|

| 239

|

CHAPTER 38

Osvaldo:

A Triplegic Boy with Many Challenging Needs

OSVALDO's childhood was like that of many boys in

a poor urban community. He lived with his ailing mother on a hill on the

outskirts of Culiacan, the state capital of Sinaloa, Mexico. His father

had abandoned the family years before. His mother worked in a factory, for

wages so low that sometimes there was little to eat. Osvaldo went to

school, but he often skipped classes to do odd jobs or to play.

When he was 13 years old, an event happened that drastically

changed Osvaldo's life. He was playing with friends on the

roadside outside the family hut, when a truck parked at the top of the

hill, and the driver got out. Then the hand-brake failed, and the truck

rolled down the steep dirt road toward the children at play. It suddenly

pitched off the narrow road, straight into the children. One child was

killed, four were injured. Because the driver had not been in the truck

(and had slipped the police a bribe) he was not held responsible.

After he was hit, Osvaldo - dazed and bleeding - tried to stand up. But

he could not move his legs or his right arm. Neighbors took him to the

hospital. The doctors found his spinal cord was crushed at

mid-back level (T6). He had a double fracture of his right leg,

above and below the knee. His right shoulder was broken and dislocated,

with nerve damage that left his right hand and arm paralyzed.

So it was that, at age 13, Osvaldo became triplegic (paralyzed

in 3 of 4 limbs). He had lost all movement and feeling in his

lower body and had no urine or bowel control. In

the hospital his broken spine was stabilized surgically with metal rods.

(Fortunately, Osvaldo's mother had social security insurance which covered

most of the medical expenses.)

On his release from the hospital, Osvaldo was taken by ambulance to his

home. Unfortunately, neither he nor his mother had been given instructions

about prevention of pressure sores and urinary infections. So, day after

day, Osvaldo lay on his back on a burlap cot without moving. A month

later, when a nurse made a home visit, she found that his back, buttocks,

and heels were covered with pressure sores. The hospital

then provided an "egg crate" foam mattress, and a nurse instructed the

boy's mother to "Turn him frequently from side to side."

But this was easier said than done, as his mother soon discovered.

Osvaldo had sunk into severe depression which expressed itself as

anger, directed mostly at his mother. His paralyzed right hand

was extremely sensitive: it gave him unbearable, burning pain, especially

when it was moved. He rested it over his chest without moving it for weeks

and months. In time, his right arm became stiffly fixed in front of him.

He was so afraid of having his painful hand touched or moved that

he refused to let his mother get near it. Whenever she tried to

move him he would weep and protest. Using his good left arm, he fiercely

fought off her attempts to turn him on his side. Because of his lack of

urine and bowel control, she had a hard time keeping him clean. |

| 240

|

PROJIMO TO THE RESCUE

In November, 1991, on a visit to the capital city, two disabled

workers from PROJIMO learned about Osvaldo and visited his home. Five

months after his accident, the boy was near death. Emaciated, anemic,

and very depressed, he had deep pressure sores, a urinary infection and

chronic fever. His doctors had not stressed the importance of drinking

lots of water to reduce the risk of urinary infection. Adding to the

danger, they had not changed him from a permanent catheter

(urine-draining tube) to intermittent catheterization (see

page 147). His dark urine had so much

crud in it that the catheter often clogged. His pressure sores, which

his mother did her best to clean and bandage, were infected and had

black necrotic (dead) areas.

The worst sores were on the back of his ankles. They formed after the

visiting nurse - worried about the sores on his heels - told his mother,

"Keep a rolled-up towel under his ankles." His mother had carefully

followed the nurse's orders. Four months later (when the PROJIMO workers

visited the home) deep sores had formed where the towel was still

obediently positioned. The sore under the left ankle was so deep that it

bared the Achilles tendon.

This was a powerful lesson for the PROJIMO workers. They saw the

danger of simply giving cookbook-like instructions without explanations.

On the contrary, it is important to:

Help people to fully understand the reasons for

doing things, so that they are able to

make well-informed decisions, based on their own observations

and changing needs.

Further complicating Osvaldo's condition was his delicate, often

angry mood, his fear of pain or injury, and the excruciating sensitivity

of his paralyzed right hand. Yielding to his tearful protests, his

mother had given up attempting to turn him onto his side or belly. So,

for five months he had lain on his back, his pressure sores getting

larger and deeper, and his body growing as stiff as a board.

On seeing Osvaldo, the PROJIMO workers felt that - due to the

difficult combination of physical and emotional needs - more might be

accomplished in their small community rehabilitation center than in the

home. They invited him and his mother to spend a while at PROJIMO. At

first, Osvaldo was afraid to leave home ... or even to be moved from his

cot. But the warmth and concern of the PROJIMO workers gave him a new

sense of hope. Gathering courage, he accepted their offer. The next

morning, with Osvaldo lying on a foam mattress in the back of a station

wagon, the group made the 4-hour trip to PROJIMO.

The Need for a Creative and Loving Approach

The

complexity of Osvaldo's needs called for very caring rehabilitation and

innovative assistive equipment. His urinary infection and sores required

urgent attention. For the former, the team gave him antibiotics and

encouraged him to drink lots of fluids. However, he

often refused to drink, even when we explained its importance. Since

Osvaldo's favorite drinks were orange juice and hot chocolate, we

pampered him with all of these he could drink. As his urinary infection

got better, so did his mood and appetite. The

complexity of Osvaldo's needs called for very caring rehabilitation and

innovative assistive equipment. His urinary infection and sores required

urgent attention. For the former, the team gave him antibiotics and

encouraged him to drink lots of fluids. However, he

often refused to drink, even when we explained its importance. Since

Osvaldo's favorite drinks were orange juice and hot chocolate, we

pampered him with all of these he could drink. As his urinary infection

got better, so did his mood and appetite.

The team put Osvaldo on a high calorie, high protein, high

iron diet. Improving his nutritional status and blood level

would help to heal his pressure sores, and fight off the urinary

infection.

|

| 241

|

Managing Osvaldo's Pressure Sores - and Lifting His Spirits

The next job was to find a way of taking the pressure off of

Osvaldo's pressure sores. To manage the sores on the back and

buttocks, PROJIMO usually builds a gurney, or trolley (narrow wheeled

bed), on which the person can lie face down. That way he can wheel

himself around, and energetically work and play. Keeping active not

only makes lying face down for long periods more tolerable, but it

also stimulates circulation, which speeds healing.

With Osvaldo, however, lying face down was not an easy matter. From

having lain flat on his back for months, his entire body had become as

stiff as a board. Also, his paralyzed right arm was almost "frozen,"

with his forearm over his chest. Both the shoulder and hand were so

super-sensitive that he would howl even before someone touched them.

The first job was to win Osvaldo's trust and to involve him in the

problem-solving process. The team tried to give him a sense of control

that would help him overcome his fear. Often, it seemed that

his fear of the pain was worse than the pain itself.

Certainly it made the pain worse.

On discussing Osvaldo's wishes and needs with him and his mother,

it became clear that the management of his sores needed an

integrated plan to lift both his body and his spirit. His

various physical and emotional needs needed to be answered in a

"whole-person," or holistic, way. The group agreed that the major

short-term objectives with Osvaldo were:

| to figure out ways to get the pressure off Osvaldo's sores for

prolonged periods and, as soon as possible, to find a way for him to

lie face down without lying on top of his stiff, hypersensitive

right arm and hand; |

| to help him regain flexibility of his hips and knees, so that he

could begin to sit: first in bed, and later (after his pressure

sores healed) in a wheelchair; |

| to correct the foot-drop (contracture of the heel cords) that

had begun to form; |

| to help him increase the strength and ability of his useful

(left) arm - a greater challenge because he had been right-handed; |

| to design mobility aids that Osvaldo could move and steer with

only one arm; |

| to provide a range of enjoyable and useful activities so as to

encourage self-care, self confidence, and more independence; |

| while doing all of the above, to provide a friendly,

understanding, stimulating, entertaining, and adventurous

environment - to help Osvaldo pull out of his depression and

rediscover joy in life, the will to live, and ability to love. |

Talking with Osvaldo was not easy. It took time for him to gain

enough confidence in himself and in others to speak seriously. What

seemed to distress him most was his sense of powerlessness and total

immobility. He feared remaining dependent, not being able to do

anything for himself, to move, or to go anywhere without help.

Therefore, helping Osvaldo learn to do more for himself,

manage his personal body functions, and move under his own power

were seen as urgent goals which could contribute to his healing in

many ways.

In these pages, we will not describe all the aspects of Osvaldo's

rehabilitation - rather we will focus on several of the most

innovative aids and activities. |

| 242

|

Innovations For and With Osvaldo

To help meet the various objectives of Osvaldo's rehabilitation -

or revitalization - the PROJIMO team designed a number of innovative

devices. They will be described here in the order in which they were

created and used.

It is important to note that most of these innovations were

developed with the active participation of Osvaldo himself.

In the process, this 13-year-old boy acquired a much clearer

understanding of his body, its unusual needs, and how to meet them. He

began to rediscover and become friendly with his own mysterious body,

and to increasingly take charge of his own rehabilitation and care.

Soon he was reminding and guiding his attendants (especially his

mother) about how to position him and where to place padding to

prevent pressure sores. His testing, criticism, and suggestions for

improvements of devices became a valuable part of the innovative

process. As he became an active participant in the design of his own

equipment, he gained new confidence, lost much of his fear of trying

new things, was less fretful, and gradually became again a friendly,

playful boy - although strangely perceptive and wise for his age. (He

avidly read Disabled Village Children and gave suggestions

for the rehabilitation of other children.)

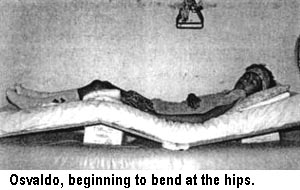

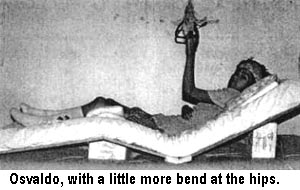

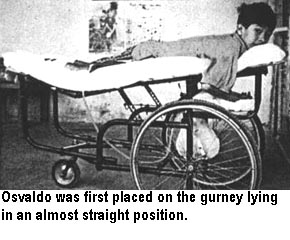

AN ADJUSTABLE BED

- To help reduce pressure over sores, bend his stiff body, and prepare

him for sitting

Complexity of the problem: Clearly, for

rapid healing of his pressure sores, Osvaldo needed to stop lying on

his back and start lying on his belly or side. However, the team

realized the need to move toward this slowly, at a pace the boy could

tolerate and control. Osvaldo was terrified of being shifted to a new

position that might trigger the pain in his hypersensitive shoulder

and hand. It had taken his last bit of courage just to come to

PROJIMO, and the team did not want to push him too hard or fast. In

the first days, especially, it was essential that his experience at

PROJIMO be as reassuring and uplifting as possible. Therefore the

team, together with Osvaldo and his mother, tried to think of ways to

reduce the pressure on the sores on his back and buttocks - and to

help him regain some flexibility in his hips and knees - while still

lying face up.

Partial solution: To reduce pressure over

the bony areas with sores, Osvaldo was laid on a double foam

mattress, the lower one thick and fairly firm, the upper one

quite soft. To help speed healing, the sores were packed daily with a

paste made of bees' honey and sugar (see

page 156).

From lying flat on his back for so long, Osvaldo's hips and knees

had grown so stiff (with extension contractures) that they almost

would not bend at all. Bending exercises were introduced. What was

needed, however, was prolonged, very gentle stretching. It would have

helped to have a hospital bed that could be gradually cranked up into

a sitting position, slowly bending the hips and knees. But such a

costly item was out of the question.

Partial solution: an adjustable, hinged plywood bed board.

Materials: 1 sheet plywood; 2 strips old cloth (about 6

inches wide); white glue.

Construction: A piece of plywood the size of the cot was

cut in three pieces based on Osvaldo's body measurements (A=feet to

knees, B=knees to hips, C=hips to head). The plywood sections were

then joined together with cloth hinges made with strips of old towel

and white glue. |

| 243

|

|

- A metal triangle, hanging from a rope over Osvaldo's bed,

allowed him to lift himself up periodically with his good arm.

This took pressure off his back, and also helped strengthen his

arm.

- By putting padding under Osvaldo's knees, some of the weight

could be taken off his backside.

- This padding reduced the pressure on his buttocks and lower

back, where he had some of his worst sores.

- Padding was also placed under his lower legs, to take pressure

off his heels and ankles.

- By putting boxes of different sizes under the bed-boards, the

angle of his hips and knees could gradually be increased.

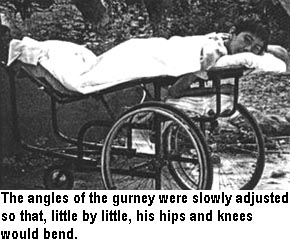

Results: Flexibility of Osvaldo's body

returned surprisingly quickly. Within a few weeks, both his hips and

knees flexed to almost to 90 degrees. Also, being able to move into

a partly sitting position allowed the boy to do more things more

easily (eat, read, draw pictures, and take part in what was going on

around him). His disposition improved accordingly. And his pressure

sores began to heal.

Technical problem: With repeated

removal and replacement of the hinged plywood bed-board between the

two foam mattresses, the cloth hinges began to tear loose.

Solution:hinges made of thin cord. As

an experimental alternative, hinges were made using cord (thick

string). The cord passes through small holes in the edges of the

plywood sections.

Results of cord hinges: These hinges

were as quick and easy to make as the cloth hinges, and they could

be used at once (whereas several hours of drying time were needed

before the cloth-and-glue hinges could be used). The cord hinges are

stronger and hold up longer than the cloth hinges (although this

clearly depends on the relative strength of the cord, the cloth, and

the glue). |

| 244

|

A SIMPLE AID FOR ACTIVE CORRECTION AND PREVENTION OF FOOT-DROP,

IN BED

The problem: From lying in bed so long,

Osvaldo had begun to develop contractures of his heel cords

(Achilles tendons). This made it difficult to bring his feet up to

90 degrees. He wanted to do this with the dream of someday standing

or even walking - or at least so his feet would be in a good

position and he could wear shoes.

Osvaldo wondered if there was some way he could do the exercises

by himself to regain the flexibility of his ankles.

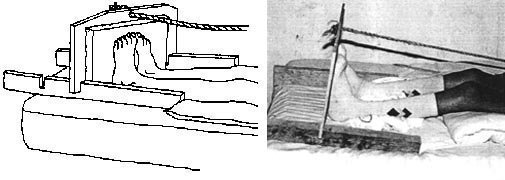

The solution: a flexible foot-board pulled by a rope.

Materials: a short piece of thin wood plank; 2 narrow

boards about 2 cm. by 6 cm. by 60 cm. long; a piece of rope (about 1

meter); a piece of dense rubber foam (to cushion the feet).

Construction: Notch wood, drill hole, and assemble as

shown.

How it works: The footboard is placed

to keep the feet upright (as near to 90 degrees as possible). For

his heel-cord stretching exercises, Osvaldo pulled the rope himself.

As Osvaldo pulls the rope, the front ends of the side boards sink

into the foam mattress, angling the footboard forward and stretching

the feet (and heel-cords).

Results: The device worked fairly well.

The hinge-like action, which allowed the foofboard to angle forward

more when pulled, was unplanned and recognized only when tried. The

device actively involved Osvaldo in exercises to correct and prevent

further contractures of his ankles. Moreover, to do the exercises,

he had to move his upper body and shoulders somewhat, which he had

resisted doing because of his hypersensitive right arm. So the foot

exercises were also good therapy for his painful shoulder and arm. |

| 245

|

AN ADJUSTABLE BED TABLE

The problem: Osvaldo, who before his

accident had been right-handed, needed to develop confidence and

skill in using his left hand. He also needed activities to keep him

interested and busy during the long periods of lying in a flat or

semi-sitting position. For this, he needed a table which could

easily be rolled over his bed, and which could adjust both in slant

and in height. The group decided that a wooden design, which any

village carpenter could make, would be ideal.

Solution: Two of the workers in the

carpentry shop (Mario, who is paraplegic, and Rafa, who is

quadriplegic) designed and built the wooden table shown below.

| Small bolts with butterfly nuts for adjusting height. |

| Table pivots on bolt passing through curved groove. |

| Butterfly nuts for adjusting angle. |

| Wooden wheels allow bed table to be easily rolled into place,

yet provide enough friction for stability. |

| Wooden bar keeps objects from slipping when table is tilted.

The bar is attached with wooden rods (dowels) and can be removed

when table is flat - for eating, etc. |

Results: The table was handsome,

strong, and it worked well. It was large and solid enough to double

as a drafting table. It could also be used as a typing or work table

by someone in a wheelchair. This model can be easily made or adapted

by a local carpenter. Wooden wheels help keep the cost down. The

only welding necessary was to fasten the "wings" on the butterfly

nuts. (Ordinary nuts and bolts would work as well, but require a

wrench.) For transport, the wing nuts can be removed and the whole

table packed flat.

The adjustable bed table made it easier for Osvaldo to do many

activities in bed. He took particular pleasure in drawing. He began

to confront the challenge of learning to draw and write with his

left hand.

Games. Some of the school children who came to

visit Osvaldo made a checker board for him. While

playing such games with other children, often the sign of a smile

would creep over Osvaldo's face.

The main disadvantage of the table was its heavy weight and bulky

size (as compared to the welded commercial hospital bed-tables that

roll in from one side of the bed).

|

| 246 |

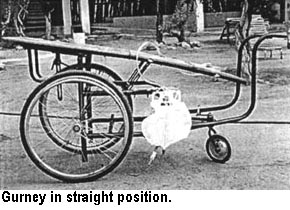

GURNEY (NARROW WHEELED BED) WITH ONE-HAND DRIVE

Problem: To heal his pressure sores,

Osvaldo needed to lie face-down for long periods. However, his

paralyzed right arm was stiffly contracted over his chest. The arm

was so hyper-sensitive that it would take a long time with therapy

to regain enough flexibility to place it out of the way so that he

could lie face down.

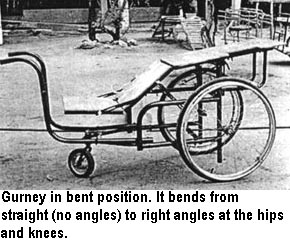

Another problem was how to help Osvaldo

regain flexibility (bending ability) of his hips and knees while

lying face down. A special gurney could be built for him with

adjustable angles at the hips and knees. Actively moving about on

the gurney would also stimulate circulation and thereby speed

healing of the pressure sores.

But the biggest problem was: How could

Osvaldo wheel and steer a gurney with one hand?

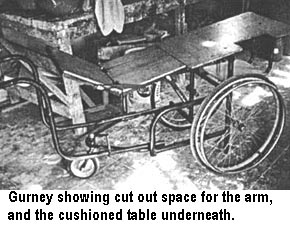

Solution: A one-hand-drive gurney with

adjustable hip and knee angles, and with a cut-out section and

lower-level table for his paralyzed arm.

A rectangle was cut out of the bed of the gurney at the level of

Osvaldo's right shoulder, so his stiff arm could rest on a small,

cushioned table underneath.

|

| 247

|

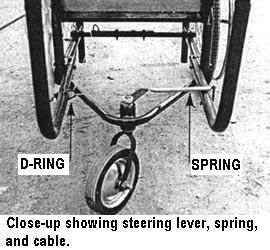

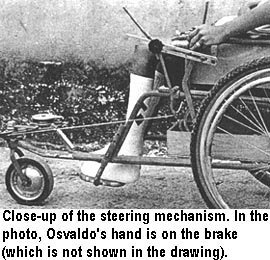

The steering device for the one-arm-drive gurney

| A sliding knob is attached by a pivoting bar to a wire cable. |

| The knob slides up and down to change the angle of the rear

wheel. It screws down tightly to hold the rear wheel in the

desired position. |

| The cable, which passes through a series of D-rings, controls

the angle of a single, small rear caster wheel. |

| A lever arm, attached to the vertical post of the caster

wheel, is pulled in one direction by the cable, and in the other

direction by a spring. |

To move straight ahead, Osvaldo tightens the

steering knob to hold the rear wheel straight, and rolls the gurney

by pushing the hand rim of the left big wheel. To make a

turn, he quickly loosens the knob, slides it up or down to

angle the caster wheel either to the left or right, and again locks

the knob in place. The turn completed, he again moves the knob and

locks it in the straight-forward position.

Results: Although it had certain

problems and limitations, the gurney was a great success for

Osvaldo. Through repeated experimentation, and a flood of complaints

and suggestions by Osvaldo, the steering mechanism was gradually

improved.

At first, too much force was required to make a right turn, and

only a very wide turn was possible. But, by placing the D-ring

(pulley) nearest the caster further back to provide a pull at closer

to 90 degrees, sharper turns could be made, and made more easily.

Also, at Osvaldo's insistence, a rack was added on the front of the

gurney to hold a large bottle of water (see

page 197). This request by Osvaldo

reflected his growing interest in making sure he drank enough

liquids to avoid further urinary infections. |

| 248

|

| At first it was very difficult to

place Osvaldo on the gurney and to position his hyper-sensitive arm

without hurting him. But after a few days, the arm began to get a

little more limber and the boy learned to help position both himself

and his arm. Once in position, he was soon able to stay comfortably

on the gurney for hours. As the angles of the gurney at Osvaldo's

hips and knees were gradually increased, the flexibility of his

joints improved rapidly. Osvaldo soon began to spend much of the

time on the gurney with his hips fairly straight and his knees bent

up. The elevated position of his feet helped to prevent them from

swelling. This, in turn, helped his ankle sores to heal.

In summary:

| The gurney contributed to Osvaldo's rehabilitation

in a wide variety of ways:

| It helped to heal his sores by removing the pressure on

them (by his lying face down). Also, his energetic activity

on the gurney improved his circulation, which helped the

sores to heal faster. |

| It protected his hypersensitive right hand by supporting

it on a pillow below his body. But at the same time, his

activity on the gurney caused some movement of his delicate

arm and hand. He tolerated this because his mind was on

other things and he was having a good time. Gradually his

hand became less sensitive, so that he cautiously began to

move it, to wash it himself, and to gently do exercises to

get back flexibility. (Although the hand remained paralyzed,

some strength returned in his shoulder, and eventually he

started using it as a helping hand.) |

| The hinged bed of the gurney helped to correct the

extension contractures of his hips and knees, by gradually

increasing the bend of its jointed sections. |

| With its one-arm drive, the gurney allowed him the

freedom of self-controlled and self-powered mobility. This

greatly improved his outlook on life and on himself. |

| Elevating his feet by flexing the hinge at his knees

improved the circulation and decreased the swelling of his

feet. (This speeded the healing of the deep sores on his

ankles.) |

| By encouraging physical activity and more drinking of

water, the gurney helped to prevent urinary infection and

kidney stones. |

| Wheeling himself around on the gurney helped to

strengthen his more useful arm, providing therapy that was

both functional and fun. |

| Altogether, the gurney gave him new self-confidence and

improved his state of mind. His greater happiness was due

partly to being able to go where he liked under his own

power, and partly to his participation in designing and

improving his own equipment. |

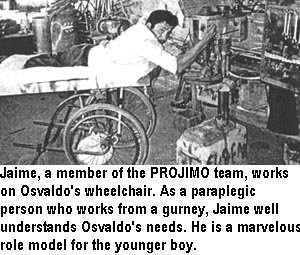

| The role model of other disabled persons who ride and

work on gurneys helped a lot. |

|

|

| 249

|

A ONE-ARM-DRIVE WHEELCHAIR

Once Osvaldo's pressure sores had healed and he regained enough

flexibility so that he could sit, he needed a one-hand-drive

wheelchair.

The problem: Hemiplegic (one-hand

drive) wheelchairs are manufactured commercially in the United

States and in other rich countries. But they are very expensive and

are usually not available in poor countries. Also, the drive

mechanism is relatively complex and tends to break down quickly on

rough terrain. (The problems with these commercial one-arm-drive

wheelchairs are further discussed in

Chapter 39.)

Occasionally, PROJIMO has a second-hand hemiplegic wheelchair

donated from the cooperating hospitals and programs in the United

States. But at the time Osvaldo needed one, none was available.

Solution: Like many rehabilitation

programs in the Third World, PROJIMO has a big need for an

easy-to-build, low-cost, hemiplegic wheelchair. It occurred to the

workers in the shop that the same front-wheel steering mechanism

used for Osvaldo's gurney might work for a wheelchair.

Through a lot of trials and suggestions by Osvaldo, a design was

created.

A single front caster was controlled by pulleys and cable to a

steering knob mounted on a vertical bracket on the left side of the

chair.

Trial construction, trouble-shooting, and improvements.

In the early design, the very small D-rings (improvised front

pulleys) gave too much resistance and made steering difficult.

In the modified design, larger, smoother-running pulleys were

used. This made steering easier.

Pulling on the lock-knob required too much force for Osvaldo

(whose back was still painful). Therefore a longer lever-arm was

added. |

| 250

|

Design details of Osvaldo's wheelchalr:

Results:

After several modifications to make steering easier, Osvaldo

found the chair very useful. He learned to steer it with remarkable

agility and became relatively independent. The strength in his left

arm increased. The removable arm rest on the right side, plus the

easy access for his feet, made putting him in and out of the chair

relatively simple. He soon learned to help with the transfers, using

his left arm.

One disadvantage of this design is its lengthy forward extension

to support the steering wheel. This makes moving about in close

quarters more difficult (although far less so than the

front-wheel-drive tricycles with a bicycle wheel at the front, which

are even longer and more cumbersome). On the positive side, the

narrowness of the "nose" of Osvaldo's chair, and the small front

wheel, make moving about in close quarters somewhat easier.

In conclusion, the Osvaldo one-hand-drive wheelchair provided a

relatively low-cost, easily constructed option in situations where

standard hemiplegic chairs are seldom available, too costly, and not

durable. Although to our knowledge this new wheelchair has not yet

been duplicated, we feel it has the potential to help fill the

enormous unmet need of hemiplegic wheelchair riders in low-income

situations. However, the design still needs to be simplified and

improved. One possibility might be to shorten the forward extension

to make it easier to move about indoors.

For another, better design of a one-arm

wheelchair, see the next chapter (page

253). |

| 251

|

Summary of the Combined Methods of Managing Osvaldo's

Pressure Sores

Following his accident Osvaldo lay on his back for 5 months

without being turned. When he came to PROJIMO he had 11 pressure

sores, extending from mid back to his heels. The largest sores were

2 to 3 inches across. Most were fairly shallow (bone not exposed)

and his mother had kept them fairly clean. However, there was some

dead as well as unhealthy gray tissue on the surface of the sores.

The deepest sore, about 2 inches long, was over the heel cord

(Achilles tendon) of his left foot; the tendon was exposed.

Complicating treatment of Osvaldo's pressure sores was his

hypersensitive paralyzed right arm, which had become rigidly

contracted over his chest. This stiff, painful arm prevented him

from lying either face down, or on his right side.

SIX STEPS TAKEN TO PROMOTE HEALING OF OSVALDO'S

PRESSURE SORES:

|

| 1. Minimize pressure over the sores while

lying down. This was done by:

| Putting cushions under his legs to take pressure

off his buttocks, lower back, and ankles/heels. |

| Providing a ring so he could lift himself up. |

| Using a thick sponge mattress. |

|

2. Adequate cleaning of the sores; treatment

with sugar and honey.

|

3. Wheeled mobility while lying face down,

with the feet up (until the sores heal).

4. Lots of activity to speed up circulation,

which causes faster healing.

|

5. Food rich in calories, protein, and iron

to strengthen the body and blood, to speed healing.

|

6. Management of the boy's overall health,

especially his urinary system.

|

7. Strengthening the good arm and increasing

his ability to change his position.

|

8. Encourage the boy's understanding and

responsibility in healing and preventing pressure sores:

above all, changing position and lifting up the body

often. |

|

|

| 252

|

MEDICAL TREATMENT OF OSVALDO'S PRESSURE SORES

Treatment involved daily washings, at first

brisk enough to remove dead flesh. Once the healthy red flesh was

exposed, cleansing became quite gentle so as to avoid damage to the

newly forming tissues. After cleaning the sores, a paste of

bees' honey mixed with sugar was applied to the sores and

covered lightly with gauze (see page 156).

Results: With this treatment program,

combined with the management techniques reviewed on

page 251, the sores healed remarkably fast. Even the deep sore

over Osvaldo's heel healed in 3 weeks. The team feels it was the

combined actions of treatment and management that led to rapid

healing. Surely the change in Osvaldo's attitude made a big

difference. He began to oversee and take responsibility for his own

care, advising his mother and other attendants about how to place

padding to relieve pressure over bony areas, and asking to be turned

or moved after a time in one position. His increased physical

activity also probably contributed to his quick healing, as did the

many hours he spent each day lying face-down on his specially

designed gurney.

| Comparison of PROJIMO's methods with hospital

treatment of Osvaldo's pressure sores. The steel

rods surgically placed in Osvaldo's back after his accident came

loose, and had begun to poke through the skin. To remove the

rods, Osvaldo was taken to an orthopedic hospital in California.

During the 2-day drive, a new small pressure sore formed over

his sacrum (bottom part of the spine). In the hospital,

Duoderm (a costly, medicated, absorbent bandage) was put

over the sore, and Osvaldo was placed in bed for 24 hours a day.

He lay on his back on a special air-flow mattress run by an

electric air-pump, so that the pressure over each small area of

the body was constantly changing. In the hospital, with all

this costly treatment and equipment, the boy in his space-age

bed was deprived of all choice or responsibility for his own

care. His pressure sore - smaller and more superficial than ones

that had healed in 3 weeks at PROJIMO - took over 2 months to

heal.

Ironically, from lying flat on his back for so long in the

hospital, Osvaldo's knees and hips were again becoming rigid. A

physiotherapist, attempting to restore flexibility, used too

much force and broke his right leg. With his leg in a cast for

weeks, a new deep pressure sore formed on his right heel. Again,

it took over 2 months to heal. During all these months in the

hospital, Osvaldo's anger, hostility, and depression - which he

had gradually been overcoming - re-emerged. The nurses were at a

loss for knowing how to get him to cooperate. |

COMPARISON OF HEALING TIME OF SIMILAR PRESSURE SORES ON

OSVALDO'S BACKSIDE

|

Comparing results of Osvaldo's management at PROJIMO with those

at this modern orthopedic hospital, it appears that the

comprehensive, action-oriented, whole-person approach used

at the village center was relatively successful - at least for the

healing rate of pressure sores. The rapid healing, achieved with

Osvaldo's sores has occurred with many (but not all) persons

attended at PROJIMO. More comparative study is needed.

|

|