| 325

|

Helping Fernando Walk with His Feet Pointing Forward

The following morning all 3 boys were back at PROJIMO at the crack of

dawn, eager for more. Now no one needed to coax Fernando to take part. The

big challenge to Mari and others was to find new playful ways for

Fernando's playmates to help their friend master new skills.

Fernando's manner of walking was awkward. His arms flailed with every

step, and his body pitched from side to side. His toes pointed inward more

than a pigeon's. As his knees jerked past one another it looked as if he

would surely trip himself up and fall. But he seldom did.

Despite his spasticity and strange movements, the PROJIMO team felt

that Fernando had adapted to his physical disability amazingly well. The

goal of rehabilitation should not be to make him walk normally

but to help him to function at the best of his potential.

Nevertheless, Fernando's turned-in feet did occasionally get in the way

and sometimes he came down with a crash. Years before, his father had

taken him to specialists. He had been given braces with torsion cables

to try to position his feet so they would point forward (see

page 110).

But he hated them, and he fell more often.

Now that Fernando had therapy-helpers (his young playmates) whom he

enjoyed, he was more open to learning new skills. The team thought it

might be useful to experiment with activities to teach Fernando to point

his feet forward rather than inward as he walked.

Mari had seen pictures from the Sarvodaya Community Rehabilitation

Program in Sri Lanka, where a village worker used mango leaves to

help a child learn to take more even steps. The worker placed a row of

leaves on the ground at even intervals, and asked the child to step on

these as she walked. (The method worked well when there was no wind.)

Based on this technique, the PROJIMO team devised two different methods

that might help Fernando learn to take more regular steps with his feet

pointing forward.

1. Painted footprints.

Instead

of using leaves (which can blow away or move out of place

when stepped on) the team decided to paint footsteps on the ground. The

new outdoor court for wheelchair basketball was a perfect place to paint

them. Instead

of using leaves (which can blow away or move out of place

when stepped on) the team decided to paint footsteps on the ground. The

new outdoor court for wheelchair basketball was a perfect place to paint

them.

Fernando and his playmates were eager to paint the footprints, so

Manuella and Mari invited them to do so. By now a dozen children also

wanted to help paint. But first the basketball court needed to be swept.

To make the footprints the right size and shape, Manuella made stencils

(shapes to trace around) from thick cardboard and from thin scraps of

wood. On these she traced a child's sandal and cut out a foot-shaped hole.

The children placed the stencils on the cement basketball court and

painted different bright colors in the open foot-shaped spaces. |

| 326

|

Some older boys from the village (who had come to play basketball)

helped guide the younger children in correctly spacing and positioning the

footprints. At first one boy held the wooden stencil for Fernando and

helped guide him in painting the footprints. But soon Fernando did it all

by himself. Creating the stepping aids was as much a learning experience

for the boy as was using it.

When the paint had dried, all the children wanted to walk on the

footsteps along the winding course on the basketball court. They played

follow-the-leader, each imitating the child heading the

line. Sometimes they walked fast, but more often they walked slowly,

taking care to step precisely on the footprints. They encouraged Fernando

to do the same. Fernando tried hard to place his feet correctly, and

succeeded in taking more evenly positioned, forward-pointing steps.

2. Wooden footprints.

An

alternative method was developed to help train Fernando and children with

similar gait problems. One of the girls cut more than 20 footprints from

scraps of thin boards. The children, including Fernando, painted them in

bright colors. A hole was drilled in both ends of every footprint. The

footprints were positioned on the ground in a pattern similar to the foot

paintings on the basketball court. To hold the footprints firmly, 3-inch

nails were placed through the holes in them and hammered into the earth.

Again, the children - a dozen or so including Fernando - played follow the

leader. An

alternative method was developed to help train Fernando and children with

similar gait problems. One of the girls cut more than 20 footprints from

scraps of thin boards. The children, including Fernando, painted them in

bright colors. A hole was drilled in both ends of every footprint. The

footprints were positioned on the ground in a pattern similar to the foot

paintings on the basketball court. To hold the footprints firmly, 3-inch

nails were placed through the holes in them and hammered into the earth.

Again, the children - a dozen or so including Fernando - played follow the

leader.

The wooden footprints have several advantages over the footprints

painted on cement. First, because the thickness of the wood raises them

above the ground slightly, children make a greater effort to step on them

precisely. Second, they can be easily transported. And third, they can be

adjusted according to the needs of the individual child.

|

| 327

|

|

At first, Fernando stepped on the footprints with his toes turned

in. But, with the children's encouragement, he found he could position

his feet more exactly over the footprints, thus pointing his toes in a

straighter (less pigeon-toed) position. |

Stepping between the rungs of a ladder. Another

simple method to help Fernando improve his foot control also comes

from a CBR program in Sri Lanka. As a part of the marching-on

footprints game, the team placed a long wooden ladder on the ground.

The children were asked to step in the spaces between the rungs. To do

this, Fernando had to lift his feet high and place them carefully.

Again, the children played follow-the-leader. At first Fernando

followed, but by the end began to proudly lead the other children. |

|

| 328

|

Playing Ball to Improve Coordination

To help Fernando improve hand and arm control and reduce his

spasticity, the PROJIMO team encouraged his playmates to play ball with

Fernando. They made up a game similar to volleyball, throwing a large

lightweight ball over a fishing net between two trees.

But to everyone's surprise, Fernando's closest friend, 8-year-old

Manuel, refused to play. Following his friend's example, Fernando also

refused. Mari and I begged Manuel to join the game. We explained to him

how beneficial it would be for Fernando to throw and catch the ball. But

Manuel still stubbornly refused to play. The PROJIMO workers wondered why

young Manuel, who up to now had been so eager to involve Fernando in

learning games and activities, had suddenly become so uncooperative.

Finally, we gave up on volleyball and decided to try a simpler game. We

asked the children to stand in a circle and toss the ball to the person

next to them. This time, Manuel stood up to join in. He glanced at his

friend Fernando. Then, all smiles, the two boys entered the circle.

Although much easier than volleyball, this new game was a big challenge

to Fernando. Even when the ball was thrown to him gently from a close

distance, he had a hard time catching it. At first he usually missed the

ball, his arms and hands flailing. The boy's frustration was obvious. But

soon he learned to catch the ball by pressing it against his chest with

both arms. Each time he caught the ball he grinned happily. Then he would

twist around to throw it to the child on his other side. (Twisting the

body like this often helps to reduce spasticity.) Fernando's ability to

throw the ball increased rapidly. He was delighted.

The Wisdom of a Child

Watching Fernando, the PROJIMO team gained insight into why his young

friend Manuel had so stubbornly refused to play volleyball. Manuel was

protecting his friend from failure and possible ridicule. He was aware of

his friend's lack of ability for a fast, competitive game like volleyball.

Rather than see Fernando humiliated, Manuel simply refused to play. He

guessed that his friend would take the clue and do likewise. However, the

new ball game was easier and less competitive. Manuel seemed to sense that

Fernando could successfully take part without losing face.

Young as he was, Manuel intuited one of the basic lessons for helping

teach a disabled child (or any child) new skills: Introduce new

activities in small steps that the child can master quickly, to experience

success. Somehow the boy sensed that to plunge Fernando into a

volleyball game with able-bodied peers would be too difficult for him, the

pressure too great. It would draw attention to Fernando's weaknesses, not

his budding abilities. Manuel did not want us well-intending adults to

subject his disabled friend to another disheartening experience.

We learned a lot from Fernando's playmates. Children often have a

secret wisdom. If we humble ourselves and take the trouble to listen to

them with an open mind, we can learn a lot. |

| 329

|

Ball Games Where the Ball Can't Fall

For children like Fernando who have trouble catching a ball, there are

various ways to keep the ball from falling. Here are 2 possibilities.

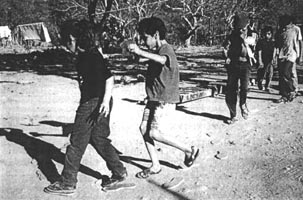

Karate and Horse-Play

In Chapter 41 we saw the example of how, in

India, Karate is used with children who have cerebral palsy - both as

excellent physical therapy and as an exciting adventure for them.

Fernando and his playmates were fascinated by Karate, and loved taking

poses, kicking high, and challenging one another in play. It was quite

remarkable how Fernando could take and hold hard positions. Self-chosen

therapy - and lots of fun!

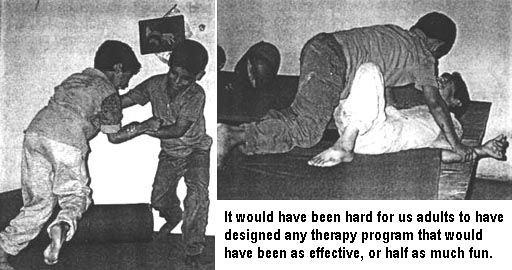

Wrestling

One of the best activities for increasing Fernando's strength and

control was developed by the children themselves in, of all places,

PROJIMO's therapy room. On seeing the large platform with padded mats,

Fernando and two of his playmates were inspired to wrestle. As the boys

tumbled and twisted this way and that, Fernando used almost every muscle

in his body, in a bizarre but surprisingly coordinated way.

|

| 330

|

Learning to Use Pictures to Communicate

The idea to use pictures to help Fernando communicate arose out of the

activities in the toy-making workshop. Manuella had asked the boys to name

an animal they wanted to make out of wood. Fernando, who cannot speak, had

difficulty communicating what he wanted. At last, making improvised signs

with his hands, he was able to tell her that he wanted a horse and rider.

But to communicate other things, at times Fernando had more difficulty.

Mari loaned Manuella a picture book of animals, from which Fernando could

pick by pointing. Creating a game, the children began to say the names of

different animals, and asked Fernando to point to them on the page. He did

this remarkably well.

Although Fernando could not read, write, or speak, he obviously had

good perception of spoken words and pictures. The team saw that, at times,

Fernando was anxious to try to communicate things that were important to

him. But he had difficulty. He could use a few simple hand signs, but the

spasticity in his fingers limited him.

Then his playmates had an idea. Why not use a series of pictures of

common things and events to help Fernando to communicate his needs? The

children had seen Andrés using a "picture board" with José, a man who had

lost his speech as result of a stroke (see

Chapter 23).

Carefully designed picture boards might work with Fernando, too. With

Fernando's help, his young friends and Mari selected lists of foods,

common objects, and various things and actions that Fernando most wanted

to "say." They organized these into groups and drew pictures of them, as

best they could.

Mari suggested they write the name of each thing below its picture.

Fernando had been unable to learn to read in school. But if, in the form

of play, he were to repeatedly see the written word associated with each

picture and its spoken name, perhaps something would stay in his mind.

When the picture board was finished, Fernando's playmates began naming

the different foods and objects drawn on the board. They asked Fernando to

point to them. He recognized and pointed at once to many of the objects,

such as FISH, CHICKEN, SPOON, TORTILLA, and ICE CREAM. He had more trouble

recognizing other objects, such as SUGAR, POTATO, and BREAD. But after

being told what they were, he did not forget. Soon he could identify every

figure on the picture-board.

Fernando enjoyed the learning game as much as his young friends enjoyed

teaching him. Thanks to the help of his playmates, the use of

picture-boards opened up a new realm of communication for Fernando.

The next step was to introduce the method to his grandmother and school

teacher. |

| 331

|

How a Caterpillar Taught Fernando to Count (with Manuel's Help)

In many areas, Fernando's mind seemed to be quick and intelligent. In

others, he had trouble learning. In school he had repeated first grade for

5 years. He still could not read or write. Learning to read numbers was

especially hard. On his fingers, he could count up to 10 (although holding

his fingers in the position he wanted was a big effort).

But Fernando had a good sense of space and proportion. He surprised his

friends with his ability to assemble some of the wooden jigsaw puzzles

made at PROJIMO. One day, Manuel challenged him to put together a puzzle

of a caterpillar, the segments of whose body were numbered from 1 to 10.

At first it was hard for Fernando to position the pieces because they

were similarly shaped. Then Manuel pointed out that they were numbered in

order. Fernando looked at Manuel in surprise, as if discovering for the

first time that printed numbers had some real use. First Manuel guided

him, and little by little, Fernando seemed to recall the numbers that had

repeatedly been taught to him in school. Fernando practiced and practiced.

Soon he was able to assemble the puzzle quickly, and to hold up the number

of fingers written on each segment of the caterpillar.

Alternating Work with Play

Although Fernando enjoyed learning to read numbers and use picture

boards with his friends, he could not stay quiet for long. Neither could

his friends. They would teach Fernando for a few minutes and then suddenly

begin to frolic or rough-house. The Playground for All Children

at PROJIMO remained a constant inspiration for new games.

Rocking Horse

Not long ago, Miguel (Conchita's husband) made a new kind of rocking

horse out of an old tire and a huge spiral spring from a dead truck. He

designed the horse to resist the wildest play of unrestrained children.

The former rocking horse in the Playground - made by hanging an old

tire with inner-tubes between 4 upright poles - was always breaking. The

new rocking horse had strong bars welded to the base of the spring, and

cast into a broad cement base that was buried in the ground. The spring,

which passed through one side of the tire, was firmly attached to the tire

with heavy iron bands. Children, disabled and not, loved the new horse

that rocked wildly up and down and in all directions. But none gave it a

more energetic work-out than Fernando and his playmates.

|

| 332

|

Improvements

With Manuel and his other playmates as his therapy assistants, Fernando

blossomed. It is hard to measure how much Fernando has gained physically

in terms of improved gait, posture, or hand control. But in terms of his

self-image and confidence, he has come a long way. Many people in the

village comment on the differences. "He used to be so withdrawn and

fearful, especially around grown-ups. Now he seems ready to take on the

world!" "He looks so much happier and full of life!"

Not only is Fernando learning new skills, but he is learning to relate

well with other people: mostly children, but increasingly even adults.

Equally important, the many children who have worked and played with

Fernando have come to accept and enjoy him as just another kid, playful

and adventurous like themselves. When they grow up, they will understand

disabled persons better than most adults. Maybe they will become agents of

change for a fairer and more understanding world.

|

|