| 137

|

CHAPTER 23

Helping José Walk

and Talk after His Stroke

JOSÉ, who is 48 years old, was brought to PROJIMO by

his concerned wife and son. Six months before, he had had a stroke (cerebral

vascular accident) that paralyzed his right side. At first he could not walk

or talk. Weeks later he began to walk with much difficulty, using a cane.

But his speech did not return. He had trouble expressing his wishes. He got

angry with his wife when she did not understand him - and she would get

angry with him. She thought his inability to speak came from weakness of his

mouth, and that if he could learn to move his lips and tongue better he

would be able to talk. She was sure he understood everything she said to

him, and was irritated that at times he didn't respond appropriately.

Fortunately, when José first visited PROJIMO, Ann Hallum, a visiting

physical therapist, was there facilitating a course to help up-grade the

village team's knowledge and skills.

CAUSES OF LANGUAGE PROBLEMS. Ann explained that, after a

stroke, difficulty with speech and communication can be caused by a

combination of problems, depending on the area of the brain that was injured

(by stroke, illness or injury), Injury to one area of the brain's "language

center" can prevent the person from understanding the spoken or written word

(receptive aphasia). Damage in another language area can prevent

her from recalling or forming words or phrases correctly, either in spoken

or written form (expressive aphasia). Persons with severe language

problems may have losses both in receiving and in expressing language (total

aphasia).

José's right-sided paralysis meant that his left brain (with the

"language center") was damaged. Simple testing was needed to find out the

causes of his difficulties with communication.

TESTING JOSÉ'S UNDERSTANDING OF LANGUAGE. To test how

well José could associate words with the things they represent, a PROJIMO

worker, Andrés, put a number of objects - a carrot, a spoon, a tomato and a

cup - in front of him. Andrés said, "Give me the carrot." José looked at the

different objects a long time, then picked up the carrot. Everyone clapped

and praised him. However, with the other objects he had more difficulty, and

often made mistakes. When Andrés said, "Give me the tomato," José pondered a

long time, then handed him the spoon.

Further testing showed that although José had a lot of trouble with nouns

(things), he was much better with verbs (action words). Often he would

understand a noun when it was used in a phrase involving a familiar action.

For example, when Andres asked him to pick his sombrero (hat) from several

objects on the table, he was confused. But when Andres said, "Take off your

sombrero," José gave a sigh of understanding and at once took off his hat.

These findings gave clues to how his family might communicate

more effectively with José. It helped his wife understand why he

often did not respond appropriately to her questions; why he would grunt

"Yes!" when she asked, "Do you want a cup of coffee?" and then get upset and

frustrated when she brought him coffee. |

| 138

|

| Sometimes, when José wanted to say

something, he would repeat the word "Burro!" (donkey) many times. This

used to make his wife angry. But when, during the testing, she saw his

confusion with names of things, she gained more understanding of his

problem. During the testing, it became clear that José

had difficulty with names of things. But when his mistakes were clearly

pointed out, he learned fairly quickly. When he was asked to pick up the

spoon, but took the tomato, Andrés would say to him, "No, that is not a

spoon, It is a tomato." After 2 or 3 repeats, José would usually pick up

the spoon when asked.

Helping José to Talk

A PICTURE BOARD FOR BETTER COMMUNICATION. Because one

of José's biggest difficulties with language was recognizing the names of

things, Andrés and others sat down with José and his wife and drew up a

list of the things that were most important for communication in the home.

This included a variety of foods and other objects.

They drew pictures of these things on sheets of paper. To make it easier,

they started by drawing a single object on a sheet, and showed José one

drawing at a time. They asked him to point to the thing he wanted to have

or to say at that moment.

After practice with this, the team made communication boards

for different groups of things. One of the first boards they made was of

foods.

When considering which foods to include, Mari's daughter, Lluvia,

insisted that a drawing of ice cream be included. Mari thought

ice cream would not be one of José's priorities. "But what if he wants

it?" Lluvia insisted. So, ice cream was included.

When he began using the list, one of the first things José pointed to

was ICE CREAM. When it was brought to him, he laughed with delight.

With practice, José learned to identity most of the objects on the boards

and to recognize their names when spoken. He learned to use the board to

point to something he wanted, especially when he had trouble associating

it with the right word.

Later, to make it easier for him to carry his sheets of pictures, the

team reduced and reassembled the most useful drawings into a small

notebook that he could carry in his pooket.

During the days that José was at PROJIMO, his wife and Andrés used both

the picture boards and real objects to help him associate words with

things and actions. Although progress was slow, his communication skills

improved. Most important, perhaps, was that José and his wife were less

frustrated with one another and began to realize that they were both doing

their best. |

| 139

|

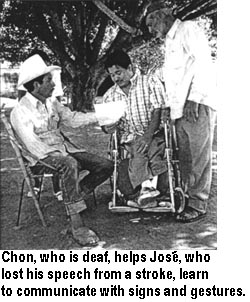

A DEAF MAN HELPS JOSÉ COMMUNICATE WITH SIGNS

In helping José to re-learn to recognize words, it became clear that he

was quick to notice and interpret gestures and signs.

One day a deaf carpenter named Chon, who sometimes helps at PROJIMO,

saw Andrés teaching José with the picture board. Quickly understanding

José's difficulties with words, Chon began to explain things to José,

using signs and gestures. (Chon's sign language was not a standardized

formal system. It had been developed out of necessity, by him, his family,

and the villagers since he was a child. But Chon managed to communicate

and understand almost everything with remarkable clarity.) José picked up

on Chon's signs very quickly. This gave José's wife new ideas for

communicating with her husband. Everyone thanked Chon for his valuable

assistance, and he was delighted to have been able to help with his

expertise.

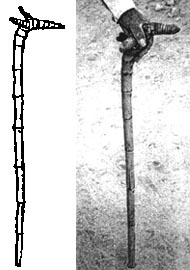

Helping José Learn to Walk Better

When José first came to PROJIMO, he walked with difficulty, using a

home-made cane made from a bamboo-like plant called otate. The

curved top of the cane was formed by the main root of the plant. Two

smaller side-roots provided additional supports for a firm grip.

For several weeks after his stroke, José's right leg was almost completely

paralyzed. Then, little by little, it began to recover strength. José

learned to walk again by bending the weak right knee slightly backward, in

a locked position that supported his weight without using his weak thigh

muscles.

This back-kneed gait caused him to walk awkwardly with short shuffling

steps, and with danger of falling hard if he lost his balance. (After his

stroke, José's balance was poor. Walking with his knee locked backward

made his balance and stability worse.)

|

| 140

|

Improvement with Time. On testing José at PROJIMO 8

months after his stroke, the team found he had regained much of the

strength in his weak leg. He was able to partially squat on that leg

alone. With daily squatting exercises, the leg would probably get stronger

still.

Problem. José's right leg was now strong enough to let

him walk fairly normally. But the habit of locking his knee backward at

the start of each step was, by now, strongly fixed. Inez, a physical

therapy assistant at PROJIMO, encouraged him to bend his right knee while

walking. He had José practice shifting weight from one bent knee to the

other while he held onto a bar. Once José understood the request, he did

this willingly. But he still walked with a "back-knee." What to do?

A Partial Solution. Something was needed to help José

break his habit of back-kneeing and to relearn to bend his knee when

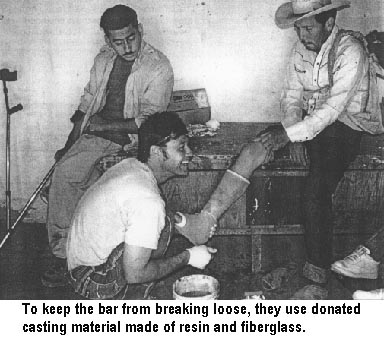

stepping with his leg. The team decided to experiment with a

leg-brace that would push his knee forward when he put weight on his foot.

Before making the plastic brace, Inez did a trial with a

plaster cast. The cast lifted the front of the foot slightly

upwards, so that when the foot was flat on the ground, the knee would

bend. However, this was not enough to prevent José from walking with his

knee pushed back (on his heel with his toes in the air). Therefore, Inez

mounted a metal bar in the cast under José's foot. The bar projected

backwards, behind the heel. This way, when José took a step with his right

foot, the heel bar would push the foot to make it land flat on the ground.

This would cause the knee to bend forward with each step.

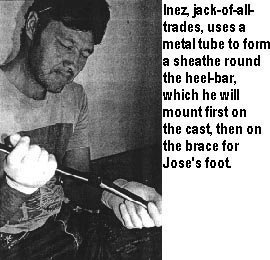

To make the heel bar removable and adjustable, Inez

inserted a flat iron bar into a thin-walled metal tube. He then hammered

the tube into a rectangular shape around the flat bar.

The experimental cast worked fairly well. Although José felt awkward in

it, he at once began to walk bending his knee, and soon he had a more

normal gait. The cast had the additional advantage of correcting the

foot-drop (front of the foot hangs down when the foot is lifted) which

remained after his stroke... Within an hour or so of practice, José put

aside his cane and began to walk with larger, more even steps. He was

delighted, although still somewhat disturbed by the cast. |

| 141

|

Casting José's Leg

|

| 142

|

A plastic brace with an adjustable heel bar.

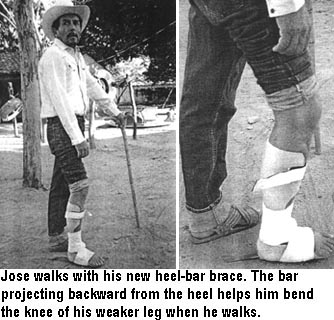

After demonstrating that the cast with the heel-bar helped José bend

his knee while walking, Marcelo made a plastic brace in which he mounted

the same bar. Because the experimental cast had bent José's knee forward

only slightly - and sometimes the knee started to bend backward - when

making the brace, Marcelo increased the ankle-angle so that the front of

the foot was somewhat higher.

José practiced with his new brace at PROJIMO for a few more days before

he and his wife went home. It is still too early to know the final

results. For the time being, José walks more evenly and with larger, more

regular steps. The team hopes that after a few weeks (or months?) with the

brace, José will become so accustomed to bending his knee when he walks,

that he will continue to bend it when he no longer wears the brace.

Adjustrnents. At the time of this writing, José had returned home

with his brace. As he gets used to walking with his knee bent, the

heel-bar can gradually be pushed deeper into the brace to make it shorter.

Depending on his progress, José may soon be able to stop using the bar

brace. For a while, he may need a modified shoe with the heel that sticks

2 or 3 centimeters out behind. This, too, will push his knee forward

gently, though less powerfully than does the long heel bar. |

|