him. |

| 056

|

The Special Seat as a Tool for Stimulation

The special seat - combined with an overhead bar with toys hanging

from it, and lots of interaction between the parents and the child - can

do a lot to help a child gain better head and hand control, and to

become more involved in the world that surrounds him.

|

|