| 207

|

CHAPTER 32

Mobility Aids, a Walking Toilet,

and a Seeing-Eye Person for Carlos

CARLOS is the son of migrant farm workers from

Oaxaca, one of the poorest states of Mexico. During harvesting season, his

family used to come north to Sinaloa (the state where PROJIMO is located)

to pick tomatoes. When he was 8 years old, Carlos already worked with his

parents in the fields. Sadly when he was 10, the boy was hit by a truck

and his brain was severely damaged. He remained mentally and physically

disabled, and also visually impaired.

Months after his accident, Carlos was taken to PROJIMO by state

social workers. While he was still in the hospital, his parents had

abandoned him. Apparently they had gone back to Oaxaca, without leaving an

address. The social workers asked if PROJIMO could provide rehabilitation

for the boy. In effect, PROJIMO became Carlos' new family.

On arrival, Carlos already had secondary physical and emotional

problems. His spastic body had become very stiff, and he had contractures

of his hips and knees. He was almost totally blind, and his mind did not

function well. He had very little short-term memory and difficulty

learning even simple things. The few words he spoke were mostly abusive

swear words. He got angry easily, and often cursed and spit at persons

trying to help him. He would repeatedly plead "I want water!" or "I want

food!" even when he had just had plenty to eat and drink. He constantly

wet and pooped his clothing and bed.

Carlitos (as he was affectionately called) needed a lot of personal

assistance, plus a huge amount of understanding and patience. Fortunately,

an older woman named Rosa, who has worked at PROJIMO for years, became

like a mother to him. Rosa lovingly bathed him and washed his soiled

clothes 2 or 3 times a day.

Mobility. To help Carlitos move himself about, one of

the first things the shop-workers did was to build a wheelchair adapted to

his size and needs. At first he could not move his wheelchair at all. But,

little by little, he learned to roll it about. In time, he could more or

less find his way on the pathways between buildings.

Water Play as Therapy. In preparation for standing and

walking, the team helped Carlitos with range-of-motion and stretching

exercises. These helped to correct contractures and reduce the spasticity

of his hips and knees. At first, he angrily resisted the exercises. But

when the team tried working - and playing - with him in water, he loved

it. The water supported his weight and let him move without the fear of

falling. His pleasure and activity in the water seemed to help his stiff

body to loosen up.

|

| 208

|

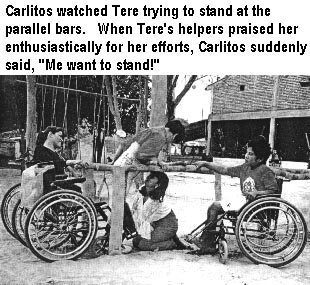

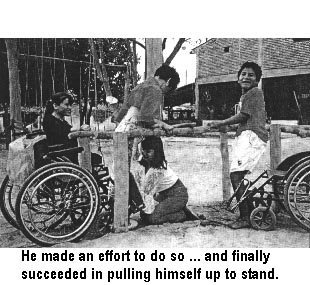

| Standing. Although

Carlitos' knees still bent stiffly when he tried to stand, the team felt

he had the potential for learning how to stand and walk. At first he was

non-cooperative, and understandably so. After nearly a year without

weight-bearing, standing hurt his feet. But with daily practice his feet

toughened. The team found that the best way to get Carlos to try to

stand was to put him with another child who was learning to stand.

|

| 209

|

Walking.

When Carlitos first tried to stand at the parallel bars he had very poor

balance. He practiced daily. Little by little, his balance improved

until he could take a few steps, holding onto the bars. Walking.

When Carlitos first tried to stand at the parallel bars he had very poor

balance. He practiced daily. Little by little, his balance improved

until he could take a few steps, holding onto the bars. After months

of practice, he learned to walk back and forth between the bars with

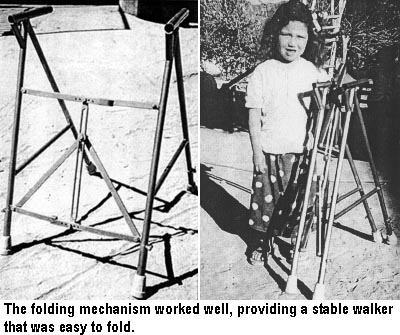

fair stability. When Carlos began to say "I want walker!" the team asked

Jaime to design a walker that would meet the boy's needs.

Mari and Inez tested him with walkers of different sizes and heights.

At last they found a combination of features that allowed him to stand

straighter and more firmly. Jaime, a paraplegic wheelchair builder who

works lying on a gurney (wheeled cot), built the walker out of steel

tubing. He used thin-wall electric conduit tubing, the same material

used to make the wheelchairs.

|

To make the folding mechanism, Jaime used the same recent

innovation that the shop workers use on an improved design of the

Whirlwind wheelchair (see p.190). |

|

|

| 210

|

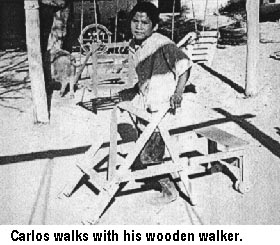

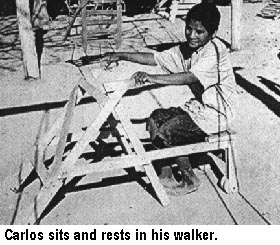

A Wooden Walker with a Seat

Carlitos enjoyed walking with his new metal walker. But his attention

span was brief and he tired quickly. After a few minutes, he would want

to sit in his wheelchair. And a few minutes later, he would want to walk

again. Because he was blind and had difficulty remembering, it was hard

for him to find things. All day long he would call out to people to

bring him his walker or his wheelchair. When everyone was busy there was

sometimes a delay, and he would get angry and frustrated. "Carlos want

walk NOW!" he would wail.

One day, Juán, a disabled carpenter and brace-maker, asked Carlos, "Carlitos,

would you like a walker with a seat on it, so that you can sit down and

rest when you're tired of walking?"

"Yes" said Carlos eagerly. "Carlos want walker with seat." So Juán

made him a unique wooden walker with a seat.

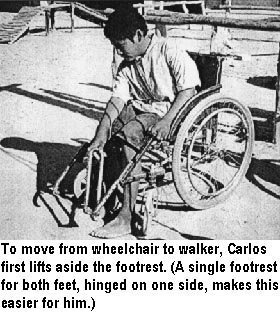

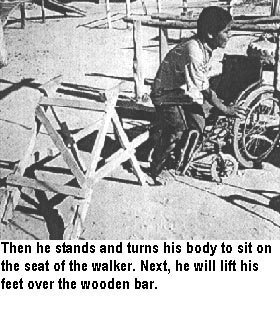

Although transferring from his wheelchair to the wooden walker

required stepping over the wooden bar that supported the seat, Carlos

soon learned to transfer without help.

With his new walker, Carlos became more independent. He no longer

needed to always ask people for help, and he began to take pride in

doing things for himself. His self-help skills in walking helped prepare

him for a better response to toilet training (see p.212). |

| 211

|

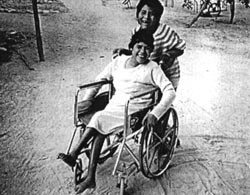

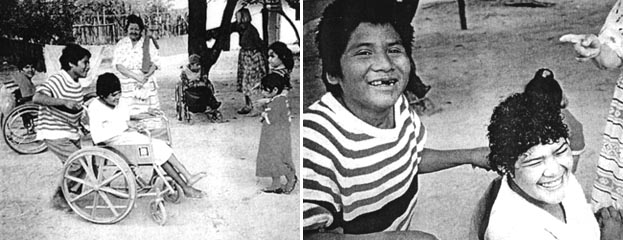

| A "Seeing-Eye Person" for Carlos.

With his walkers, Carlos' walking improved. But being blind, he had a

hard time finding his way. Someone suggested a seeing-eye dog. But it

was easier to provide a "seeing-eye person."

At PROJIMO there are always young wheelchair users who have trouble

moving about by themselves. These include Tere and Lupita, who have

spastic arms and legs. One day, Tere was practicing standing at the

parallel bars. At the same time, Carlos was walking in circles around

the outside of the bars, holding on with only one hand. To do this,

Carlos had to circle around Tere's wheelchair. Once when he took hold of

the handles of her wheelchair, he laughed and tried to push it, like a

walker. That gave Rosa an idea.

A Wheelchair as a Walker. When Tere finished her

standing session at the bars, she said she wanted to go to the laundry

area to wash her clothes. Because she has difficulty moving her

wheelchair on the uneven ground, she asked Rosa to push her.

Half-joking, she said, "Carlitos, why don't you push Tere to the laundry

area?"

Carlos grinned with excitement. "Yes! Carlitos want push Teresita!"

At first Tere was reluctant. Although she and Carlos were friends,

she feared he would wheel her into a pit or tree. But Rosa explained to

Tere that, by letting Carlos push her, she would be helping him with his

therapy, his independence, and his self-esteem. So Tere agreed to give

it a try.

Rosa guided Carlos' hands to the handles of Tere's wheelchair. Carlos

pushed it eagerly. To keep on course, Tere told the blind boy where to

go. At first he was confused. But after a while he learned to tell

"Left!" from "Right!" and steer accordingly. Carlos had never seemed so

happy, nor Tere more scared.

Carlos as a wheelchair-rider's attendant.

By that afternoon, Carlitos proudly also began to help Lupita move

from one area of the playground to the other. He was walking more and

better than he had ever walked before. And he was able to find his way,

thanks to his "seeing eye persons." This mutual self-help by persons

with different disabilities helped to build self-confidence in all who

were involved, Carlos took great pride in his new role as a "wheelchair

attendant."

Peer therapy. Tere, likewise, took pleasure in

knowing that she was helping Carlos both develop his walking skills and

gain a sense of being useful and appreciated. Lupita, whose mental

handicap is as great as that of Carlos, was all smiles with the

enthusiastic services of her newly found driver. In this way, multiply

disabled young people have learned to help one another. |

| 212

|

Toilet Training as Preparation for Standing, Balance, and Manual

Skills

Carlos' toilet training advanced slowly, with modest gains. At first,

he always pooped in his cot at night. Then he began occasionally to

crawl off his cot and poop on the floor. To reinforce this response and

take it further, Juán - with the help of two village school children -

made a simple wooden toilet seat that could be placed over a bucket next

to Carlos' cot.

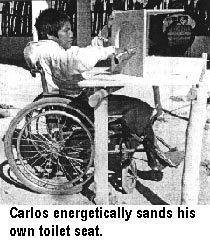

To involve Carlos more with making his toilet, the

group asked him if he wanted to help sand the wooden seat. Carlos,

always eager to "work," responded, "Yes, Carlos want sand toilet."

Perhaps because he had already tried sitting on the toilet and

identified it as his, he did the sanding with more energy and

persistence than usual.

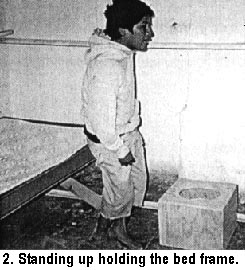

The next step was practice using his toilet. This

involved sitting on the edge of the bed, standing up (while holding a

metal bed frame turned on its side at the head of the bed), unbuttoning

and loosening his pants, lowering his pants enough to avoid soiling them

(while leaning against the bed frame), and sitting on the toilet. After

using the toilet, he learned to repeat the same steps in reverse.

Steps in Carlos' toileting practice:

Carlitos still has a long way to go until he has no accidents in his

bed. But his bedside potty not only helps him with toilet training, it

also helps with standing, balance, dressing and undressing skills, body

coordination, and manual dexterity. He is eager to learn new skills, and

takes pride in having helped make the toilet he is learning to use. |

| 213

|

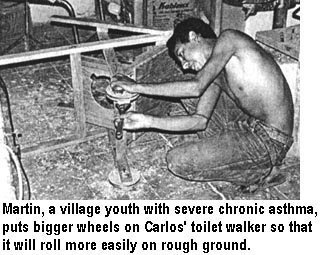

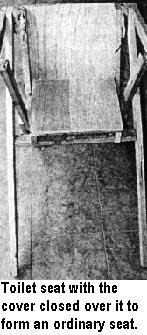

A WALKING TOILET FOR CARLOS

Problem. Carlos' new

walker-with-a-seat (described on page 210)

allowed him to sit down when and where he wanted. But the design had one

big problem. Because the seat was mounted behind the space where he

stood to push the walker, the whole device was over a meter long. This

made moving in close quarters very cumbersome. If Carlos was to learn to

walk to the dining room, he needed a walker that was more compact.

To

solve this problem, PROJIMO designed a compact walker with the

seat in front of him, not behind. Although he had to turn around to sit

down, this walker had the advantage that it had no poles to step

over. To

solve this problem, PROJIMO designed a compact walker with the

seat in front of him, not behind. Although he had to turn around to sit

down, this walker had the advantage that it had no poles to step

over.

Also, it simplified transfers from the wheelchair. Carlos

could wheel his wheelchair between the rear legs of the walker, take

hold of the walker's handle-bars and easily stand up.

Adaptation for urinating. One complication to having

the seat of his walker in front of him was hygiene. Now that Carlos was

partly toilet-trained, to urinate he would simply stand up and lower his

pants. With his old walker (with the seat behind) that was all right.

But to avoid wetting the forward-positioned seat of the new walker, the

seat needed to be hinged so that Carlos could lift it out of the way

before urinating.

|

| 214

|

Adding a potty. The idea to adapt the walker as a

portable toilet came from necessity. It was springtime. The plum trees

at PROJIMO hung heavy with fruit. The ripest plums fell to the ground.

Carlos would park his walker in the shade of the trees, sit on the seat,

and lean over to feel with his hands for the fallen fruit. In a short

time, he would stuff his belly to bursting.

But this feast had a nasty side effect: diarrhea. Because

Carlitos was blind and forgetful, he had not learned to take himself to

the outhouse. Sometimes, when he had to go in a hurry, he called someone

to take him. And sometimes he would poop in his pants. Rosa, who had to

bath him and wash his clothes, was at her wits end.

To solve this problem, Polo helped to convert Carlos' walker into

a mobile toilet. He cut a hole in the seat to hold a

plastic bowl. Supported by its rim, the bowl could be lifted out to

empty it. To use as an ordinary seat, a square board, hinged at the

back, could be lowered over the bowl. To urinate, Carlos could swing the

whole toilet up out of the way.

The invention saved the day. From one day to the next, Carlos became

more independent in his toileting. The stimulation caused by his

high-plum diet gave him plenty of practice, and he quickly learned to

lift the lid and lower his pants.

What

he never learned to do was to empty his potty. We all learned - the hard

way - about the need to empty Carlos' potty often enough, especially

during plum season. What

he never learned to do was to empty his potty. We all learned - the hard

way - about the need to empty Carlos' potty often enough, especially

during plum season.

One day, when he had filled his potty to the brim, he lost his

bearings and fell over with his walker. He and the walker were covered

with the potty's rank contents. Cecilia and the author helped with the

clean up. It was no fun!

But, despite the occasional mishaps, Carlos loved his new walker. It

not only gave him new freedom to move about, but helped him become more

fully self-sufficient with his toilet. |

| 215

|

Improvement

Bit by bit, in the 3 years that Carlos has been at PROJIMO, both his

physical and mental abilities have improved. He has remembered songs

from early childhood, and has learned new ones. He now talks more

cleverly, remembers people's names, gets angry less often, and laughs

gladly in response to friendliness or assistance. His common phrases now

include "I want to walk" and "I want to work." He takes pride in using

his toilet, and in staying dry and clean (sometimes).

His attention span is still brief, but for several moments at a time,

he helps with activities in the toy shop. All in all - through a team

effort in which disabled persons help each other - Carlos has come a

long way.

Most important of all, Carlos has made friends and learned how to

enjoy life and people.

In addition to better balance, he now has more self-confidence in his

abilities. It was a day for celebration when, at last, Carlos

began to stand without any support or assistance. |

|