CHAPTER 50

Organization, Management, and Financing of a Village Rehabilitation Program

ORGANIZATION AND MANAGEMENT-

A 'PEOPLE-CENTERED'APPROACH

In Chapter 45 we spoke of top-down and bottom-up approaches to a community program. Programs that are 'bottom-up', or begun by disabled persons, family members, and concerned members of the community, tend to be organized and managed very differently than top-down programs.

A sense of equality among all persons taking part in or benefiting from the program is basic to the organization of bottom-up or 'people-centered' programs:

| Everyone is considered equal | |

| Leaders are coordinators, not bosses. | |

| Decisions are either made by the group or can be openly challenged by the group or by any of its members. | |

| Everyone has the same rights and deserves the same respect. The ideas and opinions of a disabled child or her parents are just as important as those of the village rehabilitation worker or visiting professional. All are equal and valuable members of the rehabilitation team. |

In a people-centered program, goodwill, friendliness, and a feeling of shared pleasure in meeting each other's needs are often given more importance than polished floors, arriving on time, exact records, number of hours worked, or how many wheelchairs are produced by each worker each month. Success of the program is measured not so much by formal evaluation as by the 'smile factor': how good everyone-workers, parents, and children-feels about what they have put into and received from the interaction.

The PROJIMO approach: Informal organization and team management

We who work at PROJIMO are in no position to speak with authority about 'organization and management'. Sometimes we wonder if our achievements are due more to our disorganization. Whatever organization and management we have is informal and more or less cooperative. Not only are there no clear-cut divisions between 'managers' and 'workers', but even the division between 'workers'and 'patients' is unclear. (In fact, we avoid words like 'patient' and 'client'.) Parents, children, visitors, and everyone else are invited and expected to help out in whatever way they can. Most members of the PROJIMO team are disabled young persons who first came for rehabilitation or aids. They began to help out as best they could, and finally decided to stay to learn and work. Some stay a few weeks or months, learn new skills, gain confidence, and then go on to something else. Others stay for years. Some come and go, and return again.

PROJIMO is like a big family, mainly of young people, growing up together. Most of the work team is made up of young persons who are themselves benefiting from rehabilitation, learning to work, and learning to relate to each other. It would be a mistake to use the same goals and measure of 'production efficiency' as you would for a shop that employs already trained and experienced workers. There is no boss to give orders. Yet the needs of the disabled children place a demand on the group to work relatively hard, and to accomplish what they can. Hours are flexible. There are quiet afternoons where half the workers suddenly decide to go swimming in the river. And there are busy days when several team members work until midnight to finish a brace or limb or wheelchair for a family that needs to return home on the morning bus. They choose to work overtime, not because someone tells them to, or because they get extra pay, but because a child's father explains that he cannot afford to miss another day's work or a mother is worried about a sick child she left at home.

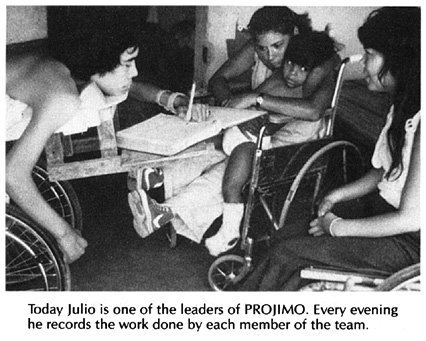

When a situation arises that will require extra work and responsibility, the group as a whole decides if they think they can handle it. For example, one time a teenage boy named Julio arrived who was almost completely paralyzed(quadriplegic). He had severe pressure sores, and was totally dependent for all his daily needs. The team, which had no one specially trained in nursing care, met and discussed whether they could accept Julio in PROJIMO, since no family member was prepared to stay with him. Some argued against accepting him. Others argued in favor, pointing out that his home situation was miserable. (His stepfather resented his mother spending time with the boy.) At last the majority decided to accept Julio, even though a few team members said that they would not be willing to help in his care. It turned out, however, that some of those who had at first been unwilling became those who spent the most time with Julio. Not only did the group do an excellent job in healing his pressure sores and tending his personal needs, they became his close friends.

The team invited Julio to take part in evaluating the needs of other disabled children, so that he could learn history-taking and advisory skills. They also gave him the job of chief 'work checker'. His job was to keep a list of the various jobs that needed to be done each day and who was responsible for doing them. He would check to see that the jobs were getting done and speak to those who needed reminding. Since he could not get around easily, the group agreed that when Julio asked anyone to send someone to him, he or she would do so. Thus Julio, as the most severely disabled team member, was given the most power in terms of program management. This is in agreement with the politics of the program, that only through a just redistribution of power will the weak and marginalized gain a fair place and voice in our society.

The fact that PROJIMO has no 'boss' creates certain problems while it avoids others. Individual concern, group pressure, children's urgent needs, and parents' appreciation are the main motivations to do a good job. Some team members work much harder than others. When someone is not working enough or other problems arise (such as rudeness to families) the group meets with the person. In extreme cases the person may be asked to meet the group's expectations or to leave. So far, however, those who have left have done so by their own choice.

Different team members are able to work at different speeds and effectiveness, depending on their disabilities. Therefore, the group judges a person's work not by how much he produces, but by whether or not he is doing the best he can. A person who works responsibly gets higher pay, even if unable to work fast. Within the limitations of money available, the group decides how much different team members will receive. New team members who are learning work habits and skills begin as volunteers, with only their room and food paid. Later, they earn more, depending on how responsibly and steadily they work. The group decides.

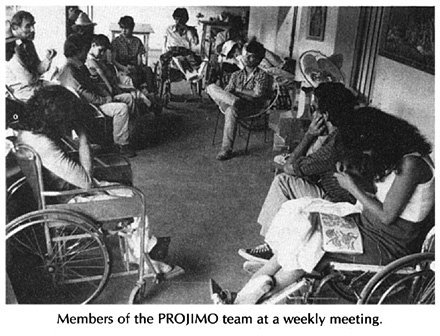

The team meets regularly to plan activities and to decide who will take responsibility for what jobs. Different persons take charge of different aspects of the program: consultations, record keeping, accounting and different shop activities, such as aids making or wheelchair making. Playground maintenance, housekeeping, cooking and clean-up is usually done by turns. One person keeps track of the hours worked each day by different participants and this is used as a guide for monthly wages.

This whole organizational approach is informal and loosely structured. It is a process of ongoing experimentation and change. In short, a group of people are learning how to work and live together as equals. Sometimes things seem to work out better than others. It is the adventure of it all that keeps everyone going -the challenge to create a friendlier and fairer social order, if at first within only a small group.

EVALUATION

An ongoing process of evaluation by the members of a community program is necessary if problems are to be corrected and improvements made.

| Evaluation is a tool for problem-solving and planning. |

Informal evaluation can take place often: the group sits down together once a week (or even for a few minutes once a day) to discuss successes and failures, what seems to be working well, and what does not. Together the group looks for solutions and makes plans.

A somewhat more formal evaluation might be done at the end of each month and each year.

. The PROJIMO team, at the end of each month, makes an effort to fill out an evaluation form that outlines the following information:

| numbers and names of workers involved, the responsibilities of each, hours worked, and pay received | |

| number of children seen (new and returning) at the center and

in their homes. Also their ages, type of primary disability, and secondary disabilities. | |

| number of children who stayed at PROJIMO for more than one day, for how long, and with what family members | |

| attention received by children and families: hours of instruction or therapy, number of braces, limbs, wheelchairs, and other aids or equipment made or provided | |

| accounting for costs of the above, including what portion was paid by each family and how much was paid by the auxiliary fund (See Page 484.) | |

| summary of financial accounts with lists of all monies gained and spent | |

| summary of evaluations of individual children by the PROJIMO team and by their parents (This includes a list of children who have made return visits, with comments on their progress and response to suggestions, home therapy, or aids.) | |

| volunteer help or participation by members of the community (children and adults) | |

| number and profession of 'special visitors' or visiting instructors | |

| new relations or interactions with other rehabilitation centers, programs, and communities | |

| feedback based on parent questionnaires, what they and their children have gained from PROJIMO, how they feel they were treated, what criticisms they have, and suggestions for improvement | |

| outstanding problems and successes in each of the main activities of PROJIMO | |

| conclusions and recommendations |

To help in the evaluation of PROJIMO, parent questionnaires are given to each family at the end of their first visit. Another questionnaire is sent several months later, to learn more about how the child has (or has not) benefited.

The PROJIMO workers are still not happy with the forms and questionnaires they are using, and have revised them several times. For this reason, we do not include samples here. However, we would be glad to send our forms, such as they are, to anyone who thinks they might help in designing their own.

In addition to the monthly written evaluation, at the end of each year the PROJIMO team has an 'evaluation dinner'. The team invites some disabled children, their parents, and some members of the community to participate. The activities of the past year are reviewed, along with problems and successes. The long-range 'vision' and direction of PROJIMO is discussed. Based on this discussion, plans, changes, new activities, and goals are outlined for the coming year.

When families first arrive at PROJIMO, they are given a leaflet which describes the program. It describes or lists:

| the reason for the program | |

| who the workers are | |

| how the family can help (work that can be done) | |

| suggestions for donations such as blankets, wood, rope, food | |

| the services provided | |

| the disabilities that are attended |

This is the way the leaflet starts:

WELCOME TO PROJIMO

Most of us who work in PROJIMO are disabled villagers. We understand the difficulties disabled children face in our society, just as we understand how hard it is for many families to find adequate rehabilitation counseling and services. Orthopedic aids as well as physical therapy are very expensive. The few free services that do exist reach only a small fraction of the children who need them. Therefore, many disabled children, especially in rural areas lack even basic rehabilitation services. We formed PROJIMO to provide friendly advice, therapy and orthopedic aids to disabled children whose families could not obtain, for economic or other reasons, the services that their children need. Family members as rehabilitation workers For most disabled children, we believe that the best place for rehabilitation is in the home, and that the best 'therapists' are those who most love and understand the child: the members of his or her own family. Our goal in PROJIMO is to help you, the parents and relatives, to provide the best rehabilitation and opportunities you can for your child. Here in PROJIMO we live together as a family. We invite you and your child to participate in our work and activities. We ask you for your suggestions and opinions. We appreciate your assistance with exercises or making aids for your child (or other children), as well as your help in the daily maintenance and work of PROJIMO. PLEASE HELP US TO HELP OTHERS |

FINANCING

The myth of self -sufficiency

It is a goal of many community programs to become as financially self-sufficient as possible. Only when a program does not depend on outside funding, can the community and participants of the program have a full sense that 'The program is ours. We run it. We control it. We make the main decisions ourselves."

Realistically, however, for health programs in general and for rehabilitation programs in particular, economic self-sufficiency is difficult to accomplish. This is especially true if the program aims to serve mainly those who are poorest and whose needs are greatest. The poor earn barely enough to feed and clothe their children, and then sometimes not adequately. The additional expenses of trying to meet the needs of a disabled child may be too much for the poor family to bear, even when the costs are kept low.

| The biggest obstacle to economic self-sufficiency of any community program is poverty. |

In a country where social injustice causes widespread poverty. it is not fair to expect the poor to pay for more than a small part of the cost of rehabilitation services or aids. Nor is it fair to ask a busy rehabilitation team to try to make their program self-sufficient through separate 'income- producing activities'. (However, 'income-producing activities' can help meet some expenses and prepare disabled persons to work and earn independently. We discuss this on the next page.)

True self-sufficiency of a community service program may only be possible through a process of social change and fairer distribution within the whole structure of the society. Only when enough jobs are available and nearly every family earns enough to be self-sufficient in terms of meeting its basic needs, can program self-sufficiency become a realistic goal. In the meantime, some sort of outside funding, government or private, is usually necessary.

Funding - government or non-government?

Ideally, governments should help meet the costs of people-centered community-run service programs. Unfortunately, government funding often brings with it a high degree of outside control, including pre-defined (often disabling) limitations regarding local planning and how much community workers are taught or permitted to do. The disabled and their families tend to become the objects of program objectives, to be worked upon, rather than the leaders in their own struggle for dignity and self-reliance.

Also, it is usually difficult for a local village or community group to ask for and obtain funding from the government. The red tape, 'preliminary investigations', restrictions, and delays are often endless. More promises are made than are kept. Thus to speak of a government-financed community-oriented program usually makes little sense.*

*One exception to this is the ORD (Organization of Disabled Revolutionaries) in Nicaragua, a non-government, people-centered program for which the Sandinista government has set up a red-tape-free 'auxiliary fund' to help poor families meet costs (see next page). Such restriction-free aid may only be possible in countries where popular governments have a strong political will to serve the people fairly.

NON-GOVERNMENT FUNDING

This can come from a variety of sources, including volunteer agencies, charitable foundations, and religious charities. To permit greater independence, it is a good idea to have several sources of funding. (Some government assistance may possibly be included without sacrificing community control, if the amount is relatively small.)

In Pakistan, a religious (Islamic) law each year takes two and a half percent of the money people have in banks, to be used by local committees for the benefit of widows, orphans, and disabled persons. Since this law was passed in 1981, it has become a growing source of support for community rehabilitation centers.

LOCAL FUNDING

It is also a good idea that a fair part of program costs-if possible at least half-be met within the community. Possible local sources for meeting costs include:

| Fees or contributions from families served: Some families will be able to pay more than others. Therefore, the fee should depend on their ability to pay. When families come from outside the community, their ability to pay may be hard to judge. Project PROJIMO has tried an 'honor system' for payment of services. They ask the family to make whatever donation they can afford. So as not to shame the family who gives little, or make proud the family who gives more, each family puts whatever they can in a closed box in the corner. Only the family knows how much they gave. |

| Service 'in kind' or with work: The community's contribution does not have to be in money. People can donate materials (sand and rock for building), do volunteer work, or provide food and lodging. All this reduces program costs. |

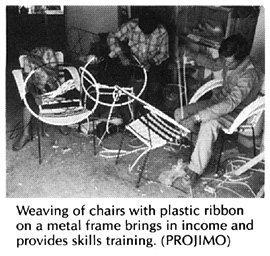

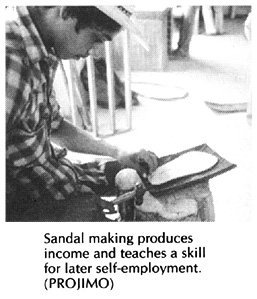

| Income-producing activities: Production of things for sale is another way to help meet program costs. It also provides skills training for older children and temporary workers in the program. We will discuss this further on Page 509. |

Although production of items for sale may not bring in much money, the extra income may mean that more disabled persons can be employed on the program staff. They can learn rehabilitation skills and at the same time learn income-producing skills, both of which they may put to good use then they return to their own village.

Some programs that are run for and by disabled persons have succeeded in meeting a large part of their costs through production and sale of goods. For example, the Centre for the Rehabilitation of the Paralysed in Bangladesh creates a wide range of orthopedic and hospital equipment, much of which they sell to orthopedic hospitals. (See Page 518.) The Disabled Revolutionaries of Nicaragua has succeeded in developing a nearly profitable business out of making low-cost, rough-terrain wheelchairs. (See Page 519.) In Paraguay, a group of disabled workers has also made wheelchair making a small but profitable business.

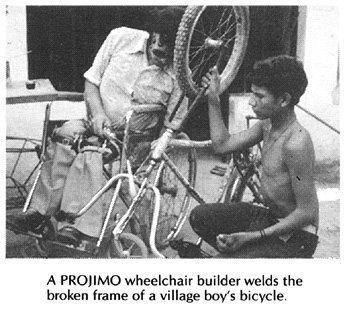

| Repair services: In addition to producing items for sale, a team of disabled village rehabilitation workers can provide a wide variety of repair services, The PROJIMO team in Mexico repairs plows, welds broken machinery and tools, repairs bicycles, solders holes in buckets and car radiators, re-soles boots and sandals, and sharpens axes. (They have even repaired broken plaster saints from the church!) All these services they provide using the same skills and equipment that they use in making wheelchairs and rehabilitation aids. No one else in the village provides these skilled repair services. They have therefore done a lot to increase the villagers' respect and appreciation for disabled persons in the community. |

| An 'auxiliary fund' to help poor families pay for aids and services: As we have discussed, many families cannot pay for the services or aids their child needs, even though a community program provides these at low cost. Some kind of economic assistance is needed if the disabled child's needs are to be adequately met. |

To provide such assistance, PROJIMO has arranged for an 'auxiliary fund' provided by outside donors. The fund, which is kept in a separate bank account, pays to PROJIMO the difference between what a poor family pays and the actual cost of aids or services received. Thus the workers get full payment for the services and aids they provide. In effect, the fund aids poor families, not the program directly. This allows the team to have a better measure of its accomplishments. If the team works efficiently and gains the necessary management skills, in time the program should need no more direct outside funding. The payments from the auxiliary fund, together with whatever families are able to give, should cover the cost of wages, supplies and maintenance. This will mean that the program has in a sense become self-sufficient- even though poor families still need financial aid. Project PROJIMO began to approach self-sufficiency on these terms in its third year.

An argument can be made for trying to obtain government financing for the 'auxiliary fund'. (This is in fact being done in Nicaragua. See footnote on Page 482.) The fund could even be managed by a local official (if honest) or another administrator outside the rehabilitation program. At the end of each month, the team could give the administrator an accounting of the services and aids provided, their calculated value, and the amount paid by families, with receipts. Payment would be made, as if by contract.

Below is a form that can be used for keeping records for money to be paid by the auxiliary fund (adapted from Project PROJIMO).