| 311

|

CHAPTER 48

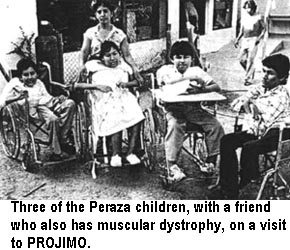

Four Siblings with Muscular Dystrophy

Lead a Program for Disabled Children

Progressive weakness. Many health and

rehabilitation workers look at muscular dystrophy as one of the more

difficult and discouraging disabilities. It tends to be familial, often

affecting brothers. It is progressive and, within current medical

knowledge, incurable. Duchenne's muscular dystrophy (the commonest type)

begins in early childhood and causes increasing muscle weakness. The child

- usually a boy - develops trouble walking, and eventually needs a

wheelchair. As the weakness progresses, his arms get too weak to push his

wheelchair or lift his hands to feed himself. Eventually, the weakness

affects his breathing and, usually in his late teens or early 20s, he

dies, often from pneumonia.

The good news. Despite all this, when given

encouragement and a supportive environment, many children with

muscular dystrophy live full and adventurous lives, even though

they may die young. In this chapter, we tell the story of a remarkable

family, the Perazas. Of their 7 children, 3 boys and one girl -

CACHITO, SÓMIMO, JUANILLO, and

DINORA - had muscular dystrophy. All were in wheelchairs

by age 10. Today, only Dinora is still alive. The boys all died in their

teens or early 20s. But, in their short lives, they did some amazing and

fulfilling things.

THE PERAZA FAMILY lives in a poor barrio of

Mazatlán city. When the parents realized that several of their children

had muscular dystrophy, they wanted to do all they could for them. In

those days it was impossible to get such children into the public schools.

Yet the Perazas felt that their children had the same right as other

children to attend school.

So the family created their own school. Helped by an exceptional social

worker, Teresa Paez, the Perazas met with families of other disabled

children in the community and collectively started their own education and

rehabilitation program for their children. The children themselves decided

what to name their group. They called themselves Los Pargos, the

name of a local fish which the elite consider inferior, although it

provides a good source of food and a livelihood for local fisher folk. |

| 312

|

Los Pargos

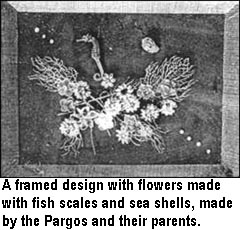

The Los Pargos school was organized as a cooperative, in which the

disabled children and parents were participating members. Most families

were quite poor. To raise money for school supplies and transport, the

families made colorful crafts to sell. Outstanding were designs with

artificial flowers, mostly made out of fish scales.

Parents and children went on work picnics to the

sea-shore where fishermen cleaned fish. They collected sackfuls of fish

scales. These they washed and sun-dried. Then they stained them various

colors and glued them together to make delicate bouquets of flowers.

With the help of Teresa Paez, Los Pargos convinced the city

government to let them use a local school building after the official

school day was over. Eventually the Education Department agreed to pay

for a teacher. But the Pargos had trouble finding a teacher who

respected and knew how to work with disabled children - until they found

Victor.

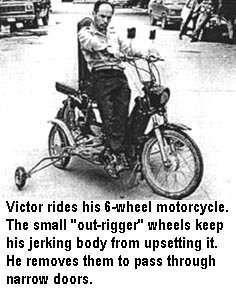

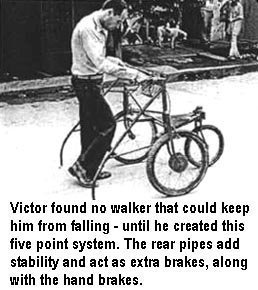

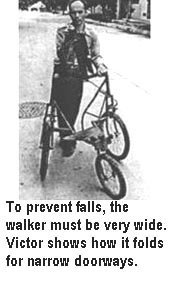

VICTOR, the teacher, was born with athetoid cerebral

palsy and began to walk when he was 8 years old. He stands and walks

with great difficulty and falls often. When excited (which he usually

is) his arms and legs jerk this way and that. He has a slight speech

problem. But Victor is avidly independent. From primary school through

college, he had to struggle to be accepted. Yet he was a gifted student.

He won a scholarship to medical school, but had to drop out because the

campus was far from home and his family could not afford bus fare. Since

then, he strove to improve his mobility. He and a friendly mechanic

invented strange and wonderful wheeled devices: walkers, motorcycles,

and even a hand-controlled auto.

Victor majored in biology and math, and has a teaching degree. For

several years he taught at the Pargos school, where he was a wonderful

example. He had loving concern for his students, yet did not pamper or

spoil them. He challenged each child to do his or her very best.

|

| 313

|

|

With a role model like Victor, many of the disabled

students became junior teachers and creative facilitators for younger

children and those who needed more assistance.

In this peer teaching process, the Peraza children took the

lead. By the time they reached their teens, their dystrophy was

advanced. Yet CACHITO and SÓSIMO, the

older two brothers, had become very capable organizers and teachers of

the Pargos. Sósimo even learned how to read and write Braille, so that

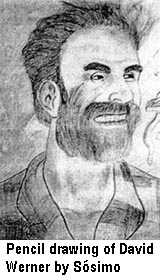

he could teach blind children. The Peraza siblings also loved to draw

and paint. With practice, they became gifted artists. One day when I

(the author) was meeting with the Pargos, Sósimo drew the pencil sketch

of me shown here.

With care and patience, the Peraza children taught other children to

draw and paint creatively. When the Pargos had enough pictures painted

and fish-scale flowers made, they periodically held a public sale.

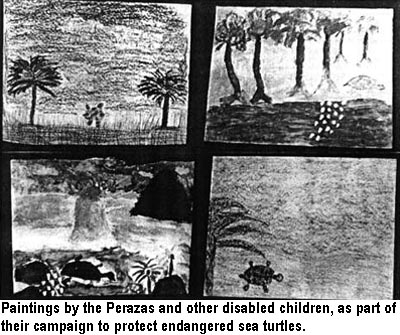

The Peraza children led Los Pargos in the defense of endangered

wildlife, with which they somehow identified. One summer, they led a

city-wide Campaign to Protect the Sea Turtles, whose

numbers were rapidly diminishing due to relentless hunting of both

turtles and eggs. The Perazas asked each Pargito (disabled

child) to do a painting of sea turtles as best as he or she could. The

resulting collection of paintings was astounding: adult turtles, turtle

eggs, and baby turtles of every size and color, swimming, dancing,

playing, laying eggs - and being hunted and butchered - in the sea and

on the beach of Mazatlán.

With the cooperation of the city authorities and local artists, a

public event was held to display the sea-turtle paintings (which sold

like hot-cakes) and to raise the awareness of the larger community. In

their defense of the sea turtles, Los Pargos won people's respect and

appreciation for the abilities of disabled children. |

| 314

|

All four of the Peraza siblings became gifted artists and

craftspersons. But Sósimo was the most outstanding. Like the

other Pargitos, he had a fascination with the ocean and its

creatures. One of his most haunting paintings is the portrait of a woman

in the bottom of the ocean. After Sósimo had died, his sister Dinora

told me he had painted it "because when people die they go to the bottom

of the ocean, and that is what makes the waves."

Evolution of Los Pargos. Eventually, Los Pargos

gained enough public attention to pressure the local public schools into

accepting some less severely disabled children. Even so, many of the

Pargitos who began to attend public schools continued to come to Los

Pargos' group in the afternoons. Several of the older Pargos took over

the management, activism, and teaching responsibilities of the program.

Among these were the Peraza siblings, whose leadership skills and

ability to motivate others grew with time, even as their physical

ability and health declined.

|

This photo of Sósimo in his late teens reflects his

combination of artistic ability, self-determination, and his radiant

joy in the creative process. I wish all children with muscular

dystrophy, and their parents, could have had a chance to know and

learn from Sósimo and his family. |

As the years went by, Los

Pargos grew and expanded. Children with all kinds of disabilities -

physically disabled, mentally handicapped, epileptic, deaf, blind,

and multiply disabled - came daily from all parts of the city.

Transportation was a big problem. At last, with money they earned

plus donations by well-to-do patrons in the city, the Pargos were

able to buy a second-hand bus - which they named the Pargobus.

Periodically the Pargobus would make trips to PROJIMO, in the

village of Ajoya, about 100 miles from Mazatlán. The outings served

as visits to the countryside and a chance for the children to enjoy

the games and equipment in the Playground for All Children. The

visits also provided an opportunity for children to be fitted with

wheelchairs, orthopedic appliances, special seating, and other

assistive devices. Again, the young Perazas often played a leading

role in helping to organize these trips. It was amazing what these

four youths with muscular dystrophy managed to do, and the pride and

joy they took in doing it, even as their physical condition

gradually deteriorated.

But for all their creativity and problem-solving skills, they

could not halt the progress of the disease. Over a period of several

years, one after the other of the 3 Peraza brothers died from

pulmonary problems. Today only their sister, Dinora, is still alive.

But the dignity, caring, and leadership skills they

developed and shared with their peers live on. |

|

| 315

|

At present, Los Pargos is managed and run

by disabled graduates of the program, some of whom are continuing with

their formal schooling and some of whom have jobs. (One of the first

members of the Pargos, Miguelito, who has physical and speech

difficulties, works in an automobile repair shop, skillfully taking

dents out of damaged cars.) Occasionally, the disabled youths who run

the program call on the assistance of special educators, teachers,

doctors, and therapists when they think their help is needed. But

overall, the group takes pride in its autonomy and independence.

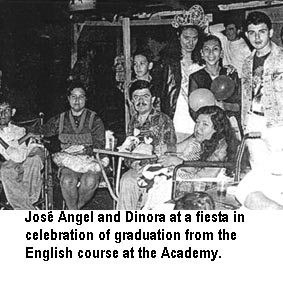

DINORA BECOMES AN ENGLISH TEACHER - WITH HELP FROM JOSÉ ANGEL

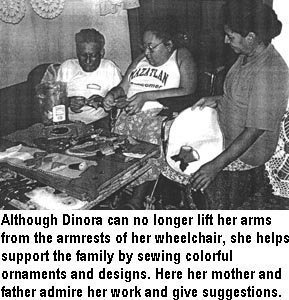

Recently I (the author) visited the Peraza home and had a long talk

with DINORA. She is now almost 20 years old. Her muscle

weakness has progressed so that she can not lift her arms. However, she

creates lovely hand-sewn crafts by balancing her forearms on the

armrests of her wheelchair. She still is active with Los Pargos.

Although travel by bus to the Pargos center is now too difficult for

her, she teaches English to several of the Pargitos who come to

her house.

I asked Dinora how she had learned to teach English. She said she had

studied at the ACADEMIA DE INGLES THE GOLDEN GATE, a few blocks

from her home. Her father took her there daily in her wheelchair.

"David, I wish you could meet my teacher, who runs the Academia,"

said Dinora. "He's a wonderful person. He's disabled."

"Is his name José Angel?" I guessed.

"Yes!" said Dinora. "Do you know him?"

"Years ago, when he was a boy, we took him to Shriners Hospital in

California for surgery," I replied. "I haven't seen him for years, but I

heard he was teaching English in Mazatlán."

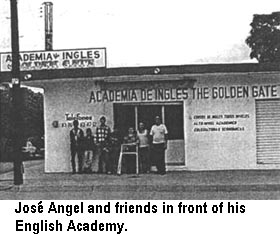

That afternoon, Dinora's father took me to visit JOSÉ ANGEL

Tirado. The Academy, next to his father's house, is a great success,

with 3 classrooms and 3 teachers. José Angel, who has a rare

degenerative bone disease, made many trips to Shriners Hospital in

California for surgery when he was a child and an adolescent. Now he has

artificial hips and knees. On his many visits to the USA he learned a

lot of English.

Once back in Mexico, José Angel began tutoring classmates in English,

and he eventually started teaching small groups. He was a good teacher

who knew how to make learning fun. More and more students wanted him to

teach them. So, his father rented a room next door, and that was the

start of the Academy. Today, there are 80 students and a long waiting

list. Financially, the Academy has been so successful that José Angel

paid for a full renovation of his father's house. He charges enough to

make a good living. But for disabled people who want to study at

the Academy, he gives full scholarships. |

| 316

|

| A close community. The

Peraza family and the Pargos, together with disabled role models and

teachers and like Victor and José Angel, form a close community of peers

and friends who help, challenge and provide inspiration to one another.

Despite their difficulties, there is an aura of warmth and even joy

about the Peraza home. Every time I visit the Peraza's, I come away with

new energy and hope - not so much hope for a wonder drug to cure

muscular dystrophy (although that would be marvelous), but rather, hope

for humanity. The Peraza family and their children with

muscular dystrophy somehow found unusual strength and vitality. The

children made the most of their lives, however short, finding pleasure

in helping others in need. We can learn a lot from them.

Their spirit lives on. Three of the four Peraza

children are no longer physically present. But each of them, until very

shortly before his death, found great pleasure and dignity in helping

other children in need. The remarkable abilities they developed were not

limited to their artistic creativity. They inspired disabled and

non-disabled people to do their best, and to bring out the best in one

another. Their short lives, far from being tragic, were full and

rewarding - with joys, sorrows, challenges, and adventures - as life

should be. |

| 317

|

Innovative Therapy Aids for Other Children with Muscular

Dystrophy

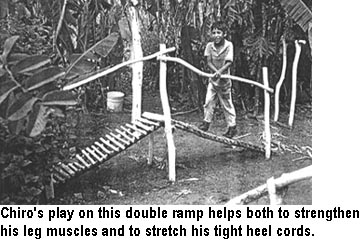

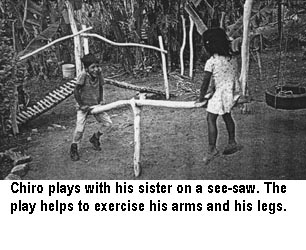

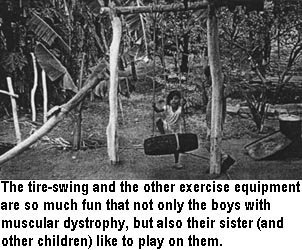

CHIRO and RICARDO are two brothers

with muscular dystrophy, from a village called Limón. (Child-to-Child

activities to help school children be more accepting of these boys are

described in Chapter 45, on page 300.)

When their parents brought the brothers to PROJIMO, they were at a loss

as how to help their sons. They had taken the boys to a rehabilitation

center in the city where they had been given a number of exercises to

stretch their tight heel cords and to try to maintain their muscle tone.

But the boys whined and complained when their parents tried to apply the

exercises, which were anything but fun.

At PROJIMO, Mari encouraged Jesús and some of the other disabled

children to introduce Chiro and Ricardo to different activities in the

Playground for All Children. Playing on the ramps and swings, the boys

engaged in exercises that stretched their tight heel-cords and helped

them use many muscles of their bodies. And the boys enjoyed it.

Inspired by the PROJIMO playground, the boys' father decided to build

at home some of the playground equipment that his sons most enjoyed, and

which provided necessary exercise. The following photos show some of the

equipment he built, with the help of his sons, behind the family hut in

their village.

|

| 318

|

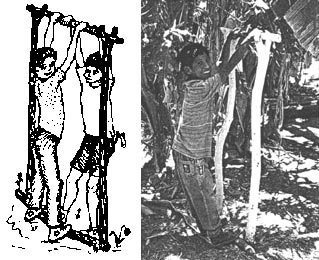

Heel-cord stretcher. This apparatus, invented by

their father, also helps Ricardo and Chiro stretch their tight heel

cords. This is done by stepping on the pole on the ground with the front

part of the foot, and then rocking back and forth.

The device also helps exercise the child's shoulders, arms and hands.

Standing with the fore-foot on the pole on the ground helps to

stretch tight heel-cords. The bend in the pole - so that it slants down

to the center from either side - helps combat inward (varus) deformities

of the feet.

|

|