CHAPTER 45

Starting Village-Based

Rehabilitation Activities

TOP-DOWN OR BOTTOM-UP?

Around the world today there are many examples of what have sometimes been called 'community-based rehabilitation programs'. Some of these programs are 'top down'; others are 'bottom up'.

Top-down: Chain of command

Top-down programs or activities are mostly planned, started, organized, and controlled from outside the community: by government, by an international organization, or by distant 'experts'. And the local leaders are usually persons in positions of authority, influence, or power.

Bottom-up: Equality in decision-making

Bottom-up programs or activities are those that are largely started, planned, organized, and controlled locally by members of the community. Much of the leadership and direction comes from those who need and benefit most from the program's activities. In brief, the program is small, local, and 'user-organized'.

Community participation is important to both top-down and bottom-up programs. But it means something different to each:

In top-down programs, people are asked to participate only in ways that have already been decided from above. For example, a decision might be made by a team of foreign specialists that certain persons in each community be selected as 'local supervisors'. The local supervisors are taught several pre-decided 'packages' of cookbook-like information. Each supervisor then instructs a given number of 'local trainers' (family members of the disabled) how they 'must train' each particular disabled person. Thus 'community participation', from the viewpoint of the experts, means 'getting people to do what we decide is good for them'.

In bottom-up programs, 'community participation' means something else. The program develops within a village or neighborhood, according to the needs and wishes of its members. It may take an outsider with some knowledge in rehabilitation and skill in organizing people to help get things started. But it is the people themselves, especially disabled persons and their families, who make the decisions about their own program. They can learn from other programs and from the experts. But they do not simply copy or follow others. They pick and choose from whatever advice and information they can get in order to plan activities that fit the needs and possibilities of their particular village, and their particular children.

There are advantages and disadvantages to top-down and bottom-up. For a central government, a standardized, top-down approach is easier to introduce, administer, and evaluate in many communities at the same time. But in primary health care, it has become clear that top-down programs frequently fail or have serious weaknesses, mainly because they do not have enough popular leadership, understanding, and personal commitment. These are especially important for rehabilitation. Every disabled child is different and has her unique combination of needs. An imaginative, problem-solving approach is essential. If decisions and plans come pre-packaged from above, rehabilitation measures often do limited good and sometimes even harm.

In a bottom-up approach there is a greater sense of equality, and of arriving at decisions together. People do not just follow instructions. They consider suggestions. They want to know why. This greatly increases the chances that exercises, aids, and activities will really fit the individual needs of the child. It also makes rehabilitation more interesting, meaningful, and valuable for all concerned. It helps both parents and children become more independent.

A bottom-up approach to rehabilitation has the advantage of flexibility and adaptability that comes from being organized and controlled locally. Planning is a continuous learning process that responds to the changing needs, difficulties, and possibilities within the community. Especially when disabled persons and family members play a leading role, participants at every level are likely to develop a spirit of respect, friendliness, and equality that keeps a program human and worthwhile.

Above all, a bottom-up program organized by those it serves, decentralizes and redistributes power: people who have been powerless begin to find strength through unity. You can never be sure where things may lead, how far people may go in terms of taking charge of their own lives or in demanding their rights.

![Logo of PROJIMO [shade]](images/dwe002g04704.gif)

On the following pages we look at community rehabilitation activities and programs from a 'bottom-up' approach in a village situation. This is where our own experience lies. For a different approach with more of the planning from above, we suggest you see the World Health Organization's Training Disabled Persons In the Community along with the supplementary materials (see Page 637). For a sharp analysis of different approaches, read Mike Miles' Where There Is No Rehab Plan (see Page 641).

STARTING IN A VILLAGE -WHERE TO BEGIN?

Rehabilitation of disabled persons within a village or neighborhood usually has two major goals:

- To create a situation that allows each disabled person to live as fulfilling, self-reliant, and whole a life as possible, in close relation with other people.

- To help other people-family, neighbors, school children, members of the community-to accept, respect, feel comfortable with, assist (only where necessary), welcome into their lives, provide equal opportunities for, and appreciate the abilities and possibilities of disabled people.

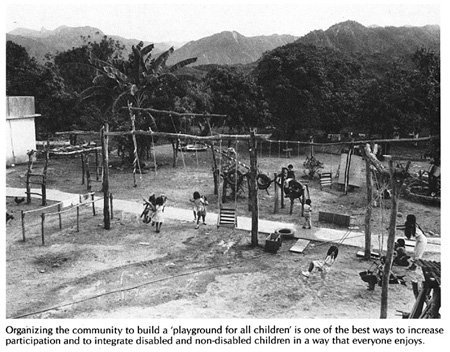

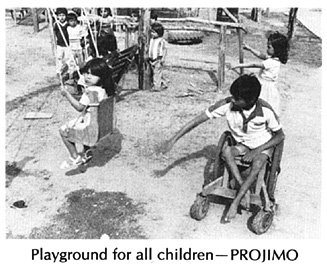

One of the best ways to bring about better understanding and acceptance of disabled people is to involve both disabled and non-disabled persons in shared activities. The next few chapters discuss selected community activities that can help improve people's understanding and respect for the disabled. These can be introduced either as part of a rehabilitation program, or independently by concerned persons such as parents, school teachers, or religious leaders. Some of these activities, in fact, have proved to be good ways to create interest and open discussion with local people about starting a small community-based program.

There are many possibilities for getting people in a village or neighborhood more actively involved. Often a good way to start is to call a meeting to bring together disabled persons and family members of the disabled. Sometimes one or more leaders in the community happen to have a child or close relative who is disabled. These persons, with a little encouragement, may take the lead in organizing other families with disabled children, or in starting a local rehabilitation program.

It makes sense to start where people express their biggest concern. For example, in Peshawar, Pakistan, a community program for retarded children was started because families of these children expressed a strong need. In Nicaragua, a group of disabled revolutionaries with spinal cord injuries started a program to produce low-cost wheelchairs to meet their particular needs. In Mexico, physically disabled village health workers started a community program for disabled children and their families. Today, these 3 programs have all expanded their coverage to include a far wider range of disabilities than they started with.

Some children have several disabilities, so it is hard to limit attention only to certain ones. We must try to meet the needs of the whole child, within the family and within the community. However, it often works best to start in a small and fairly limited way, wherever people are ready. Let things grow and branch out from there, as new concerns arise and new people become involved.

Who gets things started?

Within a community or neighborhood there will often be persons eager to become involved in starting rehabilitation activities or even a program. All it may take is something to 'spark the idea'. This spark can be in the form of a person, a pamphlet, or even a radio program that triggers people's imaginations with ideas or basic information.

For example, we know of one village medic, herself disabled by polio, who received a WHO magazine with an article on "Rehabilitation for All.'' As a result, she began to organize the villagers to build a simple rehabilitation playground. In a similar fashion, CHILD-to-child activity sheets have sometimes inspired teachers to conduct activities that help school children to prevent certain disabilities or to behave toward disabled children in a more friendly, welcoming way.

Often, to get things started, it takes a person with some background in rehabilitation and in community work, to stay for a while in a village or neighborhood. Her role is to bring together people with similar needs, helping them to form a plan of action and to obtain the information and special resources they need.

Such a 'resource person' is sometimes called an 'agent of change'. She need not be a highly-trained professional in rehabilitation or social work. In fact, persons who have professional degrees often have the hardest time accepting that parents and disabled persons can and should be the primary workers and decision makers in a community rehabilitation program.

What is necessary is that the agent of change be someone who respects ordinary people, and is committed to helping them join together to meet their needs and defend their rights.

The agent of change should be a counselor, not a boss; a provider of information and choices, not orders or decisions. Especially when such a person comes from outside the community, her role is to stay in the background, to help the people make their own decisions and run their own program. At all costs she avoids taking charge.

Staying in the background, however, is easier said than done, especially for an agent of change who is deeply committed. To make sure that a program is run by the people, not by outsiders, it is often a good idea that agents of change and any visiting professionals not be present all the time. Instead, they should encourage the program to continue without them. Perhaps the final test of an agent of change's success is to leave the community forever, without her absence being much noticed. These ideas are said beautifully in this old Chinese verse:

To help start a program for the disabled, it often works out better if the agent of change is also disabled. This helps make the outsider an insider.

Disabled persons as leaders and workers in rehabilitation activities

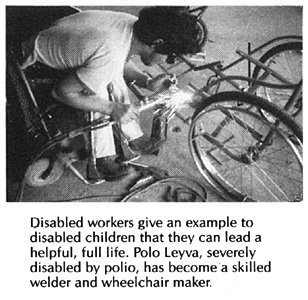

Some of the most exciting and meaningful community rehabilitation activities in various parts of the world are those that are led and staffed by disabled persons themselves. When the leaders and workers in a program are disabled, they can be excellent role models for disabled children and their parents. When they see a team of disabled persons working together productively, doing more to help other people than most able-bodied persons do, and enjoying themselves in the process, it often gives both family and child a new vision and hope for the future. This alone is a big first step toward rehabilitation.

Another reason for recruiting leaders and workers who are mostly disabled persons (or their relatives) is that they are more likely to work with commitment, to give of themselves. From their own experience, they understand the problems, needs, and possibilities of disabled persons. Because they, too, have often suffered rejection, misunderstanding, and unfair treatment by society, they are more likely to become leaders in the struggle for a fairer, more fully human community. Their weakness contributes to their strength.

| Examples of community rehabilitation programs run by local disabled persons are in Chapter 55. |

Kinds and levels of village-based activities

There is no formula or blueprint for starting a village rehabilitation program. How things get started will depend on various factors: the size of the village, the number and nature of disabled children, the interests and talents of parents and other persons, the resources available, the distance and difficulties for getting specific rehabilitation services elsewhere. Also consider the possibilities for getting assistance (voluntary, if possible) from physical therapists and other rehabilitation professionals, craftspersons, health workers, schoolteachers, and others with skills that could be helpful.

If rehabilitation is ever to reach most of the children who need it, most rehabilitation activities must take place in the home with the family members as the primary rehabilitation workers. And even where plenty of money and professional services are available, the home and community are still the most appropriate place for most of the rehabilitation of most disabled children.

For home-based rehabilitation to be effective, however, parents need carefully prepared and selected information, friendly encouragement, and assistance. And at times they will need back-up services of rehabilitation and medical workers with different kinds and amounts of skills.

A good arrangement, perhaps, is a referral chain, starting with rehabilitation in the home with guidance from a small community center run by local, modestly trained workers. If possible, the center has close links with the nearest low-cost or free orthopedic hospital and professionally-run rehabilitation center, to which the relatively few children with disabilities requiring surgery or complex therapy can be referred. Outside professionals (orthotists, therapists, and others) can help by making periodic teaching visits to village rehabilitation centers. They can also invite village workers to visit and apprentice with them in their city shops and clinics. (Apprentice means to learn by helping someone more skilled.)

Some villages will be too small or lack the resources to start their own community rehabilitation center. However, it has been found in several countries that once a modest center in one village opens, the word spreads. Disabled children with family members soon begin arriving from surrounding villages. In time the rehabilitation team may be able to help disabled persons and their families in neighboring villages to organize their own sub-centers. Disabled workers from these sub-centers can learn by 'apprenticing' at the original center.

The above 'ideal' is more or less the way Project PROJIMO in Mexico works, although with certain difficulties and obstacles.

The role of a villager-run rehabilitation center

Some of the most important rehabilitation activities take place with the family in the home. Others take place in the school, the marketplace, the village square, and, when necessary, in the nearest orthopedic hospital. The key to helping all this happen can be the village rehabilitation center.(See the next page.)

A village rehabilitation center run by modestly trained disabled workers, together with the families of disabled children, can provide a wide range of services. These may include training and support of families, community activities, non-surgical orthopedic procedures, and making orthopedic and rehabilitation aids. The program need not try to do everything at first, but can start with what seems most important and gradually add new skills and activities as needs and opportunities arise.

Eventually, a community team can gain considerable skill in many areas. For example, the village team of PROJIMO is able to adequately attend the needs of about 90% of the disabled children it sees (except for blind or deaf children for whom its services are still not adequate). Only about 10% need referral to orthopedic hospitals or larger rehabilitation centers. Visiting experts have found that at times the therapy or aids provided by PROJIMO are more helpful than those previously provided to the same children by professionals in the cities.

The chart on the following page gives an idea of possible activities and functions of a village rehabilitation center. It also lists activities of possible 'sub-centers' in neighboring villages, as well as referral and support services needed from urban orthopedic and rehabilitation centers, and outside specialists.

POSSIBLE ACTIVITIES AND FUNCTIONS OF REHABILITATION CENTERS AT DIFFERENT LEVELS

Sub-centers in neighboring villages

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| VILLAGE REHABILITATION CENTER(serving

children and their families from a group of villages)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Urban orthopedic and rehabilitation referral centers, and outside specialists

|

The importance of community-run rehabilitation centers

In an attempt to get the focus of rehabilitation out of big institutions and into the home, some community-based rehabilitation programs have tried to manage without any kind of local rehabilitation centers. 'Local supervisors' make home visits and work directly with the families of the disabled. However, when additional assistance or aids are needed, the local supervisor often has nowhere to turn. She has to send the disabled person to professionals in the city. For reasons of distance, cost, fear, or failure of the support system, these referrals too often do not work out. As a result, rehabilitation is often incomplete, and people get discouraged.

Of course, referral to large city hospitals or centers will still be important for selected individuals. However, there are several strong arguments in favor of setting up a small village or community-based rehabilitation center run by local concerned persons:

- It is a visible, practical, low-cost base for coordinating rehabilitation activities in the home, and for providing back-up services outside the home.

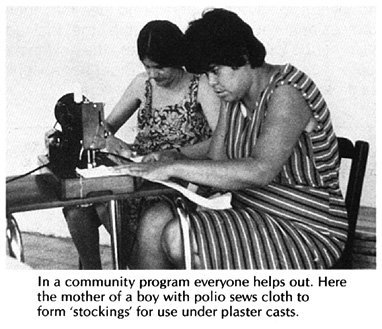

- It can produce a wide range of rehabilitation equipment and aids quickly and cheaply, using local resources, with participation of families, schoolchildren, and local craftspersons, when possible.

- It can include a 'playground for all children' and organize activities to encourage understanding and interaction with the disabled.

- It can provide meaningful work and training experience for local, otherwise often untrained and unemployed disabled persons. It gives the families of disabled children and other villagers the chance to see what a useful, helpful, and rewarding role disabled persons can have in a community.

- Although the best place for day-to-day rehabilitation is often the home, there are families for whom this may be very difficult. These include families in which one or both parents have left or are dead, or have drinking problems, or where step-parents or other family members are cruel to the child, neglect her, or abuse her sexually (a fairly common problem). In many homes, the family does the best it can. But the extra work of trying to care for a severely disabled child may simply be too much for the family that has to work long hours just to survive. Under any of these circumstances, special care at a community center may be of enormous benefit to both the child and the family.

- If many small community centers join to form a 'network', they can exchange ideas and learn from each other. Or different centers can 'specialize' in producing different supplies or equipment. For example, one village center might make wheelchairs, another toys, and another low-cost plaster bandage for casting. Then different centers or programs can supply each other at low cost.

| Home-based rehabilitation often works much better with the help of a local, community-run center. |

How small, local programs spread to new villages and areas

Bottom-up programs tend to spread through popular demand. As the news of the program travels from family to family and town to town, even a small program based in a single village can reach far in its impact. For example, Project PROJIMO is based in a village of less than 1000 and has a staff of a dozen disabled villagers. In its first 4 years, PROJIMO has attended to the needs of over 1,000 disabled children from over 100 towns and villages and the slums of several large cities. (Since roughly one child in every 100 people is moderately to severely disabled, PROJIMO is in effect serving a population of over 100,000.)

There are various ways that bottom-up or 'people-centered' programs tend to spread. We speak of their growth as 'organic' because they grow and spread in a living, whole sort of way, like seeds into trees.

In Project PROJIMO, some of the young people from neighboring communities, who first come for rehabilitation, decide to stay and to work for a while in the program. In the process they learn skills which they can use to help in the rehabilitation of other persons when they return to their own communities. In some cases, other villages and village-based health programs have sent young disabled persons to apprentice with PROJIMO for several months, in order to help start similar activities on return to their communities.

Another people-centered program that started small and has spread to many other towns is the Community Rehabilitation Development Program in Peshawar, Pakistan. This is discussed on Page 520.

ACTIVITIES IN THE COMMUNITY TO WIN INTEREST AND UNDERSTANDING

Group activities in a village or neighborhood can help improve understanding of and interaction with the disabled children. Four types of activities that have proved especially useful are discussed in the next 4 chapters:

| A 'Playground for all children' | |

| CHILD-to-child activities | |

| Popular theater | |

| A children's workshop for making toys |

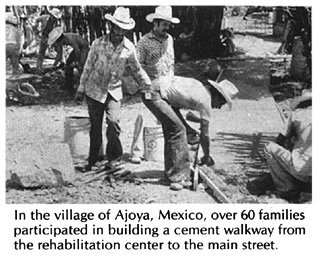

Any of these activities may be used to gain people's interest and involvement when starting a community rehabilitation program. Or they can be used to increase understanding even where no special program is planned. For example, the workers in a village with a rehabilitation center can visit neighboring villages and put on skits or puppet shows about disability prevention. They might also talk with school teachers, local health workers or concerned parents about developing CHILD-to-child activities, or organize local children to build a 'playground for all children'. Project PROJIMO took a truckload of school children to a neighboring village to help the children there build their own playground. Nearly 100 children and adults built the playground in one day.

After these 4 chapters, we will explore other aspects of social integration and opportunities for the disabled.